PORT ORCHARD — It’s a common refrain after news breaks about another celebrity suicide: “How could this person, with so much to live for, have nothing to live for?

That’s the mystifying question puzzling so many when, in about a week’s time, two globally known, strong-willed and well-liked individuals — chef and television storyteller/traveling raconteur Anthony Bourdain and women’s handbag maven and businesswoman Kate Spade — were found dead, their lives cut short by their own doing.

The list of celebrities who committed suicide in recent years is certainly noteworthy: comedian/actor Robin Williams, Chester Bennington of the band Linkin Park, “Top Gun” film director Tony Scott, NFL linebacker Junior Seau, Seattle-born Soundgarden singer Chris Cornell, DJ master Avicii and country artist Mindy McCready, to name just a few.

Their shocking suicides might seem to signal a disturbing new pattern among high-profile trendsetters. But the reality is that the specter of suicide is touching countless troubled lives in every-town America — and growing at an alarming rate.

If you’re a celebrity or a seemingly average Kitsap community member, suicide doesn’t discriminate as a mental health disorder. In fact, it’s the leading cause of death in the U.S. Statistics indicate that more die from suicide than those killed in auto accidents. And it’s a final outcome that inflicts heavy collateral damage among grieving family members and friends who are left behind.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that nearly 45,000 lives were lost to suicide in 2016, a significant increase after decades in which statistics were stable at 32,000 deaths yearly. Most recently, suicide rates rose by more than 30 percent in half of the states in America. Kitsap County mirrors the statistics in Washington state; 16 deaths per 100,000 residents were attributed to suicide. In this county, that number is 20 per 100,000, an increase from 13 in 2000.

Statistics also report that suicide claims men as its victim twice as often as with women. As a subset, the group with the highest suicide rate includes middle-aged white males. But suicide deaths by women have increased in recent years from a more predictable time when men died at a rate three to four times that of women. Now, men are victims twice as often.

