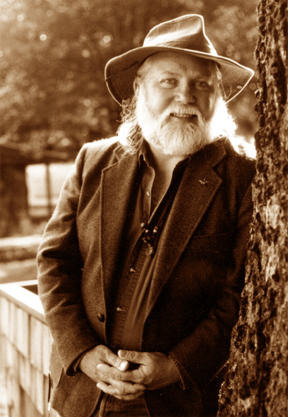

Invertebrate scholar and inveterate teacher Robert Michael Pyle curls his hand into a claw.

“It’s this,” he says, wiggling his digits, “and this,” tapping his forehead, “our opposable thumb and the size of our cranium that makes us the only species capable of lethal alterations of our environment.”

Fortunately for humanity, the naturalist has devoted his dextrous paws and capacious mind to a distinctly different outcome – revitalizing our connection with the world he calls the “more than human.”

That connection is becoming dangerously obscured, says Pyle, by a lack of interaction with the natural world – a theme he explores Friday in his lecture for the Bainbridge Island Land Trust, “Homeland Security.”

The land we call home – it’s a concept that Pyle, author of 15 books and hundreds of essays on natural history, hopes to rescue for the cause of local conservation. At the same time, he says, we must sound the alarm about a political climate that is driving both our neighbor species and our civil liberties to extinction.

“What’s lacking is the recognition that we humans are animals, part of the ecosystem,” Pyle said. “We haven’t come to terms with the limits of our own growth.”

Those limits are ignored by the escalating demands of a burgeoning world population – an unsustainable and ultimately lethal spiral, Pyle says.

“It’s a maladaptive behavior,” he said. “The only way I can explain it is that it is productive of the maximum profit for the minimum number of people over the shortest period of time.”

While the conquest of nature by the powerful is an age-old story – “the image of people in harmony with the environment is pretty romanticized,” he says – it has in modern times found sanction in the dualism of Western religions.

“It’s a form of epistemology, a way of understanding the world,” Pyle said. “It’s the view that people and nature are somehow separate.”

If there were ever a foe of dualism, it’s Pyle, who has straddled the lines between natural and human communities, between science and literature, since his undergrad days at the University of Washington.

“If you think that was OK in 1965 – well, it wasn’t,” he said. “Fortunately, I had teachers who helped me find my way.”

“His way” has been an alchemical union of rigorous fact and riotous feeling – what he calls “walking the high ridge,” a phrase he discovered in the writings of fellow lepidopterist and writer Vladimir Nabokov: “Does there not exist a high ridge where the mountainside of ‘scientific’ knowledge joins the opposite slope of ‘artistic’ imagination?”

“Nabakov gave me the term, but I’ve been doing that all my life,” Pyle said. “Writing with both intellect and emotion, but not letting one obscure the other. It’s been my profession and hobby to reconcile the two.

“I like that. I like being able to be a whole person.”

It’s a passion evident in Pyle’s latest publication, “Butterflies of Cascadia,” which pairs exhaustive desciption of species with the anecdotes of years spent chasing skippers and swallowtails with his two longtime field companions – his wife Thea, a botanist and silkscreen artist, and a butterfly net named Marcia.

Pyle attributes the success of books like “Snow Falling on Cedars” – whose author, Pyle’s longtime friend David Guterson, will introduce him at Friday’s talk – to a similar bridging, satisfying the human longing for the more-than-human world.

If there is hope for preserving biodiversity, it lies in that life-long hunger, says Pyle – and the consequences of ecological starvation, dire. As he put it in his essay, “The Extinction of Experience”: “What is the extinction of the condor to a child who has never known a wren?”

* * * * *

Natural history writer Robert Michael Pyle speaks on “Homeland Security: Protecting the Planet for Humans and Other Species,” at 7:30 p.m. May 9 at Island Center Hall in a benefit for the Bainbridge Island Land Trust.

Tickets are $25, at Eagle Harbor Books, the Glass Onion, Winslow Drug and the BILT office. Information: 842-1216.