When the idea of a Bainbridge-Ometepe Sister Island Association first sprouted in Kim Esterberg’s head, he found himself stepping into two worlds.

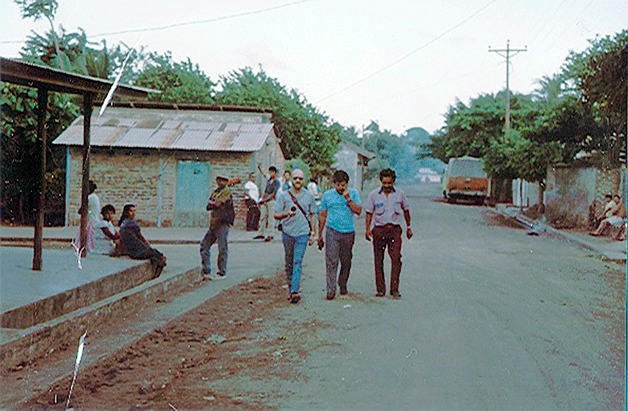

In one, he’s on the tarmac of an El Salvador airport on his way to Nicaragua for the first time.

Surrounding the plane are soldiers armed with AK-47s. It’s 1986, and Nicaragua is in the throes of its own civil war, otherwise known as the Contra War.

In the second, he’s swimming in Lake Nicaragua at twilight off the shore of an isolated Ometepe Island farm with one of the town mayors. Tía Chela is sitting on her porch watching. The fireflies are coming out and the island’s two volcanoes form a silhouette in the backdrop.

“I thought, boy, I can hardly wait to tell the story of this island,” Esterberg recalled thinking about that night in the water.

He encountered both worlds quickly, but they set the theme for what has become a 25-year-long community friendship.

After three years brewing over the idea of a sister island association, Esterberg visited Nicaragua for the first time with the Seattle-Managua Sister City Association — a campaign aimed at forming friendly intergovernmental connections at a time when U.S. policy was to oust Nicaragua’s Marxist government.

An alternative approach

The difference from the sister city association and what Esterberg had in mind, however, was he hoped to bridge Ometepe and Bainbridge in a way that surpassed formal relationships.

“It’s going to be non-political,” Esterberg explained.

“It’s going to be non-religious. It’s going to be simply people on this island at whatever level that are interested in connecting with people on that island at whatever level.”

The trip served as a fact-finding mission for Esterberg. The most he anticipated was more talk with the sister cities office about the potential of a sister island organization. But before he had a chance to get settled in his new surroundings, he was on a crowded ferry crossing Lake Nicaragua to Ometepe where arrangements were made for him to meet its two mayors.

Talk leads to action

A three-day tour of the island — in one of 27 cars in the community — countless introductions and many photos later, Esterberg came home energized and began eagerly spreading the word.

Over the course of another two years, the Bainbridge-Ometepe Sister Island Association (BOSIA) began to take shape.

The year following Esterberg’s first trip to Nicaragua, two Bainbridge filmmakers traveled to Ometepe after making a short film of Bainbridge’s budding enthusiasm for a sister island connection.

Mark Dworkin and Melissa Young rolled a television set down to a park in Altagracia, one of the island’s towns. As they played the movie, Young yelled Spanish translations to passerby, a scene that caught the attention of Padre Juan Cuadra, a priest at the local Catholic church. Later the pair also attended a school bake sale where teachers were trying to raise money to build a new preschool as modest as a thatch hut to protect the children from the sun.

Like Esterberg, Larkin and Young returned to Bainbridge with their story of the priest who supported the sister island connection and the teachers who needed a school.

Two ways to help

While a community of supporters rallied together to raise money for a preschool that would be a better home than a thatch hut, though, two components of what would become BOSIA’s mission were solidified.

First, that the association maintain a community friendship that surpasses political boundaries.

Second, that the association develop a relationship of dignity.

There was a mix of opposition and support for the sister island connection on Bainbridge.

On one hand, there was a Nicaraguan solidarity group on Bainbridge that opposed the Reagan administration’s policy of providing arms for the Contras and getting rid of communists in all of Central America.

On the other hand, there were many people on Bainbridge who were not a bit happy about forming a sister island relationship with a communist country.

