If all politics is local, perhaps all history is personal.

“If we’re going to make progress, we have to understand history: To move forward you have to look back,” said author and Humanities Washington speaker Clyde Ford.

“You have to make sure history doesn’t repeat itself, and too often, in too many places in high-tech right now I see history repeating itself in terms of the negative impacts of technology on human rights, on race relations. I’d like to do something, and I think my dad would really support doing something, that would allow that to change. And the first place is to understand where we’ve come from.”

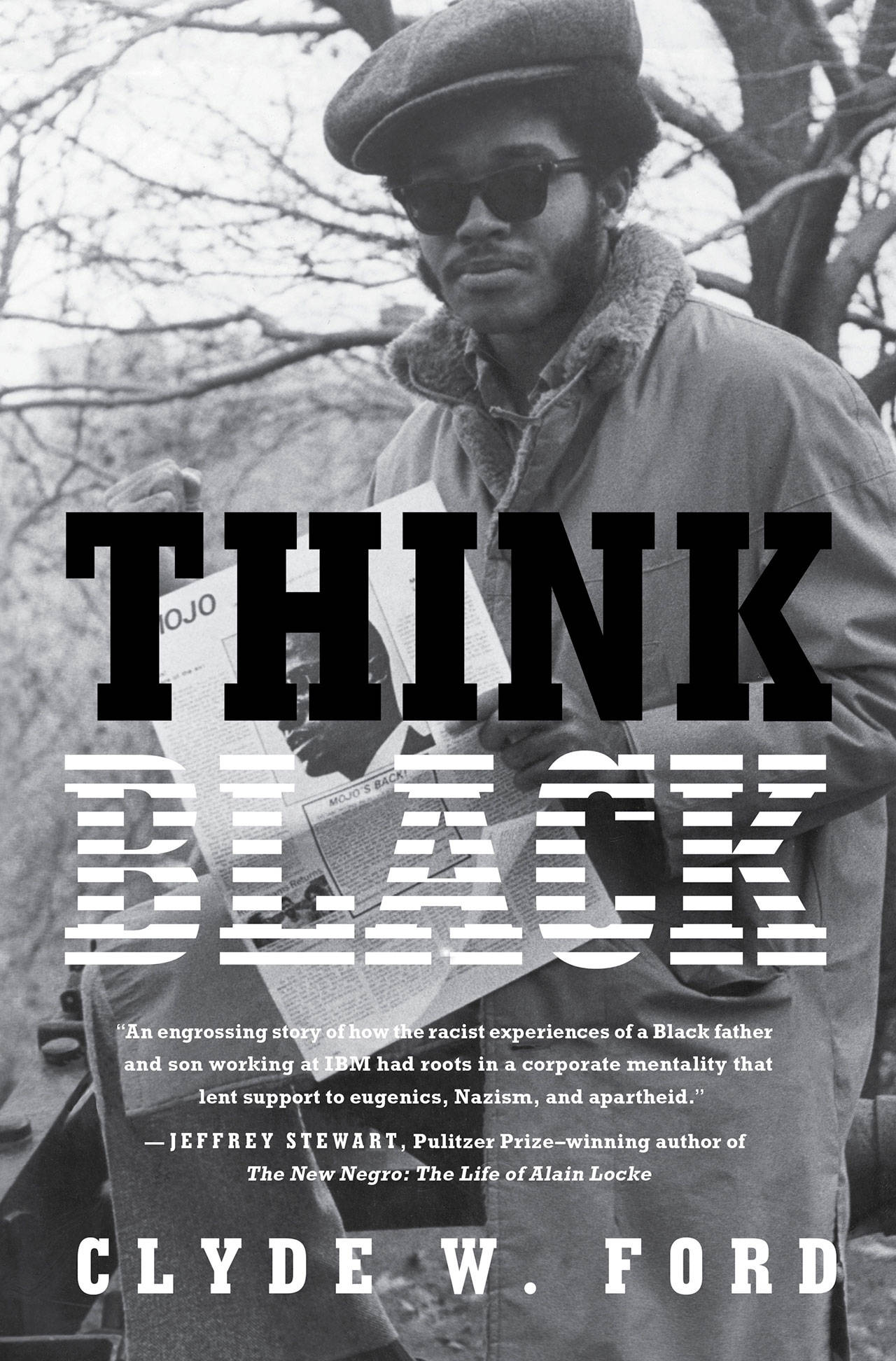

The “we” in question takes several forms as Ford follows his own advice in a new memoir “Think Black” (available now in print and digital versions); a frank and poignant story of family, progress, technology, racism and corporate secrets that stretches from today’s hashtag-headlines to the dawn of the digital age.

