Proponents of Proposition 1 say it will fund much needed roadside improvements for bicyclists across the island, give children safe routes to school and pay for new sidewalks for pedestrians.

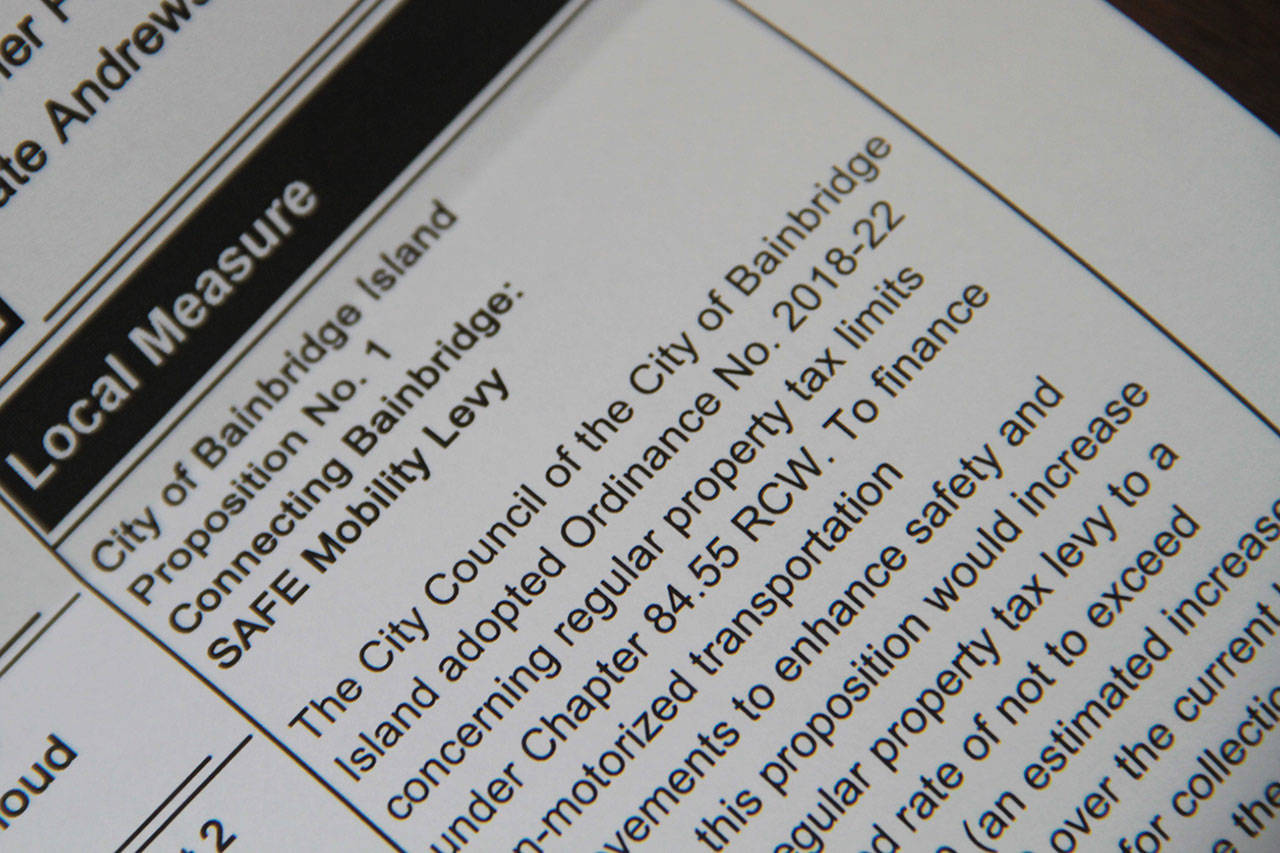

Critics of Prop. 1 — the city of Bainbridge Island’s $15 million, seven-year property tax levy — say it’s a costly boondoggle that will mostly benefit Bainbridge’s small-but-vocal population of bikers, and will saddle island property owners with yet another tax increase.

Prop. 1 supporters say the roadside improvements will encourage more people to get out of their cars and walk or bike, which could help reduce carbon emissions and climate change.

Opponents, however, say the ballot measure doesn’t spell out which improvement projects will actually be built, and note the city’s spotty history on non-motorized projects, including the controversial tree clearing for the first leg of the Sound to Olympics Trail and its now-abandoned “Bridge to Nowhere” on Highway 305.

Prop. 1 needs a simple majority to pass, and voters will decide during the General Election Nov. 6 if the levy moves forward.

If approved by voters, the ballot measure will raise property taxes by 28 cents per $1,000 of assessed property value, according to a city estimate. For the owner of a $660,000 (the median home value

on Bainbridge), the property tax bill will rise by $185.

“The levy isn’t mainly for people currently biking and walking (though it will certainly help those people) — it’s for the big group who are now ‘on the sidelines’ because they don’t feel safe biking and walking in many parts of the island,” said Demi Allen, a board member for Squeaky Wheels, the island’s bicycle advocacy group, and a member of the city’s Multi-Modal Transportation Advisory Committee.

“Researchers have called this the ‘interested but concerned’ group — and it tends to be large. We want those people to have a real choice to bike or walk when that works for them,” he said.

Critics have blasted Prop. 1 because it doesn’t guarantee a set list of specific projects.

But Allen said Bainbridge does have an islandwide transportation plan and a list of needed non-motorized projects.

“That’s the starting point for the discussion of which projects get built,” he said.

The worry about not including a project list in the proposition also extended to the city council, and Prop. 1 failed to get majority support from the council until the city agreed to set up a SAFE Mobility Project Selection Committee; a group which would help guide the community discussion of which projects would actually be built should the levy be passed. The group will include council members, representatives of the school and park districts, members of the city’s Multi-Modal Transportation Advisory Committee, and 15 other island residents.

While the ballot measure doesn’t include a project list, officials have said the levy will be split into four sections, with 45 percent of the funding going toward roadside shoulder improvements, 30 percent devoted to trails with a focus on safe routes to schools, 15 percent for better connected sidewalks in the Winslow core, and 10 percent for other project opportunities that come up during the next seven years.

Doug Rauh, who authored the statement against Prop. 1 in the county voters’ guide, said Prop. 1 will hurt residents more than it will help.

Property owners have endured a constant stream of tax increases, he noted, and another one — a $15 million measure for school improvements — is coming on the February ballot. There’s also uncertainty about the economy, Rauh said.

“When is enough, enough?” Rauh asked.

“With the large number of islanders being over 50, and many of them living on fixed incomes, we probably need to slow down a bit right now,” he said.

Though the levy is being marketed as a safety measure, Rauh said, widening shoulders on many roads may have the opposite effect.

Studies have shown that drivers tend to go faster on wide roads because they feel more comfortable, and Bainbridge’s narrow roads tend to make drivers go slower, he said.

“They drive their comfort level. If you widen the road, they go faster,” Rauh said. “It’s not going to make it any safer.”

There are already many areas on the island where people can walk and bike safely, he added.

“The parks department already has 32 miles of soft-surface trails; trails that are not next to a road,” Rauh said.

Allen, though, said the levy would fill a needed gap in funding for non-motorized projects for an island that has long talked about improvements for bikers and walkers.

“We want safe facilities for walking and biking and the magnitude of the annual cost per household is, I think, reasonable,” Allen said.