A boulder on the shores of Bainbridge Island that serves as the anchor for 3,600 years of tradition and new namesake to one of BI’s public schools could be forever changed by sea level rise.

But there’s no plan to protect the rock — partially because no one seems to know who’s in charge of it.

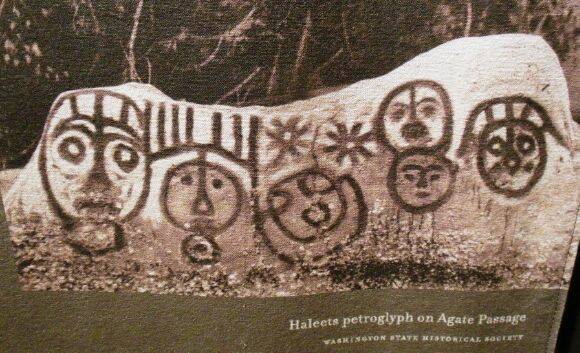

“Haleets” or ̌̌xalilc, which means “marked edge or rock” in the tribal Luhshootseed language, is a large sandstone glacial erratic at Agate Point inscribed with petroglyphs created by the Suquamish Tribe between 1600 and 1000 BCE. Standing 5 feet tall and 7 feet long, the glyphs depict several faces and geometric designs spread over the boulder’s surface facing Puget Sound waters.

While its precise original function is unknown, Indigenous archivists and archaeologists suggest that it could be a boundary marker, a welcome sign or a calendar. The stone is the first stopping point for the tribe’s annual canoe awakening ceremony, and in 2009 BI astronomers observed that a person standing in front of the boulder on the vernal or autumn equinox can witness the sunrise straight through the Skykomish canyon 60 miles to the east.

Additionally, ̌xalilc is situated very close to the original site of the Old Man House, a feat of Suquamish architectural achievement and home to both Chief Kitsap and Chief Sealth. It was the largest structure of its kind constructed in the Salish Sea: 200 feet long and 100 feet wide, almost as large as a football field. The tribal museum describes Old Man House as an “intertribal gathering place where people from all across the region came together for trade, celebrations and diplomacy.”

Researchers at the University of Oregon postulate that ̌xalilc is part of a trio of stone petroglyphs in the region, all of which were once situated on the shoreline of their respective tribal lands: Haleets; the North Bay boulder, near Allyn; and the Harstine Island boulder, now located in the Squaxin Island Tribe’s Veterans Memorial in Shelton. Each stone was initially above the high-water line but repeated earthquakes along the Seattle fault may have pushed Haleets into the intertidal zone.

Today, Haleets is regularly underwater during high tides and is covered in barnacles and other fouling. Waves have begun to wear down the rock, which obscures and conceals the ancient art inscribed on the boulder.

The Suquamish Tribe has historic ownership of the artifact and has asked the public not to disturb the barnacles lest they unintentionally damage the carvings beneath the surface. However, tribal officials state that because ̌xalilc is not on Suquamish municipal land, their hands are tied — any mitigation efforts will be up to the owners of the beach.

Typically, the Department of Natural Resources lays claim to most aquatic lands statewide, and the Department of Archaeology and Historical Preservation manages artifacts and important pieces of history. But this property is not state-owned, officials said.

Instead, ̌xalilc is on private property, which is listed under an investment portfolio called the “Main Street Endowment Fund.” That name references a state tax incentive called the Main Street Program, in which small towns in the state with historic downtowns can support the local economy by managing, promoting and recruiting new businesses and make the shopping district visually appealing.

Department officials assert that because Haleets is on private property, the agency cannot comment on Haleets or its future.