His portfolio of editorial cartoons in hand, Burris Jenkins Jr. arrived for a job interview at The New York American one day in 1931 and mistakenly got off the elevator at the wrong floor. He found himself in the sports department of the rival Evening Journal, where he was hired on the spot as a sports cartoonist.

Four of Mr. Jenkins’ magnificently detailed drawings, completed on deadline in the 1930s, hang in my den — reminders of one of the great sports cartoonists of all time and also that, for this unique style of journalism, time is practically up.

With newspapers fading away, leaving some communities with little or no local coverage — such as next month’s announced closure of the Youngstown Vindicator in Ohio, where a newsroom staff of 44 will be out of work — maybe the passing of a journalistic subcategory like sports cartooning is, sadly, beside the point. That’s too bad, because the artists who attended games and often completed their drawings right in the press box worked magic in fans’ minds far more effectively than today’s daily deluge of Web Gem videos.

Four other originals on my wall are by Willard Mullin, widely considered to have been the dean of sports cartoonists during the craft’s heyday from the 1930s through the ’60s. It was Mr. Mullin who, in 1937, invented the unshaven Brooklyn Bum character which stuck as the unofficial mascot of the Dodgers until the team moved to Los Angeles for the 1958 season.

Mullin drawings are notable for the care with which the artist captured athletes’ physiques. The images he conjured were not funny so much as fascinating. One of my favorites depicts players from the Yankees, White Sox and Orioles chasing each other in a tight circle as just two games separated the three teams battling for the 1964 American League pennant.

Mr. Mullin’s distinctive signature consisted entirely of vertical lines, like blades of outfield grass. Each drawing has a note in the lower corner — unseen by readers — underscoring the tight deadline: “5 a.m. Sports,” meaning a messenger had to get the artwork to the offices of the New York World-Telegram in time for the paper’s first edition.

What little remains of this dying art is practiced by only four newspaper sports cartoonists whom I know of. Drew Litton in Denver used to draw for the Rocky Mountain News and has been syndicated since the paper’s death in 2009. Jim Thompson at the Los Angeles Times, Mike Ricigliano of the Baltimore Sun and Rob Tornoe with the Philadelphia Inquirer round out what’s left of the roster.

But none of today’s sports cartoonists does daily game drawings as Mr. Mullin and Mr. Jenkins did, or like the late Bill Gallo of the New York Daily News, a 50-year legend and inventor of the Mets’ washerwoman fan, Basement Bertha. That sort of deadline drawing was depicted in the 1984 film “The Natural,” in which Robert Duvall’s character, Max Mercy, creates press box art with sly captions such as “Is (Roy) Hobbs going from leader to goat?”

Most newspapers have chopped away at the space given to sports coverage, leaving little room for cartoons. Moreover, with reporting staffs being slashed, it is unthinkable to pay a full-time salary to an artist whose entire daily output is a single drawing. And with 24/7 game coverage on cable and the internet, sports cartoons seem as old fashioned as courtroom art became the moment TV cameras were allowed at trials.

For me, sports is as much an emotional experience as a physical event. That’s where the great cartoonists entered the game, capturing on the printed page what so many diehards were feeling.

Fans will continue to wonder if anyone will ever hit as many homers or sink as many baskets, but it’s no use debating whether anyone will ever draw as well as Jenkins and Mullin, because that game is over.

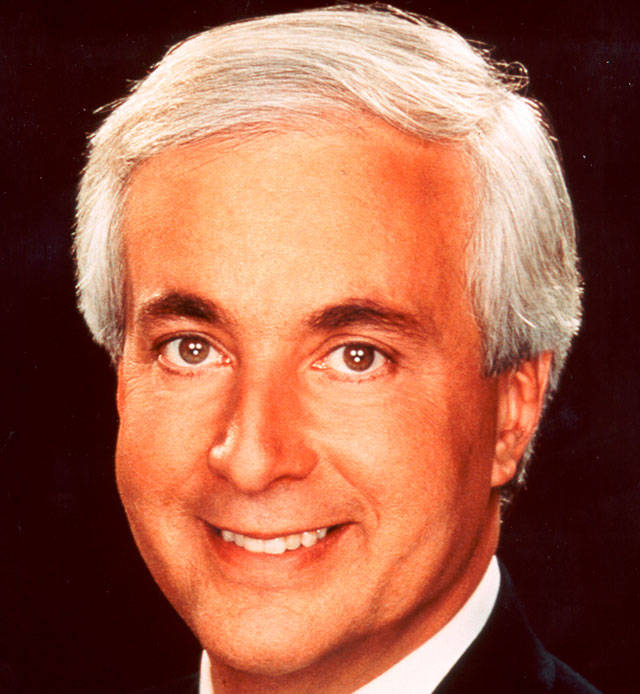

Peter Funt is a writer and speaker. His book, “Cautiously Optimistic,” is available at Amazon.com and CandidCamera.com.