Is it art?

That’s the question that has dogged photography since the earliest days of the medium. There was some perhaps understandable pushback from painters and illustrators of old to the young upstart discipline’s claims to art, but one man, at least, knew better.

Alfred Stieglitz was an American photographer and instrumental art promoter who was arguably the main driving force in making photography an accepted “serious” art form, most especially through his founding of the “Photo-Secession” movement in 1902.

The so-called Secessionists (including the famed Edward Steichen) promoted photography as true fine art, the practice of pictorialism (basically any style in which the photographer has somehow manipulated what would otherwise be a straightforward photograph as a means of “creating” an image rather than simply recording it) especially.

According to “Impressionist Camera: Pictorial Photography in Europe, 1888–1918,” by Patrick Daum, a pictorial photograph typically appears to lack a sharp focus (some more so than others), is printed in one or more colors other than black-and-white (ranging from warm brown to deep blue) and may have visible brush strokes or other manipulation of the surface.

“For the pictorialist, a photograph, like a painting, drawing or engraving, was a way of projecting an emotional intent into the viewer’s realm of imagination.”

The Bainbridge Island Photo Club will be cranking up their collective imaginations this month with a special abstract photography appreciation event, “Once In A While Give Photorealism A Rest,” at 7 p.m. Wednesday, April 11 at the Waterfront Park Community Center (in Huney Hall, 370 Brien Ave. SE).

Admission is free and open too all.

The evening’s two-part program includes a discussion and the sharing of images by David Warren and Rob Wagoner, BI Photo Club educational chairman.

In Part I, Warren will share a short history of Impressionism and Abstract Expressionism, with corresponding examples and his own related images, in an examination of camera uses alternative to straight documentation.

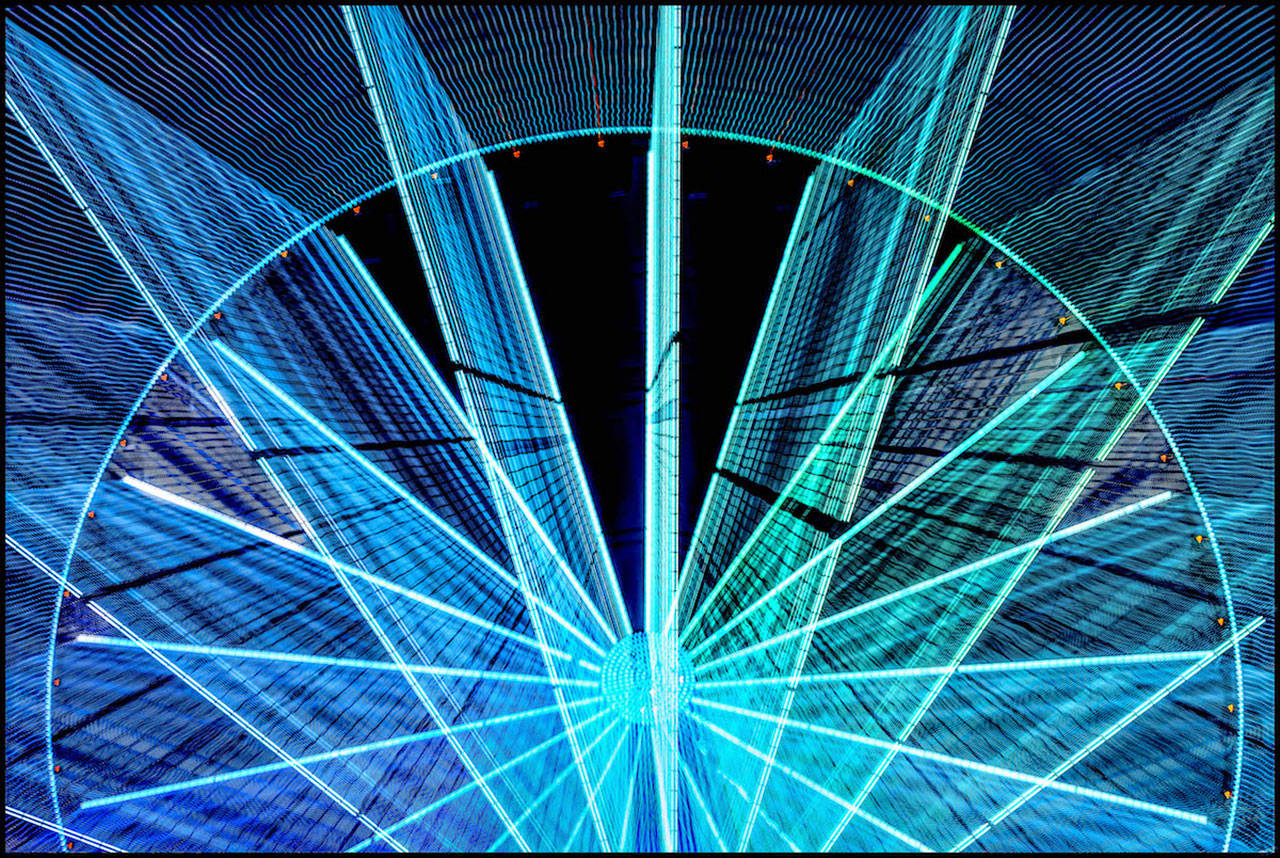

In Part II, Wagoner will display a series of his own images of the Seattle Ferris Wheel in an exhibition he calls “A Space Odyssey.”

The pictures were made over the course of three nights using various lenses and some very long exposure times.

In a world where we’re obsessively documenting everything all the time, Wagoner said, it can be fun and refreshing to take a step away from the real world and remember photography’s more abstract capabilities.

“Most of the people in the photo club are sort of realists in what they shoot,” he said. “The camera’s really a way of documenting history.

“It’s a different perspective, a different point of view,” Wagoner explained. “I’m going to try and see if I can get people to loosen up a little bit.”

Also in April, the photo club will be hosting a double-feature movie night, screening two documentaries about famous image makers: “The Spectre of Hope,” about fine art/documentary photographer Sebastião Salgado, and a second film about David Hockney, an important contributor to the pop art movement of the 1960s, and his iconic “joiner” collages.

Salgado is renowned for his work’s blending of fine art and documentary styles, typically in very high contrast black and white. He has traveled in over 120 countries for his photographic projects, most of which have appeared in numerous press publications and books. Touring exhibitions of this work have been presented throughout the world.

Many of his most famous pictures are of a gold mine in Brazil called Serra Pelada.

“The Spectre of Hope” recounts the six years he spent traveling to about 40 countries, taking pictures of globalization and its consequences — most notably, the mass migrations of populations around the world.

In the film, Salgado presents his remarkable photographs in conversation with John Berger, famous English art critic, novelist, painter and poet.

“Sebastian Salgado is one of my favorite photographers,” Wagoner said. “It’s kind of a gut-wrenching film. He’s a really great human being in terms of trying to help the plight of poor people in the world.”

Hockney is an English painter, draughtsman, printmaker, stage designer and photographer. In the ’80s he began arranging photo collages, which he called “joiners,” using Polaroid and 35mm pictures. The end result is an image emerging from what appears to be a randomly scattered pile of pictures — though is actually a careful arrangement. Many of the finished products include photographs taken at different places and at different times, ultimately combined to form a single collective image.

Admission to the double screening is free and open to the public. Popcorn and drinks will be available, with the entire program set to run about 100 minutes.

Visit www.biphotoclub.org to learn more.