Considering the times we live in, unity is more important than ever.

Travis Tebo, associate principal at Sakai Intermediate School, and his team are teaching students about the importance of unity. As an example, they studied how former Bainbridge Island Review newspaper owners Walt and Milly Woodward supported Japanese Americans who were interned during World War II.

Students learned about upstanders — people who stand up for others when they are down. They also wrote haikus about unity, including these fifth-graders.

This one was written by Riley Cole:

come together now

come stand by me and be brave

this is who we are.

Regarding the Woodwards’ story, Riley said she was impressed with how islanders banded together to try to stop it from happening, then also tried to help them get out of the camps.

She said she tries to be an upstander, and also appreciates when her friends do that for her.

“Unity Day means helping each other as a community, being brave and coming together,” she said.

Riley said the island is filled with upstanders. “It’s the way I feel like most people are that I know,” she said.

Here is a haiku written by Kinsley Armstrong:

little things matter

one word is all that it takes

just for each other

Kinsley said the main theme behind her poem is, “You don’t have to change the entire world, just your own.”

She said it can be as simple as saying one nice thing to someone.

“It makes their day with compliments,” she said.

Kinsley enjoys this positivity so much that she wants to do it more.“I’m more open to helping other people,” she said.

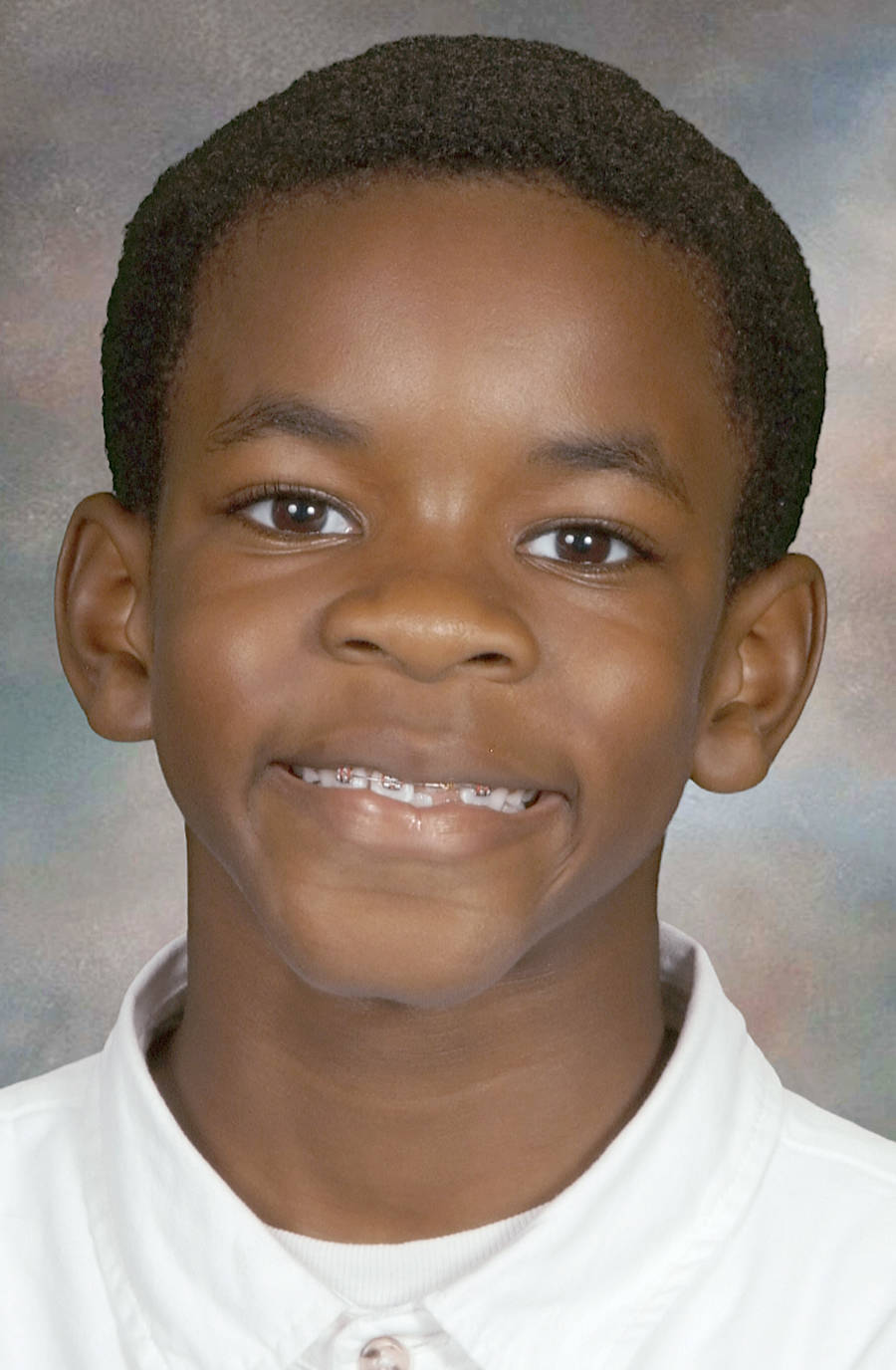

Ishmael Brown wrote this:

the flames can rise up,

or together we can rise

and blow the flame out.

