▼ Noted photographer John Wimberley will visit Bainbridge for a weekend workshop.

John Wimberley didn’t begin his working life as a photographer, but he wonders whether he might have been one in a past life.

It was during a stint as an electronics technician in the U.S. Navy in 1966 that Wimberley happened to buy his first camera.

He wore it out in three months and had to buy a new one.

“It was the feeling that it was the absolutely right thing for me to be doing,” he said. “It was such a deep feeling of rightness that it was hard for me to conceive of dong anything else.”

The photographer, renowned for his rich black-and-white landscapes, will visit the island this weekend from his Oregon home to share his knowledge in a hands-on workshop at the Creativity Center.

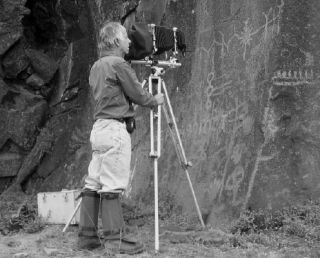

After mastering that first camera, Wimberley moved on to more complex machines, notably a large view camera, the type that old-school landscape photographers often use. Most photographers agree that it’s a difficult piece of equipment to master – but Wimberley already knew how to use it, too. Just as he intuitively understood how to experiment with his developing chemicals to improve his black-and-white prints.

So while the technical aspects of Wimberley’s trade may have contributed to his initial comfort with the camera, that feeling of ease quickly evolved into something deeper, a sense that he was “simply remembering.” And that was what led him to consider the possibility of reincarnation.

On Wimberley’s Web site, photographer Georgette Freeman notes, “…one needs to know that John Wimberley is an animist: someone who believes that natural phenomena and objects, as rocks, trees, clouds, etc., are alive and have being.”

Wimberley responds that when he started shooting, “I didn’t have any such ideas.”

What he does remember is that over the years, as he spent increasing amounts of time in nature, he began paying attention to what was going on around him with all his senses.

“I came to feel that everything around me had life in it, including those things that we think of as dead,” he said.

Although his photographic life developed, Wimberley had to continue his day job, which he did until January of 1981, shooting in the evenings, during lunch breaks, and any other time he had off.

“I literally had no social life,” he said.

One morning, he woke up and he’d had it. He quit his job and promised himself never to do work again that didn’t come from his heart. Although he nearly had a panic attack the first morning of his official stint as an unemployed photographer, he eventually settled into the idea that having time but no money was still preferable to the alternative.

“By some absolute miracle, I still have a roof over my head,” he said. “It’s really been astonishing because at the time, I wasn’t known, and I started working from print sales. And I still am. And I’m very glad I made that decision because otherwise, I might have withered up and died or something.”

Wimberley says he’s never once experienced artistic malaise; his transitions tend to come in the form of subject matter. For a period of six months, he focused on a woman underwater. The brief exploration resulted in one of his best known works, “Descending Angel,” which in its rich, textured contrast, indeed resembles a heavenly body making her way steadily down to earth, literal and metaphysical gravity rippling from her.

Wimberley says that many viewers tell him his work conjures up divine themes – angels, spirits, holy ghosts on rock formations. These last Wimberley has sought out in the Mojave and the arid climes of Eastern Oregon among other places, seeking out Native American rock art.

He believes this outer manifestation in the work itself comes as a direct result of his inner practices as he’s in the middle of photographing, for instance during his solo trips to the desert.

“Those trips are very intense meditation,” he said. “When one reaches wholeness, it inevitably touches spirt. And that comes through in the picture.”

In this weekend’s workshop, Wimberley plans to present to students what he calls a “very alternative view of how to make photographs, in terms of what’s going on behind the camera.” The approach is based not only on paying attention to what the photographer sees through the view finder, but what he or she discovers inside – feelings, cues, and clues that can guide the shot. Then, perhaps, the artist will experience transcendence.

“Because if you’re paying attention inside, you’re feeling your feelings, and you’re feeling your bodily reactions – it does show up in the photographs and it does add richness,” he said. “Because you’re not just photographing from your head.”