The federal investigation into the sinking of the historic tugboat “Chickamauga” last October in Eagle Harbor was launched just hours after the vessel sank, according to court documents filed Wednesday.

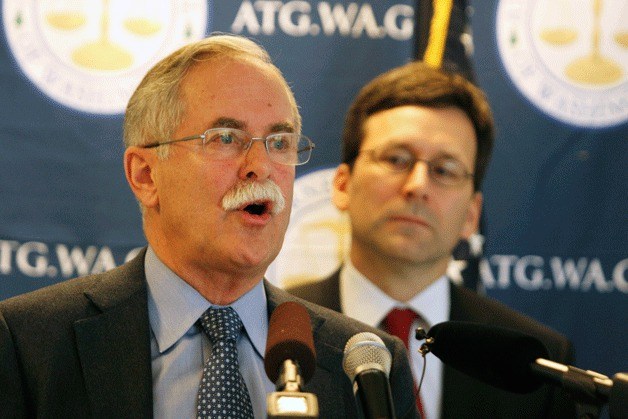

Washington Attorney General Bob Ferguson announced this week the state was filing criminal charges against Anthony R. Smith, the owner of the neglected 100-year-old “Chickamauga,” at a press conference Wednesday in Seattle. Authorities allege that Smith abandoned the old tugboat at its mooring in Eagle Harbor Marina and is responsible for the pollution that spilled out into Puget Sound — roughly 200 to 300 gallons of diesel fuel.

Smith has also been charged with first-degree theft because he never paid more than $8,500 in moorage and other fees to Eagle Harbor Marina for keeping the tugboat at the marina.

Court documents show that a special agent with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency immediately began to look into the sinking of the “Chickamauga” in the hours after it sank to the bottom of Eagle Harbor while still sitting in its slip.

Special Agent Jeffrey Hayes first contacted Doug Crow, the harbormaster at Eagle Harbor Marina who had actually been a liveaboard in his own vessel moored right next to the “Chickamauga” from February through September 2013.

Crow told the agent that Smith, the owner of the 70-foot tugboat, had piloted the vessel to the marina and left it there sometime around February 2013, and that Smith had not been seen again since shortly after he brought the aging tug to Eagle Harbor.

Authorities said Smith paid the first and last month of moorage fees for the “Chickamauga,” but paid nothing more despite being contacted four times in March and April last year.

Crow also told the investigator that a woman came by the marina last April to pay Smith’s moorage fees, but gave him a check that was rejected by the bank due to insufficient funds.

Court documents indicate that the federal agent came to Bainbridge the same day of the tug’s sinking to continue the investigation, and noted the pollution that had escaped into Puget Sound, the strong smell of diesel fuel in the air, and the rainbow sheen that the fuel had left on the surface of Eagle Harbor.

Later that day, the Coast Guard and Ecology officials spoke with Smith on the telephone, and he allegedly told them he was working in the fishing industry in Squaw Harbor, Alaska.

Hayes first spoke to Smith on Oct. 21, when he received a call from Smith who claimed he was in Sand Point, Alaska.

Smith said he failed to pay the $8,560 in moorage fees because a company did not pay him money that he was owed. Smith told Hayes that he was forced to file a lawsuit against the company when he almost went bankrupt.

Ten days later, Hayes contacted James Hicks of Aqua Dive Services. Apparently Hicks had received a call from Smith asking for help.

Smith told Hicks, “Please help me. I can’t afford to pay Global (Diving),” according to court documents.

Hicks did not make a formal arrangement or agreement to get help with the “Chickamauga,” though Smith added that money would not be a problem if such an agreement was made.

Smith continued to tell Hicks he had made arrangements with a man who was supposed to have been keeping an eye on the boat and paying the monthly moorage fees to Eagle Harbor Marina.

Hayes spoke with Smith a second time on Nov. 5 where he elaborated on the supposed caretaker.

Smith said that he had a retired friend named “Skip” check the condition of the “Chickamauga” on a weekly basis. Smith claimed that Skip visited the marina after the boat sank.

The day before the boat sank, Smith continued, someone on the dock told Skip the boat was “sitting heavy in the water” and that someone had reported its condition to the harbormaster.

Before Smith finished the telephone call with Hayes, he said he would send contact information for Skip.

Smith never sent the information.

Authorities later found that Smith was listed as the owner of the “Chickamauga” on his moorage rental application, and had listed the emergency contact person as Victor H. “Skip” Suttmeier of Kirkland.

The federal agent interviewed Suttmeier at his home on Nov. 19, and Suttmeier said he received a call from someone at the Eagle Harbor Marina the day the tugboat sank, but said he didn’t know the vessel had been moved to a marina on Bainbridge Island from its previous mooring at Commercial Marine in Seattle.

Suttmeier also said he never checked on the tugboat when it was moored on Bainbridge, and added that Smith told him after the tugboat sank that it had been sold and belonged to someone else. Suttmeier also said that Smith told him “that everything had been taken care of with the ‘Chickamauga’ and that the new owner of the vessel was in jail,” according to court documents.

Records on file with the state show that Smith bought the “Chickamauga” in October 2009 for $1,000 from a Shoreline man.

The investigator also found the harbormaster at Eagle Harbor Marina had tried to repeatedly contact Smith about the tugboat via email, but Smith never responded. Eagle Harbor Marina estimates that Smith owes $8,560 in moorage and utility fees.

State officials said criminal charges would be filed this week in Kitsap County Superior Court.

Criminal charges were also announced Wednesday against the owner of the “Helena Star,” a 167-foot vessel that sank in January 2013 in the Hylebos Waterway in Tacoma and took another vessel, the “Golden West,” with it. The owner of the “Helena Star” has also been charged with causing a vessel to become abandoned or derelict and for discharging pollution into state waters.

Ferguson, Washington’s attorney general, said the state relied on the federal government to help with the case because the state does not have original jurisdiction in the sinking of the “Chickamauga.”

“We believe that these are the first criminal prosecution of derelict vessels at the state level,” Ferguson said.

“We want to send a clear message that if you harm our environment in Washington state, we will hold you accountable,” he said. “And if we have the ability to prosecute you in a criminal matter, we will do that.”

“That’s going to be a new priority for our office,” Ferguson added.

Ferguson noted the two cases were still in the early stages, and he also thanked Hayes for his work as the lead criminal investigator in the two cases, as well as the EPA Criminal Investigations Division for its recent partnership with the attorney general’s office.

“We really appreciate that cooperation, and it really goes to the theme overall: Which is, in addressing the issue of derelict vessels, it’s going to take a team effort,” Ferguson said. “We need to work with [Commissioner of Public Land] Peter Goldmark; we need to work with the federal government; local prosecutors. The Office of the Attorney General needs to be more involved. We need more resources from the state Legislature.”

Goldmark said local, state and federal agencies need to work as a team to prevent taxpayers from getting stuck with the clean-up bills and environmental damage caused by “the irresponsibility of derelict vessel owners.”

“Today’s work and announcement of these criminal charges is a huge step in the process of holding these owners responsible,” Goldmark said.

Goldmark also noted that the state Department of Natural Resources, working with its partners, had removed more than 500 derelict vessels from state-owned waters.

More assistance from the state was needed for the Derelict Vessel Removal Program, he added.

“It has limited funds and can’t handle the large expensive cases from the ongoing funding – for instance, these two cases today — and additional resources are needed for that,” he said.

In 2011, for example, the sinking of the 400-foot barge “Davy Crockett” in the Columbia River and the clean-up and removal costs totaled $20 million.

“This is a persistent problem,” Goldmark said.

Review writers Cecilia Garza and Luciano Marano contributed to this report.