Photography is the power to control time.

With just a click of the shutter, you can freeze it, preserve a moment and with one look at the resulting photograph easily recall that second many years later.

It is proof. It is commemoration. It is a souvenir. It is a record. By its very nature though, it is static. We, and the world, change around the photograph. That is what lends each image such power: consistency; a seeming imperviousness to the constant ravage of time.

Nonsense, says Meghann Riepenhoff.

Her best images are never finished.

“Nothing is, and I wanted to speak to that in the work,” said the Bainbridge-based fine art photographer. “Whether we’re looking at ourselves in sort of immediate human-time scale or geologic-time, change is inevitable. I wanted my work to point to that.”

Riepenhoff was among the 173 recipients of a 2018 Guggenheim Fellowship, as recently announced by the board of trustees of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. In particular, she was selected for her image series “Littoral Drift,” a project that is all about change at every step of the creation process — even long after the image is printed and framed.

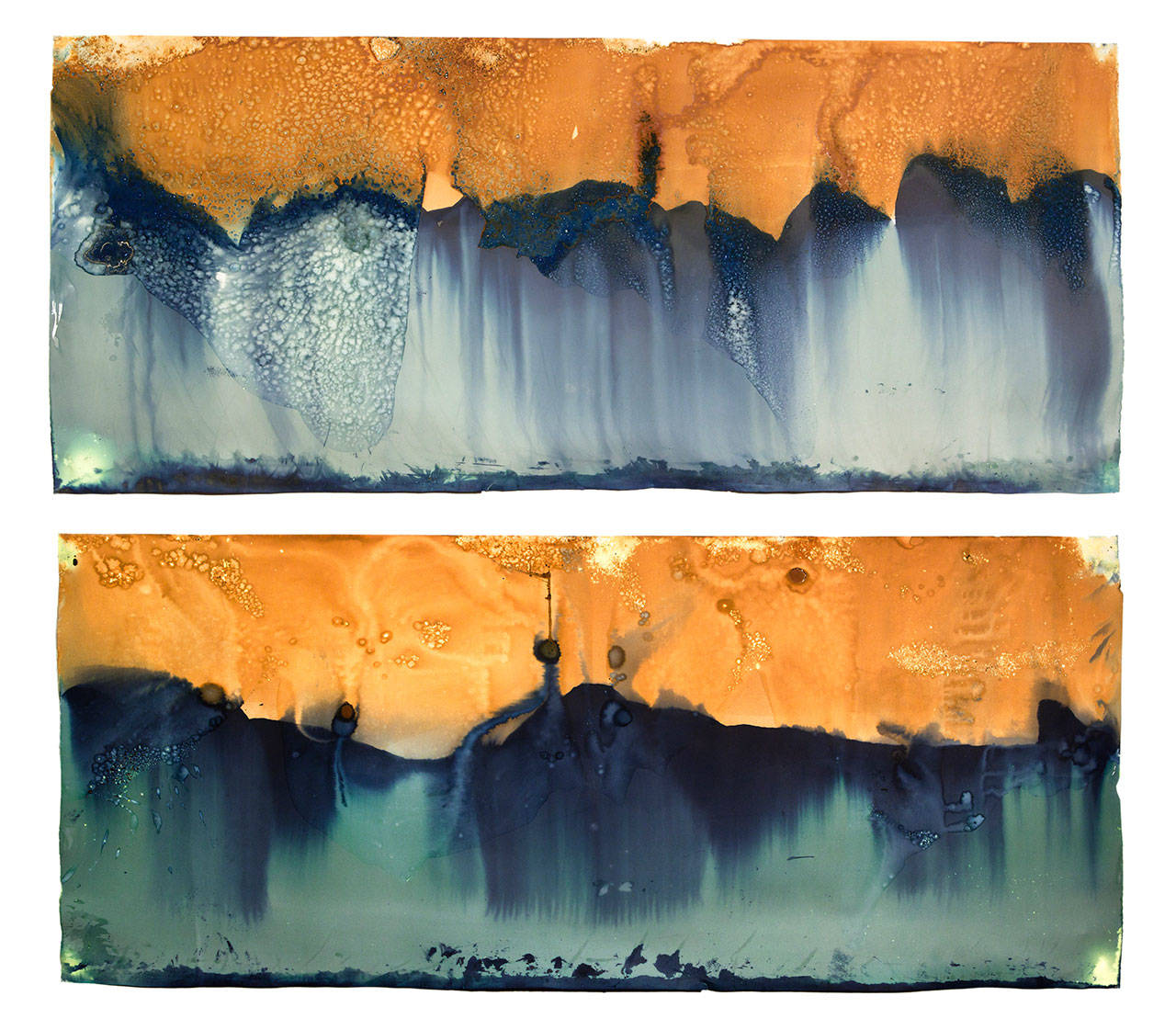

“Littoral Drift” (a geologic term describing the action of wind-driven waves transporting sand and gravel) is a series of nature-themed images made with no camera, cyanotypes created in collaboration of the sea and the shore. The elements Riepenhoff uses to create the pictures — rain, waves, sun, wind and sediment — leave actual physical inscriptions through direct contact with the photographic materials. Photochemically, the pieces are “finished” before they are wholly processed, and will continue to slowly respond and change based on whatever environment they are displayed in.

“I intentionally leave the images only partially processed,” Riepenhoff said. “They’re processed to the degree that water from the landscape hits them. Cyanotype is a really cool photo process because it only requires water to wash it, so if a lot of rain washes over an image it might actually become close to fully processed, but, if I’m in a light storm, then the image remains primarily latent chemistry and is therefore more dynamic. They change according to humidity and UV exposure.”

