As winter comes to an end, the island’s bare branches might appear lifeless – but if you look closer, you’ll find them covered in buds just waiting to burst.

You might make that same conclusion looking at the site of the future Bainbridge Island Museum of Art.

Its gray foundation mirrors winter’s bleak skies, but like the tulips and daffodils, a lot is going on below the surface. Literally.

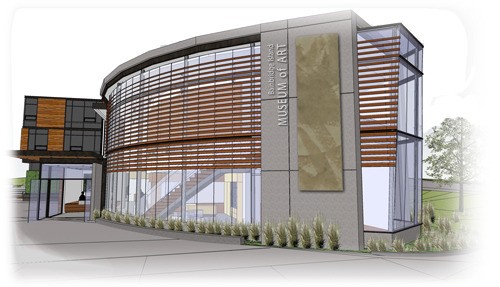

The museum, aiming for environmentally friendly LEED gold designation, took a detour to incorporate geothermal heating, digging 14 underground wells that will draw heat from the earth. That’s in addition to plans for solar panels on the roof; use of recycled materials, including insulation made from old denim; a vegetated roof garden and a “living” wall. The building, designed by Bainbridge resident and architect Matthew Coates with input from the community, would be the first museum in Washington state and one of only a handful in the country to earn that designation.

“It’s not easy for museums to qualify because they have a high energy need – to keep the temperature and humidity constant for the art, along with high lighting requirements,” Coates said.

And while Coates contemplates possible gold status,

BIMA’s Executive Director Greg Robinson is pretty excited about the basement.

“It’s not a space that a lot of people think about,” he said. “It’s not the sexiest part.”

It’s important to Robinson because it contains the museum’s archival space for art storage, a loading dock, offices and the mechanical rooms. In other words, it’s the guts of the museum, and essential to behind-the-scenes magic. Attention was paid to meet the highest museum standards to be eligible to host exhibits from other museums in the region.

Above ground, Phase I includes the 95-seat auditorium which has already been used for plays, documentary screenings and civic events, and classroom space which hosted numerous KiDiMu summer camps last year, as well as an ongoing Life Drawing class on Tuesdays.

Learning curve

The building’s curve will lead visitors toward the entrance, and the generous use of glass allows people to see into the museum.

“We wanted it to be accessible, approachable, inviting,” Coates said. “Not just a box with cool stuff in it.”

“Sherry Grover taught me about public spaces,” said Cynthia Sears, the museum’s initiator. “People want to know they’re not going to be trapped; they want to know how something works, that they can move at their own pace and won’t get stuck with someone lecturing them.”

Once inside the lobby and reception area, an adjacent orientation gallery will enable docents and teachers to orient small groups and relay “museum manners” before setting off on an aesthetic adventure. That area spills out into the permanent collection gallery and an adjacent children’s and youth-focused space that might house art by kids – or art that is of interest to them.

Around the corner is a small gift shop that will carry touchstones, not trinkets.

From there, the Grand Hall leads to a dramatic staircase that ascends along the building’s curved wall of windows.

The top floor will house revolving exhibits in the main gallery and in the intimate spaces of the Sherry Grover Room and the Beacon Gallery, named for its visibility to those traveling by ferry.

A 300-square-foot roof terrace and garden overlooking the courtyard has been named in honor of Island Treasures and early museum supporters George Little and David Lewis.

An elevator (or stairs) will take visitors to the small cafe or back to the lobby.

The overall size is ample but not intimidating and natural light, greenery and natural materials will add warmth to the space as well.

A beacon

From the beginning, the project has been charmed, not only in landing such a fortuitous location, but in drawing a team of talented, gracious people.

Board member and engineer Ralph Spillenger, formerly in charge of NASA facilities, has been instrumental in shaving $1 million off building costs, said Sears. “He checks everything. And he’s one of the nicest human beings I’ve ever met.”

Coates is so local people forget he’s a nationally acclaimed architect – whose specialty happens to be environmentally progressive buildings.

“It’s been a huge honor to be involved in this project,” he said (repeatedly).

Even one of the building’s design elements metaphorically reflects the magnetic draw the project has had, and will have into the future. When lit, a two-story glass structure facing the corner will act as a beacon, visible from the water and to those pulling in from the ferry.

To learn more, or to get involved, visit www.bainbridgeartmuseum.org.