Rolling Bay and Lynwood are the most likely spots for retail marijuana shops to take root, the Bainbridge’s community planning chief told the city council this week.

The Bainbridge Island City Council dug into the nitty gritty of the new Washington legal marijuana law at this week’s council meeting.

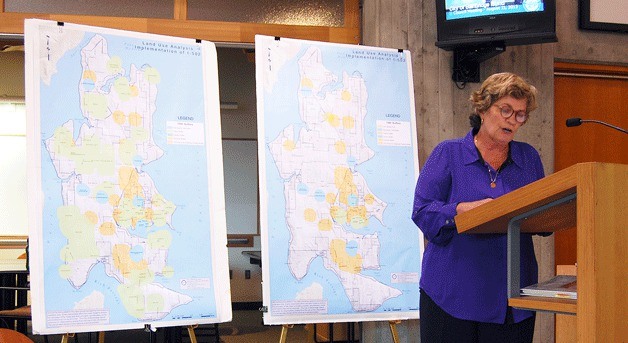

Planning Director Kathy Cook gave an overview of how the city can implement zoning policies for licensed marijuana businesses.

Cook also told the council that while most of the property on the island would allow agriculture and greenhouses under the existing residential zoning, legal marijuana grow operations won’t sprout up everywhere.

That’s in part because of a 1,000-foot “no-go” areas for marijuana operations and regulations that dictate properties with marijuana grows have farming as a primary use.

The council made no decisions on potential city regulations on marijuana businesses this week, and will continue to study the issues involved at its next meeting.

One island resident, however, noted the city’s response to an application for a medical marijuana business last year. It was an example that the city was unprepared to deal with legal marijuana.

Aston Reeder said a friend had submitted a business application for a medical marijuana operation that was denied.

“I certainly hope that we get more people applying for apothecary shops,” Reeder said.

“The good that it does sick, hurt, dying and elderly Americans is extraordinary,” he said. “It’s time that we get that kind of resource for the people here who need it.”

City officials are now grappling with regulations that will be needed to handle the recreational use of marijuana, a complex undertaking since marijuana remains illegal under federal law.

In November 2012, Washington voters passed I-502, the marijuana legalization initiative, which allows state government to regulate and tax adult marijuana use.

To enforce the new regulations, the state has divided the budding industry into three parts: marijuana producers (growing the plant); processors (incorporating the plant into edibles, liquids or packaged bud for retail); and retailers (the actual shops where marijuana can be purchased).

The state Liquor Control Board developed the basic guidelines for the law’s implementation this summer. The schedule for carrying out the new policy requires the rules to be adopted by cities on Sept. 4. This will be followed by a 30-day period for business license applications to be submitted to the board from Nov. 18 to Dec. 18.

With this timeline, the city council was advised to have an ordinance in place by mid-December to help organize licensed businesses.

At Wednesday’s meeting council members centered in on how the three components of marijuana business would be defined by the city’s code and where Bainbridge Islanders can expect to see pot businesses popping up.

According to the land-use provision included in the initiative, the state Liquor Control Board cannot issue a marijuana business license for any operation within 1,000 feet of elementary or secondary schools, playgrounds, recreation centers or facilities, child care centers, public parks, public transit centers, libraries or game arcade locations.

Cook provided a map this week that displayed all of the no-go zones of the island where licensing will be restricted according to the 1,000-foot rule.

She then explained how each of the three components of marijuana business will be affected by the city’s development regulations.

Since a marijuana grow operation meets the definition of crop agriculture for the city, Cook set out the ground rules for agricultural activities on the island.

According to the city code, crop agriculture is permitted in all residential zones, including the higher density areas surrounding downtown. The code also encompasses the use of greenhouses on a property.

“Our city is about 96 percent residentially zoned, so the amount of residential zoning that could potentially support a growing operation is pretty significant,” Cook said.

The Liquor Control Board prohibits marijuana production from being conducted in a personal residence, however.

For a grow operation to comply with the regulation, Cook explained, the agricultural business must be the primary use of the licensed property and describe itself as a working farm despite being in a residential zone.

The second component of marijuana business was identified by the planning committee as agricultural processing. This includes the commercial preparation and manufacturing of crops.

The city’s zoning code permits manufacturing in the business industrial districts and the High School Road districts, explained Cook. When again taking into account the 1,000-foot rule, it limits the potential for new pot enterprises to the east side of High School Road.

On the retail end, the city’s main commercial areas are High School Road and the downtown center.

Like the first two components to marijuana business, much of the downtown area and High School Road is impacted by the 1,000-foot rule with the nearby parks, schools and recreational centers.

That leaves essentially two more options, Cook said.

Rolling Bay and Lynwood Center remain mostly unencumbered by the restrictions and are likely locations for retail, she said.

In the council’s next study session, they will receive clarification from the planning committee on restrictions for the use of city-owned farmland; how the city can respond if a park or childcare facility is constructed in close proximity to an already-existing marijuana-licensed business; how the Liquor Control Board’s residential zone regulations and the city’s own agricultural regulations overlay; and how regulations on medical marijuana can be incorporated.

Leading up to the establishment of an ordinance, the council will also look at putting in place interim regulations modeled on templates established through Municipal Research Services and other cities.