Midway through a question on conversation topics, he said it.

“I don’t know. I’m boring.”

Said the student who got arrested in Ferguson.

The pastor who wrestles with evangelism.

The 26-year-old among the retired masses.

Clearly very boring.

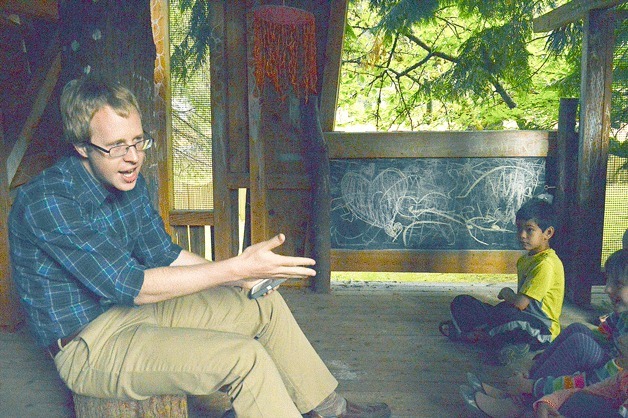

Colin Cushman, who was born in Kent, has a contentious relationship with the word “calling.” He didn’t fall off a horse, shield his eyes from blinding light and (bam!) run straight to seminary. He had a discernment process. His freshman year at Willamette, he decided theology school sounded interesting. He wanted to help people make sense of their religion responsively, avoiding “the death and destruction and despair” it had brought over the centuries.

Cushman moved to Boston and started working as the music minister at a Baptist church in Jamaica Plain; a poor, colorful neighborhood that was actively gentrifying. He played the djembe, attended open mic nights for urban youth and became close with the assistant pastor, a community organizer named Osagyefo Sekou who had grown up in St. Louis.

An urgent message

Two days after Michael Brown was shot by a police officer in Ferguson, Sekou got a text. “You need to come down; your community’s in crisis,” Cushman remembered it said. The assistant pastor, who belonged to the Fellowship of Reconciliation, began training protesters in earnest.

In October, Cushman joined him, planning to participate in a clergy action. He would enter the Ferguson Police Department and ask its chief why the force had been killing black men.

The action was merely symbolic, but Cushman and others hoped it would help to reframe the narrative. They wanted people to understand that the injustice was not just a social issue, but also a theological one.

“What we do with our bodies and others’ bodies, who we see as worthy of life, how we deal with violence — these are theological issues,” Cushman explained.

The clergy were not able to confront the police chief because of a blockade his men had set up in front of the station. There were countless protesters, and they were trying to keep them contained.

Cushman slipped through the line, only to be arrested.

“Interestingly, I do not actually remember the charges that I was brought up on,” he said. “It was originally ‘assaulting an officer,’ but because I made no contact, they changed the charges during booking.”

After six hours, he was free to go — the charges had been dropped altogether, though others weren’t as lucky.

Lessons from the front line

Cushman’s time with the Ferguson organizers was formative. He had read Paulo Freire in college and understood that both the oppressed and the oppressor were dehumanized.

But he also saw that white guilt often led to white paralysis. People were either blissfully ignorant and passively racist or enlightened and overwhelmed.

“Once you got educated, it was like, ‘Oh crap! What do I actually do?’ Because everything’s a minefield, and I didn’t know I was racist, and I don’t conceive this as being racist,’” Cushman explained.

The organizers had an answer for him: the struggle was the liberation. Or in Biblical terms: Work out your salvation in fear and trembling.

“Your salvation is something you work toward and never finish,” Cushman said. “So you’re distracting yourself from internalizing racism and supporting racism by engaging in the work and fighting it. And in joining the fight, you begin to become free.”

With his social justice commitments, Cushman hoped his first post with the United Methodist Church would be in an urban community. The placement at Seabold looked like the opposite. But not without good challenge, Cushman decided.

He studied the demographics and learned some interesting things: Bainbridge has 9 percent people of color, 6 percent of people below the poverty line. “It’s like, ‘Where the heck are they?’” he said.

He’s also intrigued by the dynamic with the Kitsap Peninsula.

“The folks on the island seem to identify themselves closely with Seattle, to the degree that everybody else in the Kitsap Peninsula is in the Tacoma district of the church, and we have insisted that we stay in the Seattle district, even though we’re the only ones on this side of the water.

“It’s an interesting relationship because we go into Seattle for work, and we identify ourselves there, but we don’t have the Seattle problems. Versus, oh hey, a mile north of us is this Indian tribe that we have virtually no connection to. We’re completely disconnected.”

That question, of “Who is my neighbor?” is something Cushman wants to take on and stretch in his tenure, which could be two or five or 10 years, depending on how good he is and where else he might be needed. His parishioners, who hail from Indianola, Kingston and Suquamish, keep him steeped in off-island needs.

Plans in the making

One population that Cushman is determined to reach is the LGBTQ community. Seabold decided in 2014 that it would be an all-inclusive church: “We celebrate the sexuality and spirituality of all persons,” they declared in a press release.

That decision, Cushman said, has been touched upon but not publicized much. He wants everyone to know where the church stands.

Cushman’s immediate to-do list takes up three sheets, not to be confused with “Short-Term” and “1 Year (July 2017),” which are also posted with thick beige tape on his office wall. It has items like “set up Google Voice for pastoral care emergencies” and “intentional prayer ministry (see notes),” which makes you wonder how many other piles of notes there could be.

No doubt, this guy is organized. And hopefully, a Costco member, getting a discount on all the blue and yellow stickies he’s plastered on his sermon wall. He’s scribbled headings like “Texts of Terror” and “New Beginnings” (which was his first series, based on the passage in Luke when Jesus reads a scroll from Isaiah: “God has anointed me to bring relief to the poor, sight to the blind, etc. and proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor,” Cushman paraphrases).

He added, “If that’s what Jesus is setting as the main focus of his life, that’s what we should be focused on, too.”