The forgotten project could develop the Winslow ravine.

A controversial project that could turn the Winslow Ravine into a heavily developed commercial center is back before city planners – 19 years after winning council approval.

And like Rip Van Winkle awakening after two decades of slumber, “The Canyon” faces a very different world today than in 1984 – myriad new city requirements that present significant obstacles to the plan.

“If the project is required to meet city ordinances, then it is likely that the project will need to go through major revisions to meet current regulations,” planner Joshua Machen wrote in a report issued Tuesday.

But the question is whether the city can apply present law, or whether it must honor the pre-incorporation, Winslow City Council’s 1984 decision, the question in a lawsuit pending before Kitsap Superior Court Judge Leonard Costello.

The project that the council approved two decades ago when proposed by Ronald Comin included seven commercial buildings – one a restaurant straddling the ravine – on a 6.5-acre parcel that includes the parking lot on the north side of Winslow Way, and extends eastward to Highway 305.

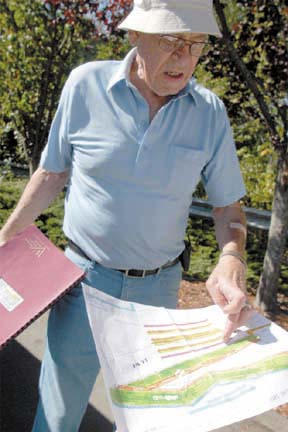

Present owner Larry Stutsman, who acquired the property in 1987, has dusted off those plans and re-submitted them for city approval after his attorney told him that the 1984 go-ahead may still be valid.

“The mayor when I bought the property, Sam Granato, said there was no way the project could be built,” Stutsman said, “and I kept hearing that from the city. All I got was ‘nos,’ so I said the hell with it. But a couple of years ago, my attorney looked at it and said I have a right to pursue it.”

The principal area of conflict is the city’s current requirements for buffer zones – 50 feet back from the highway right-of-way on the east side, and 65 feet from the ravine on the west side, margins that severely restrict the buildable area of the long, narrow parcel.

“That takes 90 percent of my property,” Stutsman said. “They’ve buffered the whole damn thing, and now I can’t use it.”

Far from observing buffers, the old plan put five buildings right on the eastern edge of the ravine; one on the west side, close to Winslow Way; and a 7,700-square-foot restaurant on a bridge suspended directly over the stream.

Project revival

When the Winslow Council approved the project in 1984, it entered into a “concomitant agreement” with Comin setting out the terms under which the project could go ahead, then passed an ordinance endorsing the agreement.

When Stutsman tried to revive the project last year, the planning department told him that regardless of the terms of the agreement, the project would still have to meet current regulations. The required setbacks from both the ravine and the highway dramatically compress the buildable area.

At that point, Stutsman, through attorney Dennis Reynolds, filed suit in Kitsap County Superior Court, asserting that the agreement was a “covenant running with the land,” a right attaching to the property itself, and endured essentially forever.

The city disagreed. It argued that the two-decade interval amounted to a legal “abandonment” of whatever rights the owner might have had.

It also questioned whether the 1984 council could bargain away future councils’ ability to change land-use laws, and said new ordinances made the 1984 agreement “impossible” and therefore invalid.

Last month, Judge Costello denied Stutsman’s request for a favorable ruling as a matter of law, saying he wasn’t convinced the city would reject the plan in its entirety.

So Stutsman resubmitted the 1984 plan unchanged to await the city’s formal response, a process that began with Machen’s memo.

“We don’t know what other alternatives there might be, because we haven’t gone through the process of finding out,” said attorney Dawn Findley, who is representing the city in the case.

In an interview, Machen said that at least partial approval might be possible, although a number of variances would be necessary.

“It could be done,” he said. “It would be kind of neat looking, and might be made environmentally acceptable, but not under current regulations.”

Stutsman indicated that he has re-submitted the 1984 plan consistent with the argument that the old agreement is still valid, but is not, in fact, married to the details of that design.

“We’d just like to use our property,” he said. “I might not want the restaurant, and there are other parts of it we might not want either.

“I’m willing to sit down and talk to the city about it, but so far, they won’t talk to me.”

The matter is scheduled to go to trial in December, but Findley said that might be continued if Stutsman and the city are still going through the process of trying to shape a project that might gain approval.

“It would be more fruitful at this point to determine what might really be available rather than going to trial,” she said.

Ravine review

The Canyon project was born in an aura of both mystery and controversy in 1984.

Proponent Ron Comin was a young man, with no previous track record of island development, when he filed an application for a seven-building development in and around the Winslow ravine.

“It felt like whistling in the wind,” recalls Alice Tawresey, then mayor of Winslow. “The economy was bad, it was going to be very expensive to build, and we felt like it wasn’t going to happen. It seemed like kind of a fantastical scheme, and everybody recognized it as such.”

The plan received a mixed reception from the responsible agencies in what was then the city of Winslow. The planning agency approved, but hearing examiner Walt Woodward recommended against the project, arguing that the ravine needed special environmental protection.

In a move that sparked considerable protest from environmental advocates, the council unanimously rejected Woodward’s recommendation, and voted in favor.

“We all knew (Comin) didn’t have any financing, so there way no way he could make it go,” said Merrill Robison, a member of the Winslow City Council at the time. “How much that was in people’s minds, I couldn’t say.”

Tawresey said the council was feeling some pressure “to make downtown a viable place without doing damage to the environment,” and said she saw council approval as only a tentative first step towards actual construction.

“There were environmental laws in place that would have protected the steep slopes and the streams,” she said. “(Comin) would have had to prove that there would have been no damage.”

The city also would have received a benefit from the project. At the time, much of the property was being used as an auto wrecking yard, and the approval required Comin to clean up the property.

When Stutsman and his wife Von bought the land in 1987 – from a bank, after Comin encountered financial difficulties – they did do the required cleanup, and installed a commercial parking lot. According to Von Stutsman, they offered to donate the ravine itself to the city.

“I went over there to talk to them, thinking it would make a nice park, but they told me they couldn’t take care of the property they had,” she said, adding that she could not recall who she talked to.

Comin left the island, and neither Stutsman nor Tawresey has heard from him since.

Stutsman recognized that the city’s stream-protection ordinances proposed in 1990 would limit his development opportunities, and asked the city to buy the three-acre ravine parcel for $108,000. But then-Mayor Sam Granato argued against the purchase, saying state laws would prohibit any development.

That response angered Stutsman at the time, and still does.

“They won’t buy the land,” he said, “but they want to make it worthless through regulation.”