The first lawsuit has been filed against the city of Bainbridge Island for its update of city regulations that cover development of properties that contain “critical areas,” environmentally sensitive features such as wetlands and steep slopes.

Bainbridge adopted its new critical areas ordinance on a split 4-3 vote in late February, but the regulations have been criticized by residents, homebuilders and others as an “lopsided, unjustified land grab.” Those complaints center on new regulations that include greater restrictions on land that’s considered “critical aquifer recharge areas.” All of Bainbridge Island — except for shoreline areas and the island’s designated places for more dense development (downtown/Winslow Center, business/industrial areas, Rolling Bay Center, Island Center and Lynnwood Center) — falls within the critical aquifer recharge area.

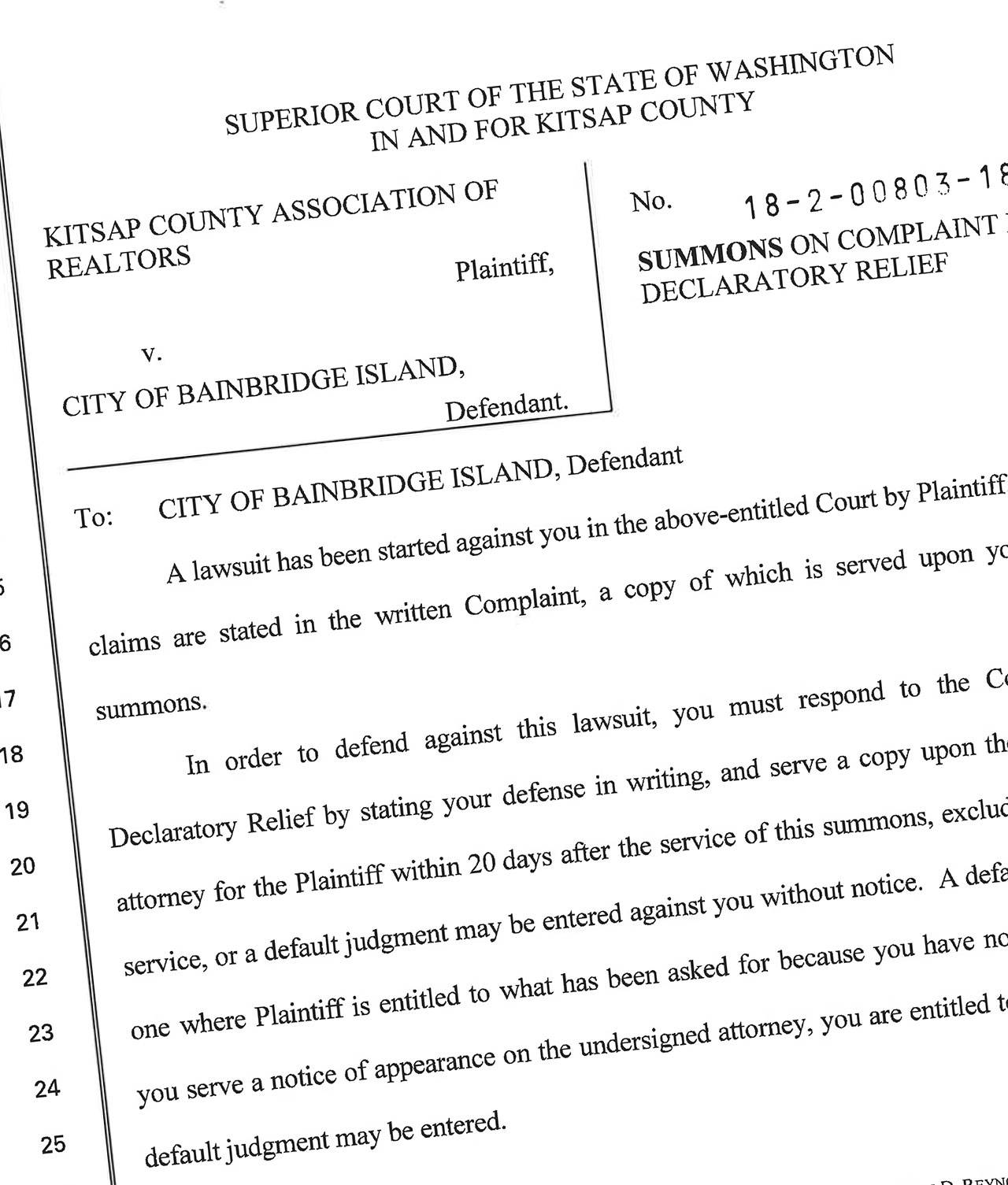

Last week, the Kitsap County Association of Realtors filed a lawsuit against the city in Kitsap County Superior Court.

Dennis Reynolds, a Bainbridge attorney who is representing the association, said in court documents that the new regulations are unconstitutional in multiple ways and the city’s adoption of the rules is “unduly oppressive, arbitrary and unreasonable.”

Reynolds also said the new rules conflict with the state’s Growth Management Act, the expansive law that regulates urban development and protects farm and forest lands.

Reynolds claimed the new regulations are an attempt by the city council to halt new development on Bainbridge.

“The facts will show that the onerous requirements of the [critical areas ordinance] are imposed to restrict if not outright prohibit new growth on the island, as passed by a new city council elected on a ‘save the trees’ platform,” Reynolds said in the lawsuit.

The Kitsap County Association of Realtors represents roughly 650 Realtors and 40 affiliate companies. In the lawsuit, filed March 20, Reynolds repeated many of the concerns he presented to the council when a draft version of the new rules was made public last fall.

Reynolds said the new rules constitute a “taking” of private property for a public use without just compensation, because the regulations require landowners to leave at least 65 percent of their property undeveloped as an “aquifer recharge protection area.” He said the entire island had been designated as a “critical aquifer recharge area” under the new rules, which would require a permit for any work done on land zoned for residential uses.

Reynolds also noted the city could have adopted “less onerous methods” to protect the island’s aquifers, such as infiltrating treated water from its wastewater sewage treatment plant. The city’s adoption of the rules also violated requirements for due process and public participation, he added.

In the lawsuit, he asked the court to declare illegal the city ordinance that established the new rules, and to grant a preliminary injunction against the enforcement of the rules while the lawsuit was still in court.

City Attorney Joe Levan did not immediately respond to a request for comment this week from the Review; city officials have 20 days to respond to the lawsuit. Reynolds noted in court documents that the lawsuit won’t be the final legal challenge to the new regulations. He said the new rules would also be contested via the Growth Management Hearings Board, a group that resolves land-use disputes arising from the Growth Management Act.