After he’s ordained, just call him ‘Father Tim’ – it’s much easier.

At one point in his Christian journey, Tim Istowanohpataakiiwa was asked to leave a church because the minister viewed his Native American practices as sinful.

But he did not give up on Christianity, nor did he leave his native traditions behind. He continued searching for a place that would welcome and nourish both, and found “true acceptance†in the Episcopal Church.

On May 7, Istowanohpataakiiwa will be ordained as a priest, one of only three Native Americans ordained in the Episcopal faith in the region. His ordination will be under the auspices of the Episcopal Diocese of Northern California, where he began the process.

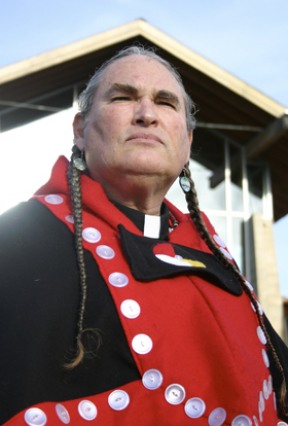

“It has been a long journey,†said Istowanohpataakiiwa, 58, a member of the Siksika and Peigan tribes, who is striking in his long braids, prayer bead necklaces, and shell earrings.

“While I will be ordained for all people, my expertise and heart-love is with my people, and that is where my strength is.â€

The ordination will take place at Grace Episcopal Church on Bainbridge Island, where Istowanohpataakiiwa – whose name means “captures the long knife,†from a tribal battle story he sees as a tale of justice – serves as a deacon. Last week, the church voted to make him “Missioner for Native Ministry,†supporting his outreach to tribal communities throughout Kitsap County.

“He has this gift of reaching out to people that the church has traditionally ignored,†said Bill Harper, the vicar at Grace church. “We want to send him out to do pastoral work, knowing that he has a community of people behind him, supporting him.â€

Istowanohpataakiiwa is seen as bridging two cultures that often have little interaction between one another. Since he started attending Grace church as a seminary student two and a half years ago, his Native American songs, drumming and storytelling have become occasional features of worship.

When the congregation celebrated the construction of its church on Day Road two years ago, Harper asked Istowanohpataakiiwa to open the ceremony with drumming and songs to the eagles on the property, which seem to circle overhead whenever the Suquamish resident gives a sermon.

“He comes from an oral tradition and he is a storyteller,†Harper said. “His stories open us up to the natural world, reminding us of the sacred nature of creation.â€

Istowanohpataakiiwa recently told the congregation the Adam and Eve story, with a Native American interpretation: The Creator scooped mud from the Earth and made a man, strong and tall, and a woman, curvy and soft. But they just stood there, inanimate. So Creator blew on the back of their heads, and they came to life — which also explains why people have cowlicks, Istowanohpataakiiwa said, drawing laughter from the congregation.

“In a way, he is the missionary to us,†said Grace church parishioner Kathie McCarthy. “Tim is the missionary of Native spirituality to our community and I’m grateful for that.â€

While officiating in church services, he wears a bright red and black “button blanket†made by native elders in British Columbia.

The cloak bears Native American symbols depicting himself with a beaver and a medicine stick, which tells the story of his clan, and an eagle, with whom he shares a special relationship.

“The eagle represents power and prayers,†Istowanohpataakiiwa said.

Reaching out

He has already begun ministering to Native families in the region, and eight Native people are waiting to be baptized by him. When the weather warms in June or July, they will be brought into the faith in the waters off Old Man House Park, the mother village of the Suquamish tribe, and home to Chief Sealth.

“The Native people have to understand they can be fully Native and fully Christian, without giving up who they are,†said Istowanohpataakiiwa, a 2002 graduate of the Native Ministry Program at Vancouver School of Theology.

“There is a great need for healing among our people, for all the anger and hurt and trauma we have experienced over the years.â€

Among those hurts: the way Native Americans have been forced to deny their heritage in some churches, such as the evangelical denomination in California in which Istowanohpataakiiwa grew up.

“We were the only brown ones,†he said of the congregation he attended with his grandmother. Later in life, when he tried within that church to integrate his Native and Christian sides, he was shunned and asked to leave.

“They tried to put a square peg in a round hole, which makes you less than you are,†Istowanohpataakiiwa said. “You should not have to cut off part of who you are in order to fit.â€

He was well into adulthood and had a long career in law enforcement when he found “real acceptance†for his Native side in the Episcopal church of a friend.

This led to a call to ministry. During his theology training, he worked for a time as a chaplain in jails. After a 30-year career that included sheriff’s patrol work and crime scene investigations, he said, “I am not that easy to con.â€

In his preparation for ministry, Istowanohpataakiiwa has counseled those with drug and alcohol addictions and he has worked in jails, where many people with substance abuse issues end up.

In the early 1990s in Roseville, Calif., Bishop Jerry Lamb asked Istowanohpataakiiwa’s help in creating Episcopalian services that “spoke†to the Native Americans living in that region.

“It took be two to three seconds to say yes,†he said. “We wrote our own liturgy, our own songs, our own Eucharistic prayers, making them all very native-friendly,†he said. “We started our own church.â€

He would like to do the same in Kitsap County, translating prayers into the Salish language of this region’s native ancestors.

“We will build the people first, and do the healing, and a church will follow,†although this could take years, he said.

In the meantime, Istowanohpataakiiwa hopes to become the bridge between the islanders at Grace Church who have provided the seed money for his ministry, and the native people his ministry will serve.

He sees the two sides of himself – Episcopal priest and Native American sundancer – coming together to serve others in a unique way.

“The whole center of my ministry is focused on healing,†he said, “healing of both peoples to live in harmony with one another.â€