I recall the first time I realized my mother was not the 35-year-old school teacher that I always knew.

I’d stopped by her place to update her on a medical appointment I had, a follow-up to my back surgery. She asked how my hip was doing.

In that moment, I knew that she had lost a couple of years, that she had confused my back surgery with a hip replacement I’d had years before.

I made some excuse and left. I sat in my car and I cried.

Experiences like this are common, says Lou-Ann Lauborough, a license clinical social worker with more than 28 years experience in geriatrics and aging issues.

And what’s at the root of them is “anticipatory grief.”

“You begin to recognize that things are changing,” Lauborough said. “You know mom won’t be like she use to be and that she can’t do the things she use to. You know that the roles are changing — that she no longer is taking care of you, but instead, you are now taking care of her.”

It’s a life transition, she said, and it signals the next phase in your loved one’s life, and in your’s.

A first step is to recognize that things are changing. Have “the talk” with your loved one is the next step.

“That talk about telling Dad he should no longer drive – it’s not easy,” Lauborough said. “When you see that physical or mental decline it is necessary.”

Making sure your aging family member has been seen by his or her physician, and getting a good diagnosis is important, she said. Determining if they have normal aging, or if they have dementia or Alzheimer’s is crucial.

“When you find things like, your loved one is falling more, or mixing up medications, that’s when you need to be able to talk to them about what’s going on,” she said.

Establishing a plan of care for them is the next step.

But just as important is taking care of yourself.

When parents and other loved ones age, often times you become the caregiver, Lauborough said.

“Self-care is something that any caregiver needs to do,” she said. “If you have friends or family, it’s important to be able to talk to them about what you are going through,” she said. “If you don’t do that, you won’t ever realize that many other people are going through similar situations.”

Reaching out to others, such as those at your church or spiritual organization, is another alternative.

“And some physicians are really good at listening and they can be helpful,” Lauborough said.

There are support groups in many communities that also can help.

“I tried that when I was caring for my mother,” Lauborough said. “The first time I just sat at the back of the room and listened. But I found myself scooting up farther and farther and really being able to talk about what I was going through. These people really understood.”

And through the group she was able to learn how others dealt with situations, and use those suggestions in her own life.

When times arise where your loved one remembers things differently than you do, or when you know they are wrong, what should you do? Lauborough suggests not getting into an argument.

“Live in their world,” she said. “Don’t ask them to live in your’s. Realize that this is really your issue, that you are asking them to remember things they can’t. What’s most important is to enjoy the present moment and just being with each other.”

If your loved one mixes up the dates, or forgets what they were suppose to do, she suggests that you don’t make a big deal of it.

“Just tell them what day it is,” she said. “Don’t make them feel like they have made a mistake.”

Remember that if your loved one is aware that they are aging, and that their mind is slipping, they, too, are frustrated and even scared.

“It’s anxiety-producing,” she said. “And that can be sad. That anxiety can lead to other physical issues. So just accept that things are changing and help them to be OK with it.”

As we age, and as we move into the caregiver role, we, too, recognize that we will someday be at the point that our loved one is now, Lauborough said.

“Really, our aging parents and loved ones are role models for us,” she said. “We are facing that we will lose our parents and at the same time we know that we, too, will face death some day.

“This end-of-life time makes us think about the purpose of life and we have to come to terms with that. Those are very deep issues.”

Those with spiritual influences seem to do better with death, she added.

Lou-Ann Lauborough is a private practice therapist with offices in Port Orchard and Silverdale. She has a master’s degree in social work with specialized training in aging and health care. She can be reached at lou-ann@lauborough-counseling.com.

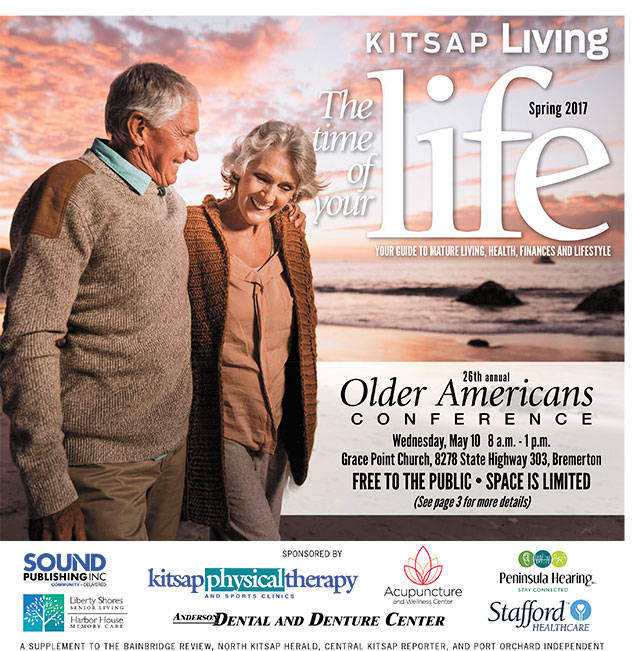

Leslie Kelly is special sections editor for Kitsap Living and the Kitsap News Group. This story first appeared in the Spring 2017 edition of Kitsap Living: The time of your life.