As the nation grapples with the continual systemic issues of racial injustice and police brutality, recently magnified by the death of George Floyd on May 25 while in Minneapolis police custody, it can become tiresome for many of us to wonder and hope when we will all, as a whole, be treated with dignity and respect in the land of the free.

Our country has seen this episode and heard this song too many times to repeat again. So, with nationwide protests and calls for change once again echoing across America, let’s reflect on some of the important protest songs that still stand the test of time in today’s social climate.

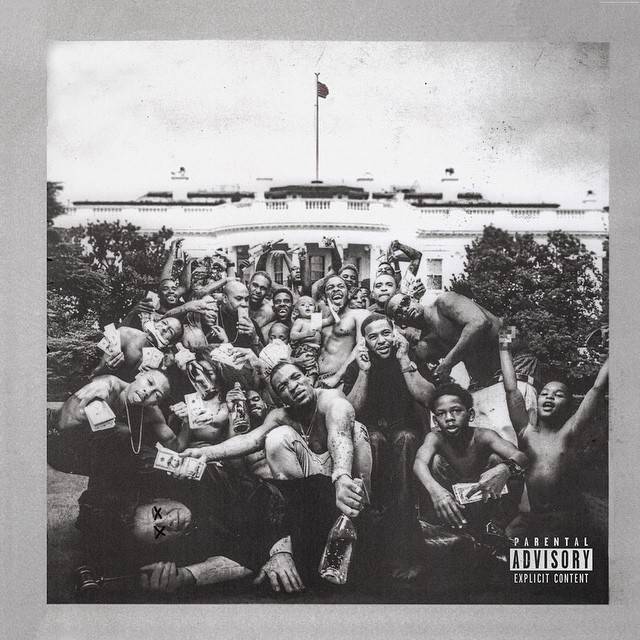

Alright

Kendrick Lamar (2015)

This protest song is a more recent track that has been heavily associated with the Black Lives Matter movement, where several protests across the country could be heard chanting the chorus “we gon’ be alright, we gon’ be alright.”

In 2019, it was named the best song of the 2010s by Pitchfork and also won two Grammy awards in 2016 for Best Rap Performance and Best Rap Song.

Lamar stands out as one of the best new hip hop artists, often articulating his past experience with poverty and racial injustice as a microcosm of greater issues surrounding injustices in America.

Ohio

Crosby Stills, Nash & Young (1970)

It’s crazy to think that this song is now 50 years old, but its message and lyrical content remains as fresh as ever.

Written by legendary renegade folk singer/songwriter Neil Young and performed by CSNY, the track refers to the Kent State shootings that same year, where 13 unarmed students were shot by the Ohio National Guard, leaving four dead. The students were shot while peacefully protesting the expansion of U.S. forces into neutral Cambodia during the Vietnam War. While the rally at Kent State was centered around the war, the escalating involvement of police in protests currently across the country and the use of force by authorities during these protests remain reminiscent of what happened 50 years ago.

At the time, Young’s songwriting was considered by many as incredibly brave with the chorus repeating “four dead in Ohio” and referencing President Richard Nixon in one of the verses singing “tin soldiers and Nixon’s coming.”

An article from The Guardian in 2010 called the song the “greatest protest record.”

Redemption Song

Bob Marley (1980)

From one of the founders of spiritual music, this was the final track on Bob Marley and the Wailers 12th studio album “Uprising.” At the time Marley wrote this song he had already been diagnosed with cancer which ended up taking his life a few years later.

The song is strictly a solo acoustic recording with Marley’s guitar playing and singing as the only components of the track. Delving into the song lyrics, it urges those to “emancipate yourself from mental slavery,” and mentions that “none but ourselves can free our mind,” two lines that were taken from Jamaican political activist Marcus Garvey at a church in Sydney, Nova Scotia during October of 1937.

Marley’s voice in this song showcases his true desire and plea for a more just world for all. Take a few minutes to go back and listen to this timeless track again and notice how much of what he’s saying still applies to the world today.

What’s Going On

Marvin Gaye (1971)

A soulful track performed by one of music’s most majestic voices has quite the backstory for how it came to be.

The song was actually inspired by fellow Motown musician Renaldo “Obie” Benson who was a member of the Four Tops. Benson cites witnessing police brutality and violence in Berkeley, Calif., during an anti-war protest, later referred to as “Bloody Thursday.” Benson then presented the song to Gaye who tweaked the melody and added some of his own lyrics, inspired by the 1965 Watts riot in California.

The song was an instant hit and with an even harder-hitting message that served as a soulful cry for peace, love and equity. Gaye was quoted as saying, “With the world exploding around me, how am I supposed to keep singing love songs?” This song almost never came to be, as Motown Founder Barry Gordy was extremely hesitant to release the protest track, fearing backlash from the government.

The Message

Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five (1982)

Coming out of the early 80s, this pioneer hip hop song was one of the first of its genre to focus on the social commentary and hardships of inner-city East Coast life for African Americans.

At a time when hip hop was primarily focused on mixing and scratching discs, this song put lyrical content at the forefront and painted a picture of everyday life in New York City. Lyrics such as “it’s like a jungle sometimes, it makes me wonder how I keep from going under” and “don’t push me cause I’m close to the edge, I’m trying not to lose my head,” resonated with listeners.

For a hip hop song such as this to come out in 1982 speaks volumes to the vision the group, which pushed forward prevalent issues that weren’t typically focused on at the time within the genre. This monumental hip hop song was ranked number 51 on Rolling Stone’s list of 500 Greatest Songs of All Time, published in 2004. The influences of this track are obvious in many of the hip hop groups and artists that would follow in the early 90s, who began to also focus on social justice and systemic hardships within the black community.

Killing in the Name of

Rage Against the Machine (1992)

There’s probably few songs that are more appropriate to fill this last spot on the list.

This band merged hip hop and hard rock to make some of the most influential revolutionary political songs in U.S. history. This particular song is arguably the group’s most popular, as its straightforward, blunt lyrics on racial injustice and police brutality are hard to avoid and get their point across quite clearly.

The song also has an angry tone with matched with thrashing melodies and screeching guitar solos by Tom Morello, befitting the intended message of the song. The basis of the meaning centers around U.S. police being involved in white supremacist organizations, such as the Ku Klux Klan, hence the lyrics “some of those who work forces are the same that burn crosses.”

The song was released six months after the Los Angeles riots which ensued after four white Los Angeles police officers were acquitted for beating Rodney King.