While exactly where it came from might forever remain shrouded in mystery, Chiura Obata’s untitled painting of the Topaz Japanese American Internment Camp in Utah — which somehow found its way to the Bainbridge Island Rotary Auction &Rummage Sale donation pile last year — will at last hang in a worthy home.

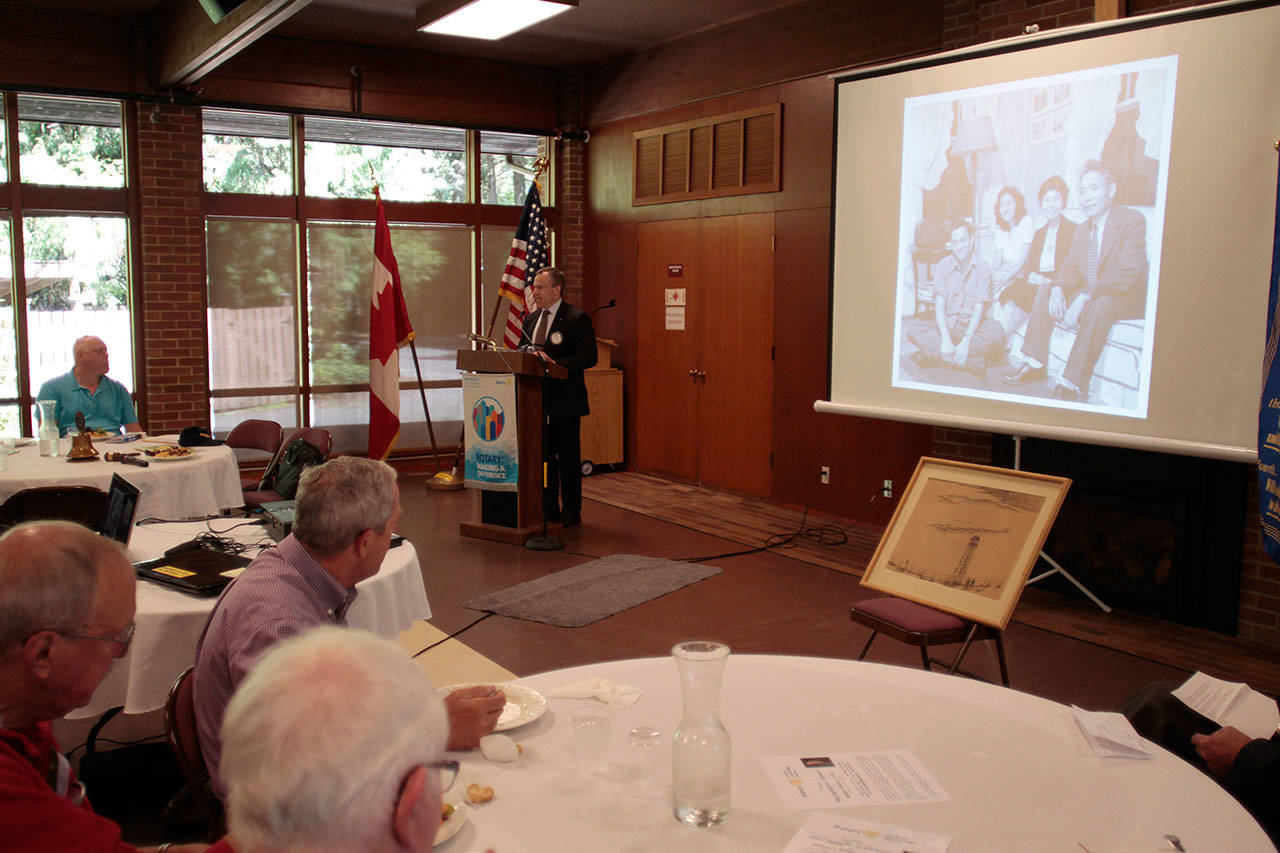

The Rotary Club of Bainbridge Island presented the painting, a monochrome mixed nihonga (new-style Japanese painting) and sumi-e style (traditional Japanese black ink painting) picture depicting the World War II-era Topaz internment camp, to Jane Beckwith at a luncheon Monday, bringing to an end this, the latest chapter in the painting’s illustrious and mysterious history. Beckwith is the director of the Topaz Museum.

“What we agreed on pretty early on was that this was not ours, not ours to sell,” Rotary Club of Bainbridge Island president Todd Tinker said at Monday’s gathering. “It was not ours to keep, that it belonged to the country and to the Japanese American community. So selling it was off the table.”

Working with the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community, Tinker said, it was also agreed equally quickly that the painting did not belong to them, either.

