There’s a scene early in “Breakfast at Sally’s” in which Richard LeMieux and his golf buddies sit in a diner outside Bremerton en route to a tee-off, discussing the increase in the town’s homeless population.

LeMieux, a rich man and a conservative one, wonders aloud why the city doesn’t just chase homeless people over to Seattle to work at McDonald’s.

From the standpoint of memoir, LeMieux’s diner scene is one of classic foreshadowing. In the moment, he didn’t have a clue.

“I didn’t know about homeless people,” LeMieux said. “Most people don’t. They see them sitting on a street corner in Seattle or wandering around.

“And I never dreamed… If people would have said to me that when I was 59, I’d be homeless, I would have laughed. That would never happen to me. I’m either too strong, or too vibrant, or too hardworking – none of that will ever happen to me.”

Not long after that breakfast, LeMieux’s lucrative publishing business went under. He lost everything, by degree, until in the summer of 2002 he found himself living in his van, slipping deeper into a depression that eventually led him to attempt suicide by jumping off the Tacoma Narrows Bridge.

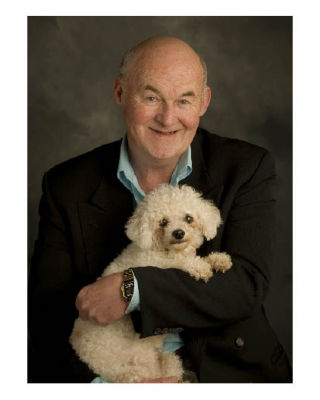

Hearing the voice of Willow, his “Wonder Dog,” brought LeMieux back. As she barked frantically from the van, he swung his leg back over the guardrail, made his way back to her, and continued the resigned process of living day to day.

The more people LeMieux met through the network of church basements, library reading rooms, Salvation Army kitchens and overnight parking lots in Bremerton, the more he began to listen to their stories.

Their tales and banter, along with a desperate wonder about how he himself had fallen so far, led LeMieux to begin jotting down scenes and snippets. He’d later transcribe the notes, adding commentary and personal remembrances to this “basic reporting” using a temperamental typewriter he acquired for free at a local secondhand shop.

What LeMieux learned during his time as a homeless person, and what led to the eventual publication of “Breakfast at Sally’s,” can be illustrated semantically: The people he met were not, as he’d once referred to them, “the homeless.” Instead, they were individuals and families with faces, stories and pasts. None of them wanted to be there, and many of them weren’t quite sure how they got there.

For the first time, LeMieux said, he was really looking at homeless people. And coming to understand that, like him, they’d once had something different.

“And all of a sudden, it’s not there,” he said. “And I see that in their eyes, and their mannerisms. And then slowly but surely they acquiesce to living the best they can.”

LeMieux said the writing at first felt purposeless; at one point, he tossed the typewriter and his first 30 pages into the dumpster at a campground. A campground regular, Michael – one of many characters readers meet in “Sally’s” – retrieved and repaired the typewriter and presented it to LeMieux.

Signs and small acts of kindness like this seemed to occur daily, often at the very moment LeMieux thought he was done for, twining around the relentless vicious cycle of homelessness: With no address, one couldn’t get a bank account or establish credit; with no credit, one couldn’t get a place to live.

These acts, along with Willow’s unflagging companionship and the network of charitable organizations in Kitsap County such as Mental Health Services, the Salvation Army, and Bainbridge Island’s Helpline House, sustained him.

“It’s the day to day, people to people, spreading love and kindness and graciousness to each individual as best as possible,” he said.

After two years of living in his car, LeMieux was given permission to use the scratchy floral sofa in the basement of Bremerton’s First United Methodist Church. The arrangement was intended to be temporary; LeMieux stayed for nine months.

He credits Willow’s charm as his “in” with the congregation, which originally regarded him as “spooky.” Mutual honor, dignity and respect were the qualities that helped him establish a warm relationship with congregation members, one of whom eventually agreed to co-sign a rental agreement on a small apartment, where he still lives.

“The community, the people, one after the other – little miracles have kept me alive to the point where I’m going to wake up tomorrow morning and say ‘Thank God I’m alive,’” he said.

As to “Breakfast at Sally’s” – Sally’s, if it’s not obvious by now, was the regulars’ nickname for the Salvation Army – LeMieux continued plugging away, with encouragement from various camps. The book’s publication has led to an unexpected burst of local and national attention, from a public radio interview this week in Seattle to upcoming appearances in New York, Pittsburgh, and then Columbus, Ohio. There he’ll speak at a regional Salvation Army kick-off event, which he anticipates with self-effacing wonder.

“The only reason I’m getting to go is because Della Reese fell down and broke her foot,” he said.

Back at the diner scene in “Sally’s,” Ted, LeMieux’s more liberal friend, makes a couple of pointed remarks in response to the future author’s McDonald’s comment. First, he says, homeless people need help, and respect, and kindness, because their minds, hearts, spirits and sometimes bodies are broken. And, he adds, it could happen to any of the men sitting at that table.

“I spent most of my life taking care of myself, and thinking of myself, and never really understood some parts of the world,” LeMieux said. “I never had the heart for homeless people. I didn’t know how to help. And I never thought I’d be homeless.”

LeMieux’s hopes for the book are straightforward: that it will help put a face on homelessness, and generate the type of empathy that will actually lead to action. Not necessarily even on a grand scale.

“I don’t know if I have a cause, but people who have picked up the book and read it now do things they didn’t do before, like take toiletries to the Salvation Army. They have a more empathetic feeling, more understanding,” he said.

“If somewhere in the process of all this, if one person gets off the street because of this book, that’s cool. If thousands do, that’s even better. It is a mission, hoping that hope actually turns into something. Because sometimes hope doesn’t.”