“I’m sorry for your loss” works with inanimate objects, the kind of loss you can be vague about, like a purse or half a pair of socks or electrical power.

In the presence of real grievers, though, in the face of death and finality, the forever deprivation of uniquely beloved people, Hallmark words, in their uniformity and distance, are so hollow. What can we possibly say to take away the pain?

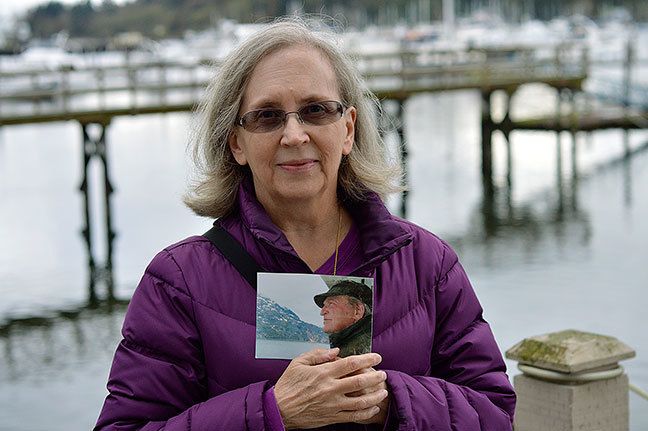

Matthew Gaphni

“Our society doesn’t do grief well,” Robin Gaphni says on a Friday, six days after the sixth anniversary of her son Matthew’s death. “We kind of push it down. We feel like, ‘Just get through this. You have your three-day bereavement leave and then carry on.’”

But Gaphni knows firsthand: grief doesn’t have a timeline.

Her son, the hiker, the fossil collector, downhill skier, was an accounting major, a senior at Western Washington University, when he contracted strep six years ago. By the time his doctors figured out what was making him sick, the infection had attacked his heart valve.

“It’s the worst thing you can imagine,” Gaphni said, recalling her son’s death.

That first year was a fog, as Gaphni recovered from the shock, but she pushed herself to keep exercising and working. Her then-employer was very supportive, she said, and allowed her to work on her own terms. Her friends, too, didn’t try to put expectations on her mourning. They just listened.

It was a tough winter after Matthew died; ashen skies and bitter temperatures that seemed to match Gaphni’s sorrow. She remembers how a friend called her and insisted they walk around Battle Point Park with headlamps in the dark. “We couldn’t look at each other because we’d blind each other. And she just started asking questions about Matthew,” Gaphni said. Her presence, her lack of judgment, her willingness to listen and not try to fix anything was therapeutic.

Gaphni didn’t heal on a Tuesday, after 22 long cries or in any neat timeline, but after 18 months, she felt like something had changed. Gratitude was bubbling under the surface of her pain, and she wanted to share it. She began blogging about her transformation and the power of grief at www.griefgrati tude.com.

The other shift that happened was in Gaphni’s professional life.

Island Volunteer Caregivers, the nonprofit that zips people around to doctor’s appointments and Safeway and knitting circles and movies, had an opening. Their grief support group, which has existed for over a decade, needed a second facilitator.

Gaphni, with an arsenal of tenderness, stepped in.

Jack Root

Before he retired, Teresa Root’s husband Jack was an aerospace engineer. He also was a talented woodworker and all-around problem solver, his handiwork enshrined in the couple’s home, furniture and a 40-foot diesel cruiser, which came to life in their backyard over seven years.

“Jack loved to be on the water,” his widow said. “I think that’s where he was happiest. He motored all around Puget Sound in [that diesel cruiser], and he loved to fish, especially for salmon.”

Root joined the grief support group for a year after Jack died, in 2014, finding, surprisingly, that the company of strangers was the most comforting place to be.

“The thing about people who love you but have never been through grief, they have the best intentions but they don’t really understand it,” Root explained.

“They want you to be happy and they want that so badly that sometimes you have to pretend you’re happier than you are.”

At the start of each session, Gaphni would present a dish filled with sand and ask each person to light a candle.

“This is for Jack, my husband,” Root would say, as she swirled the tiny granules of glass and rock around the dish.