Ford’s father, John Stanley Ford, was the first African American software engineer at IBM in 1947, hand-picked personally by firebrand tech tycoon Thomas J. Watson. The author eventually followed suit and became one of the company’s very few black employees some 20 years later. In the past, IBM’s white employees had refused to accept a black colleague and did everything in their power to humiliate, subvert, and undermine the elder Ford.

And, years later, remarkably little had changed.

Though Ford’s father refused to quit, and was instrumental in the development of what was arguably the first true computer, the ultimate psychological cost of his finally internalizing much of the racism he encountered at IBM created a rift between he and his modern, progressive son that was at times tumultuous and would, decades later, lead the younger man on a mission of discovery that took him to dark places both personal and global.

Ford will visit the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art at 7 p.m. Wednesday, Sept. 25 to discuss the book, the experiences of both his father and himself while working at IBM, and many facts that company would rather you not know.

Admission is free, though reservations are recommended. Visit the “events” section of www.biartmuseum.org to secure tickets.

It’s a very different sort of book for Ford, the author of 13 works of fiction and non-fiction, also a psychotherapist and accomplished mythologist. And he said he began it with a likewise very different idea of the sort of story it was (he envisioned something of a “Hidden Figures”-type of tale initially), but quickly found himself in unfamiliar, more treacherous waters.

Maybe it wasn’t worth the struggle?

“I never thought that,” Ford said.

“But I can certainly say there were times in which I was writing this book and I thought it would be a little bit more of a ‘feel good’ book and it turned out to be something less than that. There were times, particularly when I was doing the research about IBM’s involvement in human rights abuses starting in the ’20s and continuing right to this very day, that really it was hard writing.

“There were times during that research that I was either in tears or I was dry heaving because I was disgusted by what I read and by the notion and the knowledge that both my father and me worked for a company that had involvement in the Holocaust, apartheid, and facial recognition as it’s used to determine race.”

The elder Ford, who passed away about 20 years ago, could not have known that his hiring was meant to distract from IBM’s dubious business practices, including its involvement in the Holocaust, eugenics, and apartheid, but it quickly became a central facet of his son’s new book — and one a surprisingly large number of readers were apparently unaware of.

“I think most people don’t know or they have some vague knowledge and they just don’t want to acknowledge because we use technology today in a way that we just want to think that it’s all good. And the truth is the history of technology and its use is not all good; there really is a dark past,” Ford said.

“I was called out of the blue … by Edwin Black, who wrote the book ‘IBM and the Holocaust.’ Really, I used that book as the main source of my documentation, so we had a wonderful conversation and Edwin … said, ‘Look, everything I’ve written in that book I’ve got in a file cabinet, 35 file cabinets. Everything is documented. If anybody questions you about any aspect of IBM’s involvement in the Holocaust, you send them my way and I will give them as much source documentation as they want.’

“So while I felt really good about the source information that was available and what I referenced in the book, it was not easy to learn that IBM was involved in eugenics, with Hitler, in South Africa, and also just up to the present day; 2018 was the last referenced source I had and that was only because the book had to stop there because we needed to get to publication. But just last week there was other information that had come out about that.”

Perhaps it isn’t shocking then that the company Ford had dedicated so much of his professional life to was less than supportive when he came calling for his and his father’s personnel records.

“I was at first a little surprised because I started the book with a different point of view,” Ford said. “I thought IBM would love a story about two generations of IBM employees and be very forthcoming with the information. It turns out IBM wasn’t, and I understand now why. And I think that’s because there’s something there they feel a little better about not revealing in a very public way.

“There are many things, particularly regarding technology, that we just don’t want to talk about and I think we need to because if we don’t talk about them they keep appearing again and again and again,” he added. “Amazon is the latest instance of where, you see this idea that technology is all good but when it’s applied, for example, to folks trying to get into this country, fleeing human rights abuses in their country, and facial recognition is used to discriminate — it’s not all good. And I wanted to make sure we have this conversation so we understand the technology that we’re using, the history of that technology and really can have a good discussion about how we want to use that technology today.”

In a particularly powerful moment early in “Think Black,” Ford’s father, sometime in 1957, brings home components of the machine he’s working, the legendary IBM 407, and shows his son and young daughter how they work.

“Computers will control your life one day,” he says. “Better if you learn how to control them first.”

The elder Ford clearly understood the potential of what he was developing, but could even he imagine the world of today and our reliance on the systems it would inspire?