“They thought, ‘What gives Kim Esterberg the right to develop a relationship with a communist island in Nicaragua?’” Esterberg recalled.

“But little by little, people just kept coming on board.”

Instead of being against something, like a policy, Esterberg said, the association was an opportunity to be for something positive, like a people-to-people friendship.

Feet on the ground

Feet on the ground

With this in mind, Esterberg returned to Nicaragua in 1988 for the U.S.-Nicaragua sister cities conference in Managua.

A delegation of eight Bainbridge Islanders traveled to the conference with him but eagerly left the conference for Ometepe.

Along with them they brought the funds raised to begin building a new preschool on the island. But having been a year since they spoke to the group of teachers, it was truly going to be a grassroots operation to get the money in the right hands to make the project happen.

The word had spread of a group from the U.S. wanting to connect with Ometepe. It wasn’t a surprise when Nicaraguan military officials required the group to funnel the project money through them.

“We said, we don’t want to,” Esterberg recalled.

“We want to give it to the school. We want to give it to the teachers. It was a real kind of a showdown, and I was a little nervous but they finally got the idea we weren’t going to give up. This was not an organization that was going to operate through the government, regardless of party.

“Then we thought, ‘Well now that we’ve made that stand, who do we actually give the money to?’”

All fingers pointed to Padre Juan Cuadra, the priest in Altagracia.

Locals have their say

From the beginning, Cuadra emphasized the people on Ometepe will have the most respect for a project if it’s their project.

“He was very stingy with the money,” Esterberg said.

“And everybody, for years later, complained ‘Padre Cuadra is a slave driver.’”

Cuadra made sure, though, that the funds were no lavish gift from the North. Regardless of who footed the bill, the community on Ometepe built the school with their own hands.

“It was their own hard work,” Esterberg said.

“Ever since then, it’s been the vision of [BOSIA] to develop a relationship of dignity. And the dignity is only going to happen when we feel that we’re not only doing for, but with, those people.”

This first project set the bar for what has become a give-and-take relationship.

A healing path

Not long after building the preschool, BOSIA began selling coffee on Bainbridge from a Ometepe co-op — an operation that began with luggage bags to side-step the U.S.-Nicaragua trade embargo at the time. With the profits, they planned to install running water in one of Ometepe’s communities.

Esterberg traveled with ex-pat water engineer Scott Renfro to San Pedro, a community easily identified as having the worst health on Ometepe. Not only did this little community not have running water and look to the lake to drink from, but they had to haul the water in buckets up a high hill to get it home. Once home, they’d store the bucket where it sat until it needed to be refilled.

Installing running water in San Pedro would be no easy feat. It would take a considerable amount of manpower to carry the piping and all the cement up the steep elevation where they planned to build small dams. If the community committed to building the water system, though, BOSIA would pay the $10,000 price tag.

At that, the community talked for about two hours, weighing the pros and cons.

“You’re not talking about a bunch of relaxed people with extra time on their hands to work on some project,” Esterberg explained.

“But they finally said, ‘For our children, we better do it.’”

One by one, San Pedro started Ometepe on a course to better health. The community was in the middle of constructing the water system when the community next door asked if they could be next, and so on, until all of Ometepe had running water.

“It wasn’t even that Bainbridge made the money for Ometepe to use,” Esterberg said. “It was coming from the coffee they had produced themselves.”

Two-way relationship

Since BOSIA’s earliest beginnings, the people of Ometepe have given back in their own way. This year celebrates 25 years that Ometepinos have welcomed Bainbridge students into their homes to further cultivate the sister island friendship.

“It is a dream come true, that’s what it is,” Esterberg said.

“Because the very way we wanted it, from its most humble beginnings, to grow, it has grown like that. It has grown relationship by relationship, connection by connection.”

Almost 30 years after that first flight to Nicaragua, a group of Bainbridge High School students wait to deboard at the Managua international airport. This time, there are no soldiers surrounding the plane on the tarmac and there is no stop in El Salvador

There is, though, a group of equally anxious Nicaraguan families waiting on Ometepe to meet their North American “daughter” or “brother” that will live in their home for the next two weeks as part of the annual BOSIA student delegation.