Jack Kutz, 90, marine surveyor and lover of boats, cast off the mooring lines of this life on Nov. 2 from a Seattle nursing home. The yard in Venice on Bainbridge Island where he lived several decades was once chock-a-block full of keelboats, sailing and rowing dinghies, and maritime flotsam and jetsam. The boats are gone now.

Jack had not lived at home most of the last few years since his polyester sweater caught fire. Diving into his luckily full bathtub of water saved him.

Several painful days later as I entered Harborview’s intensive care unit for burn victims, his eyes perked up, he smiled and began talking non-stop — about boats!

I was carrying a model of a new Tom Henderson designed sailboat for kids. Though Jack’s back had more skin grafts than some old surviving Port Madison Prams, I knew he’d survive. He was talking about boats again. Boats heal and ease pain.

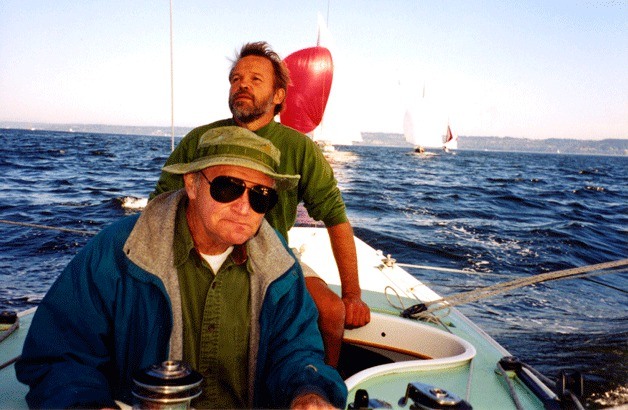

For many years he and I drove to quarterly meetings of the Pacific NW Maritime Heritage Council — reps from maritime museums, boatbuilding schools, historic ships and harbors throughout Washington, Oregon, British Columbia and Alaska. The council met on the Fraser Delta, on Columbia shores and on harbors named Gig and Eagle.

I liked meetings a cruise control away. They meant hearing Jack’s stories. He had more sea miles and barnacles than most at the round tables.

Kutz’s Tom Sawyer years were spent with buddies Bill Garden and Johnny Adams.

Jack recalled, “We spent summers in Port Madison messing around in boats. In 1934, we sailed every day, all summer long! We knew all the old sailors who jumped ship in Port Madison during the lumber mill days. We loved listening to their stories.”

More stories came during the Great Depression from fellows who lived on the Point Monroe sandspit. In the years before it was developed, theirs was an idyllic life in driftwood shacks and derelict hulls on bountiful beaches.

Once as a boy Kutz took a bus to Winslow. On board was Luke May, the nationally famous Seattle criminologist. May lived in a log cabin on “Dead Man’s Island,” a former burial ground in Port Madison. He was first to live there and renamed it “Treasure Island.”

Jack never forgot: “That day on the bus, Luke showed me a handkerchief full of gold doubloons he said he found buried on the islet.”

By the late 1930s, Adams, Garden and Kutz spent summers farther north to fish, camp and find work among the San Juan Islands. Jack and Johnny’s first job after high school was at Winslow Shipyard.

Hired by Seattle YC Commodore and yard owner Capt. James Griffith, Kutz’s first assignment was to sort the old ships’ drawings from Hall Brothers’ Shipyard still in the yard’s vault. Jack and John met master wooden ship builder, Charlie Taylor, too. The lads were in heaven though it broke their hearts to see old wooden lifeboats destroyed that could have made cruising boats for friends or themselves!

During World War II, Jack served on Patrol Torpedo (PT) boats. Johnny captained Navy landing craft.

They were none too soon back on Puget Sound where Jack married Ruth, raised a family and worked busily as a marine surveyor often commuting to Seattle with fellow Port Madison boaters.

They formed “Port Madison Jib and Jug Association.” It became a family-oriented “Port Madison YC.” Jack and John were among the founders. Bill Garden helped designed the Port Madison Pram. Charlie Taylor built the first fleet. Ruth, among the founders of Bainbridge Arts & Crafts, saw her burgee design chosen for PMYC. It flew on Ocean, Kutzs’ sloop.

Few knew boats of all types as did Jack.

One of the smallest he took an interest in was a 100-plus-year-old rowboat once owned by Fred Grow, son of Eagle Harbor pioneers. Jack drew plans from the original so Eagledale’s Al Glaser (who Jack described as “the world’s best plywood boat builder”) could replicate the classic, stable and easy-rowing boat in plywood.

In contrast, Jack was sent to Fairbanks, Alaska, with a $2 million budget and directed Eskimo and other craftsmen who restored the National Historic Registered Nanana, the last Yukon Riverboat. He was also flown to Dutch Harbor where for days he crawled under and through a floating cannery — the iconic 1935 streamlined, art deco former ferry, Kalakala. Kutz determined she was fit to be towed to Seattle across the Gulf of Alaska. She did so.

Jack did much more and passed his love of wooden boats to many. Locally he had the highest respect for master shipwrights Andy Goodwin, Ron Keyes and the late Ed Lamberson.

Bill Garden became one of our region’s legendary boat designers; Johnny W. (as in “Waterfront”) Adams became architect for Ivar Haglund and designed shoreline projects throughout the region; and Jack Kutz kept boats afloat — three kids messing around in boats!

Boat wakes from these sailors are long-lasting. Thank you, Jack, and smooth sailing!