Ford says no, probably not, and has a pretty respectable case study to reference.

“I was flying back East on part of my book tour early on and I happened to sit next to a woman … who herself is a really famous author,” he said. “And [she] said to me, ‘Oh, I can’t believe it. My dad worked for IBM at the same time your dad did.’ And she said that toward the end of his life [they] were walking down the street and he asked [her] what are all those people doing with their heads down looking at those little things. He apparently didn’t really understand cell phones. She told him exactly what they were doing. He looked at her and said, ‘Oh my God, we released a monster.’ I think there couldn’t have been a more appropriate response.

“I think it was that my dad and his IBM brethren like that man … did not fully grasp what they were releasing and what they were developing,” he added. “And if they were to see it now, I believe they would have the same response.”

Thus an insistence on responsible tech usage is one of the main ideas Ford hopes people take from “Think Black.”

“It’s up to us to determine what we want to do with that monster,” he said. “We’re not going to put it back the box; that’s pretty obvious. But I do think we need to be more literate about how we use the technology. Technology companies need to be a lot more conscious about releasing bias-free code. There are so many things … that I think we need to do, that we’re obligated to do, to be responsible users of this technology.”

In speculating as to what his father might say about the American political and social climate of 2019, Ford finds little to laud.

“My father was a little bit conservative in that he really believed a lot that the government was doing the right thing,” the author said. “I think it would be a challenge for him to see some of the things that are going on right now, particularly with the way technology is being used to discriminate; technology is being used in terms of facial recognition. And I think what would really bug him a lot is that African Americans and people of color are on the wrong end of that technology.

“Facial recognition, for example, it’s biased against people with dark skin. Even down to, and this really surprised me, you go into a restroom, let’s say, and you’re trying to get the water that’s on an automatic system to run, and because your skin has a different reflectance color you can’t get the water to turn on when you need to wash your hands. That’s technology that’s just not equipped to handle the kind of society that we live in and I think my dad would have a problem with that, as he had a problem with not as many African Americans and people of color working for IBM as he’d hoped there would be.”

It’s a carryover of inherent biases that has always existed, Ford said. Even the seemingly benevolent trend of the late ‘40s that saw powerful men like IBM’s founder and Major League Baseball’s Branch Rickey, who shattered historical taboos by hiring Jackie Robinson at about the same time as Ford’s father was brought aboard at IBM, personally seeking out young black men to employ was clearly not coming from a sense of altruism if you look closely enough.

“I think there were a number of factors going on,” he said.

“One is that you had a generation of African Americans who had put their lives on the line in faraway places, some of them had died fighting for rights that when they got back to the United States they didn’t have for themselves. The instances, for example, of men, veterans from World War II in uniform, being lynched in the South is just horrible. It’s a horrible history that I don’t think we’ve come to terms with.

“And then you have a different set of pressures with that was going on with some of these companies,” he added. “Now, I thought both in Major League Baseball and also in high-tech there was this sense of powerful men reaching down from above — turns out that’s not really the case.

“All of their motives were not altruist; there were ulterior motives going on there. In baseball, for instance, Branch Rickey was pushed. He did not just decide out of the goodness of his heart to hire Jackie Robinson. He was pushed for political and financial reasons. And as I really understood that story a little better I thought, ‘Well, it will be interesting to know the forces that were acting on Watson.’

“I think Watson and IBM, but particularly Watson, was pushing to make sure that people didn’t look too deeply into IBM’s recent past in the post-war era, so it would be better to focus on hiring African Americans, hiring Jews, than to look into IBM’s involvement with, let’s say, the Third Reich and the Holocaust.”

Ultimately, though, it’s hard to hate completely whatever factors went into opening doors for people of color, however too few the cases may have then been (and to some extent still are) who were allowed to step through them.

And the world of today offers few signs of marked improvement. Having examined his father’s experiences and re-examined his own, and in considering the state of current race relations in America, Ford says he has hope — but very little optimism.

“I want to distinguish between hope and optimism; I think the two are a little bit different,” Ford said. “Am I optimistic? Eh, I’m not sure. Do I have hope? Absolutely, I couldn’t live if I didn’t have hope.

“Every time I hear another story of young black man being killed, often by law enforcement, it really hurts me and I wonder have we made the progress? When I read, for example, the Kerner Commission’s 50th anniversary report on whether there’s been progress made on race relations in the last 50 years … it’s really hard to be optimistic. So in many respects I can’t say I’m optimistic. But I am hopeful.”