Ishmael was very symbolic in his poem. By flames he meant bullies. By taking a stand together we can silence the bullies. He said he remembers once being bullied playing football when a friend stood up for him.

As for the Woodwards, he said people were afraid after the U.S. was bombed by the Japanese at Pearl Harbor. But he said that doesn’t mean the Japanese Americans living on Bainbridge Island deserved to be interned. “There was no reason; they were not a part of it,” he said.

Also using symbolism was Haven Rudnick:

like roses we bloom

in beautiful unity

Sakai here we grow

Haven said roses are the original flower of unity. She said because of COVID-19 she feels isolated since students are learning from home.

“It’s really hard right now, not seeing each other,” she said, adding it has given her a greater appreciation for being at school with classmates and even teachers. “We should celebrate Unity Day every day.”

She said it’s only normal to help people out, but it can be hard when dealing with bullies.

Haven gave an example of some older girls basically ignoring another girl at the public library. Even though the girls were older and Haven was “afraid what they might do to me” she went to the librarian, who intervened to help.

Haven said she doesn’t want to be a bystander so even if facing a bully she would find some way to help. Once, when sitting with a friend who was being picked on, she intervened with some sarcastic humor.

“It probably wasn’t the best way to handle it,” she said. “But they stopped. I used humor, but I was a little bit mean back to the bullies.”

As for the Woodwards, Haven said she was impressed; they could have easily have said of the local Japanese Americans, “Oh, well, they’re gone.” Instead, the newspaper folks brought the community together as if they were still on the island.

They made videos

A couple of high schoolers were involved in a video shown in the district to explain Unity Day.

Claire Jackson, a junior at Bainbridge High School, said when she was in middle school there was a party with some illegal stuff going on. When her mom got wind of it, she warned other parents. “She did it out of the goodness of her heart,” Claire said.

But the students didn’t appreciate it. They thought Claire told her mom. “I didn’t know about the party; I didn’t know my mom told. When I got to school everyone hated me,” Claire said.

She said others called her a snitch, she received death threats and she was beat up. She investigated and found out it was the most popular girl in school who started the rumor. Even though she was terrified, Claire said she confronted the girl, who “yelled at me and called me horrible names.” Claire said she was so thankful a teacher was an upstander and pulled her away.

Austin Smith, a senior, said bullying is something we all deal with, and people are stronger together when united.

“A bystander helps no one, and anyone can be an upstander,” he said. “United we stand, divided we fall. It’s doing something kind to someone you don’t know.”

Smith said people face hardships and may feel alone so a little encouragement goes a long way. He gave an example that a few years ago when he was at one of the lowest points of his life his good friend was there to cheer him up.

“He built up my confidence and made me laugh. He did what he could to make it better. Anyone can go through something like that.”

He said unity and being an upstander is so important right now. “This year’s been chaotic. We need every bit of brightness we can get.”

The Woodwards

Tebo explained that the story of the Woodwards is on a video.He said Unity Day explains the importance of kindness, acceptance and inclusion. An upstander is someone who sees a group being mistreated and gathers the courage to stand alongside them.

The Woodwards did that. Japanese Americans came to Bainbridge Island in the late 1800s. After Dec. 7, 1941, Americans became afraid of the Japanese because “they looked like the enemy,” he said. People on the West Coast were especially afraid because they were closest to Japan. The local defense industry feared they were next in line for attack.

Local Japanese Americans tried to show their loyalty by burning and burying everything Japanese. Despite the support of the Woodwards in the Review and many others, the FBI rounded up Japanese Americans and sent them to internment camps. So the Woodwards made reporters out of some of those who were sent away. They sent back stories about life in concentration camps so the islanders could keep in touch with their friends.

“It created community so they welcomed back neighbors rather than enemies” when they returned home from the war, Tebo said.

Unity Day

Tebo said schools in the Bainbridge Island District honor Unity Day every year during October, which is anti-bullying month. This year even though they were at home most of the students wore orange to show unity. He said that in itself showed unity because many of the students don’t usually have their video screen on so others can see them. But they did on that day.

“Online learning is too much for some kids,” Tebo said. He hopes this message of unity and community connectedness helps. “We want to reach out to the community and spread this message of togetherness,” he said. “We’re here for each other.”

He said society needs to take a tougher stand against bullying. “We’re not going to tolerate bullying and the mistreatment of people,” he said. “Show kindness and love for one another.”

Tebo said the Woodwards are a perfect example. “We once came together in support of our Japanese neighbors. We can do that now, and we should do that now. That’s who we are.”