Steven Fogell is usually loath to call a dramatic production “timely.” But he can’t help it. It’s election season, and Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” has immediate political relevance.

“What is real and what is not real, and what is going to happen in the future?” he said. “And who is going to be in control?”

The Bainbridge Performing Arts’ season-opener “Macbeth” begins with three witches fueling the ego of the titular character, fresh from a heroic performance on the battlefield. In the dark woods, they prophesy his rise to power, hinting that eventually he’ll be king.

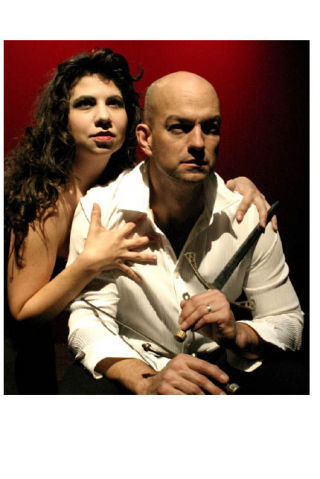

Macbeth, played by Joseph Fountain, informs his wife in a letter; she, with input from this same sinister trio, immediately begins scheming the murders that will ensure their predictions come to fruition.

Her nasty deeds beget nasty deeds, as do Macbeth’s. Nothing plays out as the ambitious couple expects, and comeuppance is had, violently.

Fogell has staged “Macbeth” many times, both for children and adults, and observed that it’s often staged to portray a man’s world.

“It tends to, I feel, play up the male characters,” he said. “And what I really want to impress upon the audience is how strong these female characters are in these productions.”

Lady Macbeth, with her treacherous agenda, is always a force to be reckoned with. But Fogell’s production puts forth an overt sensuality that magnifies intelligent, calculating feminine wiles, exploring their juxtaposition against and influence over men’s actions in the political arena.

The three witches, the Weird Sisters, have their own agenda. They play both Macbeth and his lady by planting the seed of his rise, which, like any prediction, depends on the power of suggestion as much as pre-ordained reality.

They have a fabulous time messing with both Mister and Missus, enjoying nothing so much as inducing earthy, sensuous chaos through their prediction, just as Lady M. uses her femininity – and an implied threat to her husband’s masculinity – to further her wishes.

In Shakespeare’s time, after all, women had to use what they could to get what they wanted. Their rights were limited, as were the overt measures they could take to achieve their goals. Fogell was interested in what would happen when that notion was placed in a modern context.

“How do you gain control and power? Through war, through politics, and we gain it through sexuality,” he said. “They’re all very driving forces people use to get what they want. Are they happy in the end? Well, that’s always questionable.”

Yet Fogell also regards, and treats, this politically charged play as the fantasy it is. This modern-day fairy tale approach gave him leeway to have all kinds of fun with costume, set and lighting.

For starters, he and stage manager Deirdre McCollom designed the costumes, which are period-nonspecific military for the men, proto-punk sexy for the women.

The two gathered new and vintage surplus from various branches and time periods of the military, removed all recognizable logos, took away many of the collars, and then dyed half the lot. The resulting garb sets up an instantly recognizable, anywhere-anytime militarized zone.

On the women’s front, Keridwyn Deller, as Lady M., owns her slinky negligees and industrial-flavored brocade bodices. But it’s the witches’ costumes that are characters unto themselves. With their torn lace, scary-cool fright wigs and kohl-rimmed eyes, these sisters, played by Lee Ann Hittenberger, Claire Hosterman and Valerie Anne, define an amorally earthy, punk sensibility that’s a huge treat. Think Betsey Johnson at a garden party on acid.

“Kids will see them as witches,” Fogell said. “Men will see them and think, ‘They look hot.’”

In Act II, for the scene in which the ghost of just-murderd Banquo appears and sits down for only his killer Macbeth to see, Fogell changed the usual banquet to a masked ball. This approach furthers the message of obfuscation – who sees whom? who’s hiding what? And as a playful nod to the Bard and to this particular production’s existence out of time, the attendees’ costumes are all Elizabethan. Even the witches are in costume.

“It’s unbelievable, that scene. It’s beautiful, but at the same time, it’s frightening,” Fogell said.

Adding to the sense of discomfort are the set and lighting, in part inspired by one of Fogell’s favorite theatrical ventures, Cirque du Soleil.

The stage is enclosed in a claustrophobic, murky red, and the set centerpiece is a large, half-circular platform edged with tall spikes. The bondage-y poles, Fogell said, represent both nature and industry, everything from trees to the forest to the straight Bauhaus lines of 1930s architecture.

Lighting, designed by BPA newcomer Laura Gay, plays off the set; Fogell said Gay’s fresh approach allowed him to see the familiar BPA stage in a whole new way. Shafts of light create a sinister forest when shot through the poles centerpiece; light also serves to create the suggestion of mysterious hidden rooms offstage, where yet more intrigue is no doubt occurring.

Creating this new world from scratch, especially with a centuries-old work, is part of the fun for Fogell. In essence, he said, he’s developing a genre. It’s one that he hopes will resonate with contemporary audiences, and drive home the idea that “Macbeth” is not about the past, but about decisions that lead to power structures that affect future generations.

“You have to evolve classic works like this to what is going on today; otherwise, they don’t work,” he said.