“They basically said to us, ‘You know what? It doesn’t belong to us either,’” Tinker said. “We obviously have here on Bainbridge Island a connection to the internment, it’s an important part of Bainbridge Island history, but this particular item was not closely associated with Bainbridge Island, and so they, in turn, helped us get in touch with its ultimate home, or where it’s going to go.”

The Topaz Museum, located at the site of the Topaz Camp in Delta, Utah, one of many relocation camps constructed for the housing of Japanese Americans in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor, is the perfect place for the painting to wind up, not only because it is the subject of the picture but also because that’s where Obata was living when he created it.

Though not, of course, by choice.

Obata (1885-1975) was a renowned Japanese artist and art professor at the University of California, Berkeley, from 1932 to 1954. His teaching career was interrupted in a big way by World War II, and he spent more than a year in internment camps.

The untitled painting was discovered to have been used as the cover for perhaps the most famous work by the renowned Dr. Dorothy Swaine Thomas, of the University of California, Berkeley: “The Spoilage.” Published in 1952, the book is a study she coauthored on the forced evacuation, detention and resettlement of West Coast Japanese Americans during and after World War II.

Finding clues

All that was pieced together by Greg Brown, an appraiser and broker specializing in fine art and antiques, who donated his time and talent to finding answers for the curious Rotarians who, though they knew it was special, had no idea what to make the of the peculiar painting that had ended up on the curb.

“The fine art team … immediately recognized it as an original,” Tinker said.

It was quite a thrill for all involved, Tinker explained, and a bit of wish fulfillment, too.

“There are many reasons why we get so many volunteers at the auction,” he said. “I think one of the factors is we’re all hoping to find some rare, hidden treasure. When you’re out there at the curb, unloading stuff, you are hoping that maybe you’re going to pull something out of there that actually has true value and meaning. Then, of course, the trick is, if something like that actually does come in, that we recognize it as such instead of accidentally giving the darn thing away on the cheap.”

The history did not disappoint.

“I looked into Dr. Thomas in association with the [original framer’s] address, and with the terms Tanforan and Topaz, the two camps where Chiura Obata, the artist, and his family had been held,” Brown, hot on the trail of some answers, wrote in his appraisal report. “I also called the University of Berkeley’s Sociology Department and from there the Bancroft Library, where Dr. Thomas’ records are kept from her internment research.

“I found out that Dr. Thomas’ work group on the internee experience, which she was the director of, [was] originally started before the internment took place by a couple of her Nisei students after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and then after the evacuation started, she chose the closest detention facilities initially, which included the Tanforan detention facility (a holding area before the internment camps were built and ready), and then expanded to try to follow them through their internment upon their transfers to their ‘permanent’ locations at the internment camps, Topaz being one of them.”

Not total strangers

Though Thomas herself had little involvement with the Topaz camp, Brown was able to find at least one place where the artist prisoner and the intrepid researcher probably crossed paths directly, long enough at least for a painting to change hands.

Tensions were running high in the Topaz camp following a dispute among internees about controversial loyalty oaths. Obata was attacked amid the mounting unrest and admitted to the camp hospital. He completed at least one known painting while there, a picture of the hospital interior, which is very similar in style to the mystery painting in question.

The painting was likely then given, or at least loaned, to Thomas, who did use it as the cover of her book (crediting Obata), but from there the trail went cold.

“I suspect … Dr. Thomas visited him there in the hospital, and asked him to do the artwork at the time based on her descriptions of the work she was conducting and the purpose thereof, which was later used as the dust jacket cover work for ‘The Spoilage,’” Brown wrote.

What happened next, though, is less certain.

Did Obata intend for Thomas to keep the painting? Did she mean to someday get it back to him and their paths just didn’t cross again? What happened to the picture next, and where has it been all this time?

How did it get to Bainbridge Island and, perhaps most importantly of all, who donated it to the Rotary?

Answers are scarce, even after Brown’s exhaustive investigation.

“The donor is unknown,” Tinker told Monday’s gathering with a shrug. “It came in … in this rush of things, and to this day we don’t know who brought in this item, despite trying to find that person.”

If pressed, Brown said he suspects it was a relative or descendant of Thomas, or a colleague, friend or student, who donated the picture to the Rotary auction, probably not knowing anything at all about it.

A prized find

Acquiring such a historical piece through such serendipitous events was a real win for the Topaz Museum, Beckwith said.

“You will always own a part of our museum, because you have made this happen,” she said Monday.

Obata’s work will fit right in among the 125 or so other works of original internment-themed art at Topaz, Beckwith said, of which about 117 were also actually made within the camp.

“We have a gallery, it only handles about 25 pieces of art at a time, but we will rotate the art that we have,” Beckwith said. “And, of course, this will provide a very prominent and wonderful story of this unusual, curbside situation that is a rather remarkable story.”