She liked the simplicity of the ritual. She also liked the quotes Gaphni would clip for her each week. One evening, it’d be a Pueblo blessing urging Root gently forward. Another week, a simple poem might be her fresh air. She let the words hold her, long after each group was over, after she had talked about Jack and how death was hard and so many ripe and overwhelming emotions.

“There is no path so dark, nor road so steep, nor hill so slippery that other people have not been there before me and survived,” Root might reread. “May my dark times teach me to help the people I love on similar journeys.” (Maggie Bedrosian)

Compassionate Companions

In March, a couple presented Gaphni and the board of IVC with a proposal: John Ruark, a retired psychiatrist, and his wife Terry wanted to bring a companioning program to the island, modeled after a grief support service they had shepherded in San Francisco. Compassionate Companions, as it would be called, would match the bereaved, those experiencing a fresh loss with those farther along in their mourning.

Root was at the top of Gaphni’s list for companion recruits; two years after the death of her husband, she said a good side effect of her loss was that her heart had grown two sizes bigger.

Still, she was intimidated when Gaphni asked her if she might be willing to meet up with another widow.

“I had this fear when they first asked me that I was supposed to be some expert and be really smart about how I talk to these people,” Root said.

Although she received ample training — including two eight-hour sessions with Ruark on attachment theory, the lock-eye bonds we form from infancy — Root discovered that she didn’t need anything but her ears, really.

She was there to sip coffee. She was there to listen.

Aaron Waag

Teri Waag was another support group graduate who Gaphni asked to serve as a companion. She lost her son Aaron six years ago in January.

Aaron, 29, was married to Ashley, who worked in the Town & Country bakery. He loved the outdoors and fishing and taking his newborn baby, Abigail, to Point No Point beach. She was 1-year-old when her daddy fell from a crane and died suddenly.

For a while, Waag was wracked with guilt over the accident.

“We had a tree company, so he worked for us. That part was really hard because we felt like, gosh, ‘If we hadn’t rented the crane that day…,’ those kinds of things.”

But as Waag wrestled with what happened, she started to sense that Aaron was speaking to her, trying to release her from responsibility.

Waag had dedicated a scripture verse to her son when he was born — “They that wait upon the Lord shall renew their strength; they shall mount upon wings like eagles” — and, after the accident, that eagle theme just kept showing up unexpectedly.

First, racing to the hospital: Waag got the call about Aaron falling while she was driving.

“And this eagle just swooped over our windshield and flew up over the Olympics,” Waag said. “I looked at my clock and thought, ‘He’s gone home.’” It was 10:31, she later learned, the very minute her son had left them.

Next, right before the funeral service at the Kiana Lodge, where Aaron and Ashley had also been married, Waag found an eagle feather lying on a doormat. She had never noticed eagles before. She wasn’t even thinking about eagles when she assigned her son that verse. This couldn’t be random, she remembered thinking.

Waag’s trauma counselor, who was part Cherokee, also believed the sightings meant something.

“In my culture, the eagle represents God, and God wants you to know that Aaron is with him,” Waag remembered him saying.

“So we just kind of embraced that,” she said. “I determined at that point, to honor Aaron’s life, I wanted to speak into the lives of other people who are going through such tremendous loss.”

Between shifts at Town & Country, where she works part-time as a checker, Waag is writing a children’s book about grief from the perspective of an eagle, soaring above Abigail, dropping feathers. She wears a bracelet her sister etched with the title, “Angel Feather.”

Like with Root, Waag’s journey also led her to Compassionate Companions. Every week, she sees another grieving mother. Usually, they meet for lunch, but they’ve also walked the Hall’s Hill Labyrinth together.

“I think we’ll maybe be friends for life,” Waag said.

Friends for life, friends in death.

As Rumi said — and Gaphni signs on all her emails — “We’re all just walking each other home.”

Grieve together

If you’ve recently lost a loved one and would like to participate in the Compassionate Companions program, contact Robin Gaphni at robin@ivc.org. She will match you with a companion based on schedule and personality.

A new grief support group will begin in January. Meetings are closed to ensure continuity. Contact Robin for more information.