There are three ways to maintain a piece of machinery.

You can wait until it breaks down, then fix whatever failed. You can do preventive maintenance on a time-based schedule. Or you can fix whatever is getting ready to break.

It doesn’t take the proverbial rocket scientist to figure out that the third alternative, called condition-based maintenance, is the better approach.

“With the first one, you actually have to have a breakdown, which means you’re out of service for a time,” said Mark Libby, general manager of Bainbridge-based DLI Engineering. “With time-based maintenance, you fix things that don’t need it, or fail to fix things that do.”

The problem, of course, is getting a machine to tell you when and how it needs to be fixed. Providing the answer to that question has made DLI one of Bainbridge Island’s largest private employers.

The secret, it seems, is in the vibrations. Like hula dancing, every little movement has a meaning all its own.

“The vibrations that a machine gives off tell you when the machines need to be serviced, and what part needs it,” said Allison Reese of the DLI marketing department. “It’s like the vibrations from your washing machine that let you know something’s wrong.”

The vibrations are measured with attachable leads that look a lot like what a nurse puts on your chest to take an EKG. The readings also look similar – a series of blips on an oscilloscope whose meanings are hardly self-evident.

“The brains of what we do is software,” Libby said. “We provide information, not data. The software sorts through the vibrations, picks out things that are normal or abnormal, and diagnoses what needs to be repaired.”

To program its software for a particular application, DLI will create a model of a properly functioning machine, then program what typically amounts to some 15,000 “rules” onto a credit-card sized device that can be slipped into an ordinary computer.

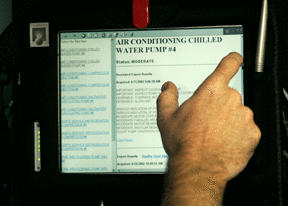

When the system is operating, it will run frequent tests on various mechanical systems, and print out the findings. So an engineer on the bridge of an aircraft carrier will know, for example, that a pump on one of the catapults needs attention.

The system pays off, Libby said. The Navy, one of DLI’s largest customers, saved over $10 million through its $500,000 contract with DLI, Libby said.

“It’s very cost-effective, and it’s applicable to a wide variety of machines,” he said. Other applications include a 24-hour brewery, which wants to make sure its centrifuge remains up and running, and the City of Bainbridge Island, which uses DLI programs at its sewage-treatment plant.

By hooking in to the Internet, machines at remote locations may be monitored separately.

Founded in 1966 by Islanders Paul Diehl and Bertel Lundgaard, DLI began as a service company, going on-site to do its diagnostic testing. In the 1980s, the federal government wanted work done at nuclear facilities in Idaho and New York, but said DLI personnel couldn’t enter the sites, so the focus shifted to providing products and training for others to use.

The firm now has 44 employees, all but two of whom work in the old church on West Winslow Way that the firm occupies. Annual revenues are roughly $6 million said Libby, who has been with DLI for almost 20 years.

The firm is for sale, Libby said, with an announcement about new ownership likely to come in the next few weeks. But Libby does not anticipate major changes.

“We will continue to operate as an independent division here on the island,” he said. “This is where our knowledge base is located.”