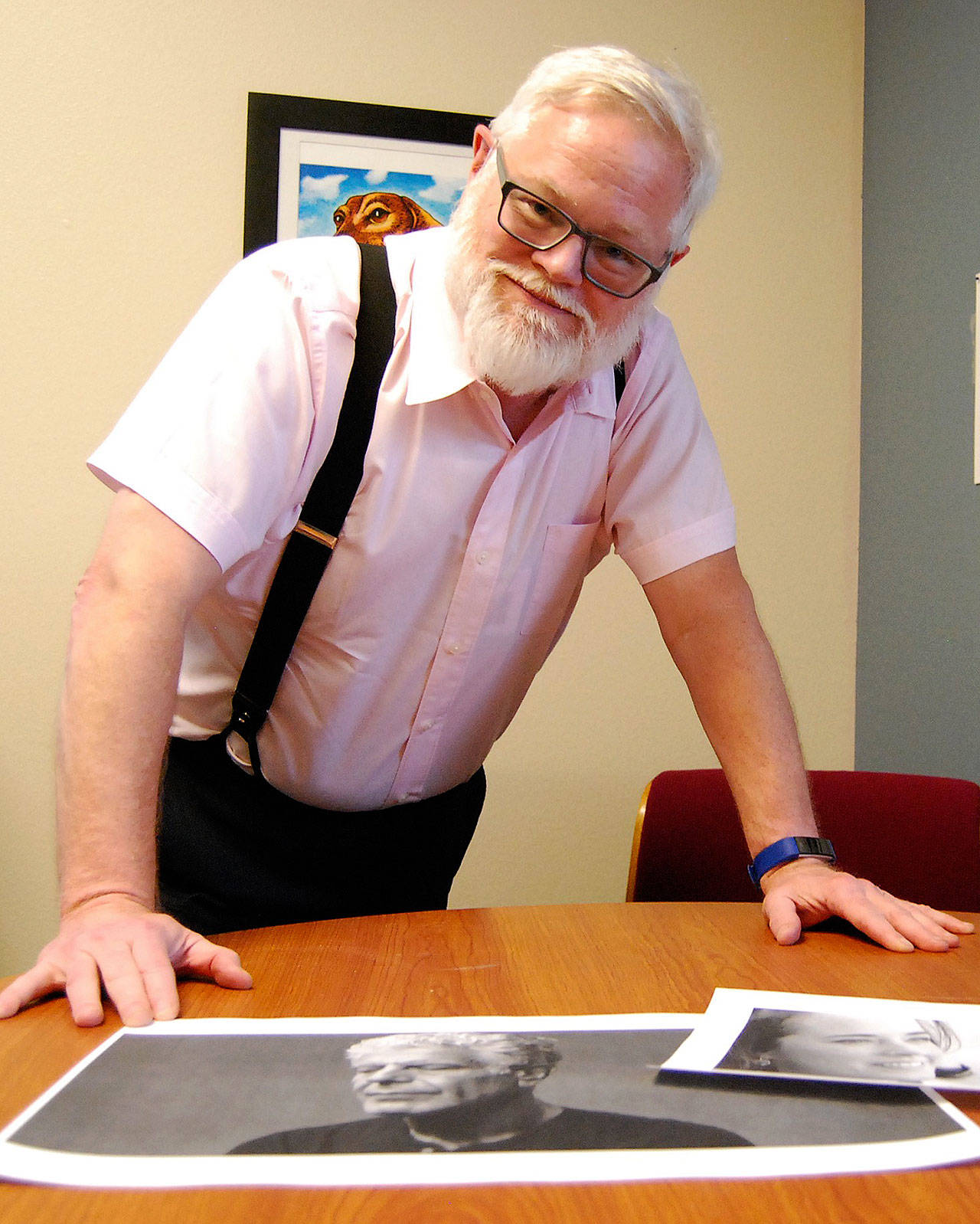

Kelly Schwab, program manager of the Crisis Clinic of the Peninsulas in Bremerton — associated with Kitsap Mental Health — supervises a team of 26 volunteers who answer calls from people dealing with a mental health crisis.

Schwab is familiar with those statistics. He estimates the crisis clinic responded to a little more than 10,000 calls from a three-county region: Kitsap, Jefferson and Clallam. While a minority of the calls — he said about 2,000 last year — were suicide-related, all the phone-based interventions involved mental health crises.

“We have seen a slight uptick in calls about suicide over the last few years,” Schwab said. “Nationwide, there has been a 28-percent increase in [crisis] calls. All of our calls are going up.”

Statistics don’t lie.

“You can just see the [statistical] line moving straight up. There are a lot of reasons behind that, which have to do with societal changes.”

Collecting and calculating statistics on suicide rates is the easy part. More difficult is finding conclusive reasons from among ambiguous data as to why the rates are rising.

“No matter how successful a person is, they can get cancer, they can get sick,” Schwab said while outlining a diagnostic profile of a person who might be considering suicide. “It’s a mental health issue, and mental health is a sickness, just like any other illness. It doesn’t matter how rich you are, you still can be in pain.”

Dr. Jeffrey Lieberman, chair of the Psychiatry Department of Columbia University and New York Presbyterian Hospital, told “CBS Sunday Morning” he believes the spike in suicide deaths is partly attributable to the nation’s healthcare system.

“It’s because our country has a dysfunctional and inadequate health policy, particularly when it comes to mental health care,” he said. “Death should not be an outcome of mental illness. We’re better today than at any time in human history in predicting and preventing suicide.”

People in crisis who need evaluation and follow-up care often are reluctant to get it for reasons beyond denying or minimalizing their personal crisis — healthcare services are expensive, even for those who have a modicum of insurance.

Preventing suicide heavily relies on an afflicted person receiving prompt medical treatment from observant healthcare professionals. But before being treated, that individual must be identified as needing treatment. And that’s the tricky part. Liberman and Schwab both agree that a person with depressive symptoms often works hard to disguise them.

“Suicide doesn’t happen spontaneously, out of the blue. Ninety percent of people who commit suicide have a pre-existing mental disorder, whether it’s diagnosed and treated or not,” Liberman said.

According to the CDC, 54 percent who died by suicide were undiagnosed with a mental health condition, most often depression. For Bourdain, his demon was a history of depression for which he self-medicated by using drugs, most notably heroin and cocaine. And Spade, the epitome of sunny optimism, was known to have struggled with bipolar disorder.

“We’ve found that people are becoming more lonely,” Schwab said. “Connections to people is the biggest buffer to suicide.”

Even then, that connection some have may just be a facade; the cloak of depression often is invisible to almost everyone near and dear someone who is chatty and amiable in public, but suffering mental anguish in silence.

“Even though a person may seem to be surrounded by friends — and these two [celebrities] had all kinds of people in their lives — their depression started to make them feel isolated and unable to express emotions,” Schwab said.

While most who contemplate suicide wear a mask of normalcy on the outside, there are warning signs — some subtle, others more evident —that they exhibit during their daily lives. For friends and family of a loved one in crisis, Schwab said it’s critical that they help now, not after it’s too late.