Cyanotype is a photographic printing process that uses just two chemicals, ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide, and no developer. It produces an iconic cyan-blue print. Though first discovered in the 1840s, engineers reportedly used the process well into the 20th century as a simple cheap way to make copies of drawings (hence the origin of the term blueprints).

Such potentially shifty work makes for an interesting problem for gallery staff, and a divergence among those who purchase the pictures, Riepenhoff said.

“Some collectors who have my work really exploit that change,” she said. “They put the piece right out in a window, not behind any plexiglass. Others really protect them and they’re hermetically sealed in dark rooms. There’s a very collaborative way that the pieces happen over time.

“For me the work is so much about dynamism and cycles and impermanence and the way that’s embedded, obviously, in the human experience, but also in the landscape,” she added. “I’ve been working on this project long enough that I expect the change; I anticipate the change. I can’t control the change, so I’m kind of open to that impermanence.”

It’s a messy, antiquated, labor-intensive process, anathema to the digital-only, selfie snappers of the world — and that’s half the point.

“The digital revolution has had some nice, I think, impact that was probably not intended, where a lot of fine art photographers are now going back and working with these antiquated processes and these antiquated materials and just sort of discovering the roots of photography again,” Riepenhoff said.

The other half of the point, of course, is the subject itself. The water and the shore have as much impact on the image as any decision Riepenhoff might make. Receiving the Guggenheim Fellowship, she said, will enable her to focus her work on areas in most need of attention.

“I’m going to be shifting the way that I’ll be selecting bodies of water for the next year and we’ll be printing in a more targeted way, with water issues at the forefront of the conversation,” she said. “I’ve been working in bodies of water all around the globe, just depending on where I find myself, and the proposal was specifically to look at bodies of water who are experiencing conflict, either because of human interventions or problematic weather or because of shifts in the legislature that is going to be protecting or not protecting bodies of water from damages and pollution.”

Riepenhoff spends most of her life by the water, at work or not.

She splits her time between Bainbridge Island and San Francisco, California. Rent in San Francisco proved an insurmountable obstacle to her work needs, Riepenhoff said, but then her husband’s nonprofit was headquartered here and Bainbridge became an unexpectedly perfect new home.

“We couldn’t get the kind of studio space that I need there and we could get it here,” she said. “It’s turned out to just be an incredible place to work. It’s been totally shaping my work and I feel really fortunate.”

Though she was traveling for work when she applied for the fellowship, Riepenhoff was closer to home when she learned she’d been selected.

“I was sitting in my bedroom on Bainbridge Island, and I got an email and it was sort of like, you know how a goldfish goes around and around in a bowl and it keeps getting that excitement every time it comes around to the same thing? That’s sort of how it felt,” she said. “It was like, every couple minutes I would realize that the committee had awarded me a fellowship, and we celebrated by going to the pub.”

The Guggenheim Fellowship program is a significant source of support for artists, scholars in the humanities and social sciences, and scientific researchers. Since its establishment in 1925, the foundation has granted more than $360 million in fellowships to more than 18,000 people.

This year’s recipients were reportedly chosen from a group of nearly 3,000 applicants. In all, 49 scholarly disciplines and artistic fields, 69 different academic institutions, 31 states and three Canadian provinces are represented by this year’s class of winners, who range in age from 29 to 80.

Riepenhoff said, in addition to goldfish-type excitement, she feels “incredibly supported” in the wake of the announcement.

“Not only through the foundation but also through my community reaching out,” she said. “I heard from my framer and my elementary school boyfriend, getting to share this kind of news with my parents was kind of a dream come true. There is a way an award like this touches the entire community, and I think that ‘a rising tide lifts all boats’ feeling is very much what I’m experiencing right now. I’m just thrilled to get to share this with my people.”

The award is especially gratifying, she said, as the “Littoral Drift” project encompasses everything about photography that she first fell in love, even without the camera. It all started in high school, in a very dark room.

“There’s something about the moment that the image showed up in the developer; it was alchemy and it seemed magical,” she said. “There was this kind of really beautiful way that the developer forced the latent image, which was invisible, to reveal itself. Photography, for me, my earliest interest in it was very much in chemistry and light and the sort of alchemical nature of the materials.”

In a world overflowing with images, Riepenhoff said work like hers, work that celebrates physicality and change and actual experience, is more important than ever.

“We’re sort of relying on these immediate images to codify that something is real or that it happened,” she said. “I don’t know that we’re more visually savvy, I do know that we’re more visually inundated. This proliferation of images, I think one of the consequences of that is that people are often times substituting imagery for actual experience. It’s like if you go to a museum, it didn’t happen until you take selfie in front of the painting that you liked. There’s this way that making an image is sort of codifying the experience, or it’s saying, ‘This happened. I took an image of it.’

“I think one of the pitfalls of that way of experiencing the world is people are becoming less present, once the image is snapped the moment is done and people carry on,” she explained. “I want to generate work that asks people to slow down and to look and to be present and connected.”

Riepenhoff is also a past recipient of a Fleishhacker Foundation grant, residencies at the Banff Centre and the John Michael Kohler Arts Center, and an affiliate studio award at the Headlands Center for the Arts.

She is represented by two galleries: Euqinom Projects in San Fransisco, and Yossi Milo Gallery in New York. To learn more about her work, visit www.meghannrie penhoff.com.