What a mixed blessing to come of age in the 1960s, a decade defined by upheaval, in which a generation of youth was forced to measure and define itself against an ever-shifting political and cultural landscape.

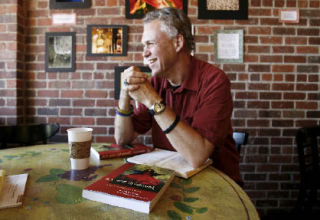

“The options for distraction and destruction were manifold,” William Cleveland said.

Making music, which stepping into analysis mode Cleveland calls an intrinsically generative process, proved to be a remedy for his own confusion about how he fit into the larger scheme of things.

Its discovery not only served to ground him personally, but also set the stage for his life’s work as a writer, teacher, community organizer and cultural activist whose world view and professional pursuits center around the notion that culture and the arts are not appetizers.

Rather, they are essential nourishment for a thriving community.

“Art and Upheaval: Artists on the World’s Frontlines,” is the island resident’s recently released fourth book, and it offers a variation on this theme.

But to understand the book’s place in the trajectory of Cleveland’s work, it’s helpful to back up to the point where he realized making music wasn’t enough; he required a stabilizing force. Enter bureaucracy.

Cavalier and facetious classification of a government agency dispensed with, Cleveland became involved at an artistic level with the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act. This U.S. Department of Labor program, enacted in 1973, offered work – largely in public agencies and nonprofits – to unemployed and underemployed individuals.

Many of those who qualified were artists. And through the program, they parlayed their talents and skills into public service.

That meant that a painter, for example, might set up classes at a local senior center. Or an actor could develop a drama program for an after-school program for low-income students.

Cleveland learned key lessons during his three years of administrative work with CETA, among them that art and public service are not mutually exclusive.

“This whole idea of bringing art into the center of everyday life needs translation,” he said. “It needs diplomats. It needs a bridge.”

And that, slowly, was how he came to define himself and his own profession, as that bridge.

Cleveland next spent 10 years with the California Department of Corrections & Rehabilitation, where he saw 12 institutions grow to 40 and alongside that explosion, helped develop the Arts-In-Corrections program, an extensive residential arts program.

“Talk about translation,” he said. “Some serious translation challenges existed.”

Yet by the end of his tenure with CDCR, the program had 25,000 active participants. Time and time again, Cleveland witnessed the hunger with which inmates absorbed the arts, bringing home once again the notion that culture is not an hors d’oeuvre; it provides essential nutrients for survival and growth, and even possesses the power to help an entire community transform itself, and transcend.

Later work at the California State Summer School for the Arts, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and Cleveland’s current venture, the Bainbridge-based Center for the Study of Art and Community, enabled Cleveland to explore these themes within different settings; subsequent books and essays illustrated and examined it in a variety of contexts, particularly in American communities and social institutions.

With “Art and Upheaval,” Cleveland expands to locales worldwide, focusing on the role of the arts not just in other countries but in areas in which political and cultural unrest has left lasting scars that in some cases still permeate day-to-day life.

The project began in 1999 when Cleveland, attending a conference in Northern Ireland, learned of a community theater project centered around the virtually taboo topic of Protestant-Catholic marriage.

He established a relationship with the theater group and arranged to track and write about the project, “The Wedding Community Play.”

Witnessing the risks taken by this dedicated troupe, which persevered in its cross-cultural mission even as the surrounding political and religious climate intensified, so affected Cleveland that he came home to the States determined to find other, similar examples.

“Lets take a look at the tragic headlines in the last 5 to 10 years,” he said to himself. “Are there artists involved in any of these things?”

After putting out email feelers to his professional network, he received no fewer than 500 possibles in the first month.

He eventually narrowed his choices to efforts generated by community members themselves, rather than by those coming in from the outside. While he discovered many admirable, even brave cultural efforts made by foreign emissaries, he felt it was of critical importance to shed light on cultural efforts that came from within.

“The people who lived there had the context of the entire span of history,” he said. “These were people who were living the troubles.”

Gaining community members’ confidence in his intentions proved challenging; as he states in the book, “It’s not that any of them lobbied to be represented, in fact, a number of them did quite a bit to discourage my entreaties.”

Among other factors, he was a white American man; therefore, “easy, quick-to-trust scenarios did not rise to the fore so quickly.”

In other cases, stories were not ready to be told. For instance, Cleveland connected with a drum and dance troupe in New Zealand comprised of refugees from the Rwandan genocide. The author traveled to New Zealand and met the troupe.

“As we began to talk,” he writes, “their initial enthusiasm for sharing their story quickly dissipated as they realized that they simply could not bear the telling.”

Eventually, in addition to Northern Ireland, Cleveland put together cultural case studies from Cambodia, South Africa, Australia, Serbia and the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, spanning a range of artistic efforts, from theater to dance to visual arts.

And to be sure, “case studies” is a far-from-accurate descriptor, as Cleveland traveled to every community, got to know its members and found himself personally involved in and changed by each story.

“Every single one of these stories is ongoing. So it’s not like, once upon a time in a land far way. It’s in the moment, it’s ongoing, it’s happening, and it continues to happen,” he said.