Editor’s note: The Bainbridge Island Rotary Club’s high school writing internship program again is having their stories published in the Bainbridge Island Review. The seven stories are on some of the community’s essential workers.

Teach me well

By Sai Kasich

The 2020-21 academic year was unlike any other. Not only was the nation affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, but so was the entire world.

After major school closures, many schools reopened in the fall of 2020. Schools implemented various techniques to keep students safe, including hybrid, in-person and remote learning. These new adjustments altered student learning, and teachers were forced to adapt. It’s important for teachers to create connections with students; that was difficult during this time. With teachers being so in demand and health risks high, teachers were stressed and overworked.

Andrew Carr is a 10th-grade chemistry teacher with a passion for his work. His teaching styles transformed online learning and created a virtual lab, making class not only fun but also educational. Carr took many different routes before finding his calling as a teacher. When he was young, Carr wanted to become an actor. He started acting in 8th grade where he played lead roles in school plays. He continued and found success as a young actor. It was his dream but all of a sudden, the passion wasn’t there. He needed to find something else.

After talking to a career counselor, he decided on going to medical school. It was there that he realized he was meant to be a teacher. He would take part in study groups and help his friends study for exams. Oftentimes he found his friends scoring better than him thanks to his help. He applied to the graduate program at the University of Washington. He was teaching a class within his first week of starting, and he felt at home in that position.

During online school, it was important to cultivate a fun environment while still being able to teach. He follows the Golden Rule – treat your students how you would want to be treated. He also says that it was important for him not to take the subject too seriously. Chemistry is hard to understand and can get boring and tedious. Keeping the mood light was crucial.

One of the difficulties Carr faced was keeping students engaged. Most students had their screens off, and Carr only felt connected to those few students who would keep their cameras on. Carr, like any teacher, was unable to gauge the receptiveness of the students.

When students started coming back in person, it was tough matching a name to a face. To Carr, up until that point his students were just names on a screen. In trying to be engaging, he harnessed a lot of tools such as virtual chemistry labs and online whiteboards.

Carr said he gets through to students by building strong relationships. He is always looking to find some common ground so that his students feel comfortable around him. Carr was always a master at cultivating curiosity on what he teaches. He “let the chemistry do the talking” and went with the flow. He always tried to hook people into his lessons and make them more “cool.” He would connect the chemistry lessons with phenomena students would see in their kitchen.

Carr was so excited to complete an entire year of in-person school. He learned how to better manage his classroom by being away from it, and it has been tough, but he loves being around his students and seeing their faces light up when they understand what they’re learning.

Check me out

By Lucy King

Michelle Swadish knows that a busy library is an indicator of a thriving community, and she’s in luck: the Bainbridge Island branch of the Kitsap Regional Library is bustling despite COVID-era changes.

As a library associate, Swadish is responsible for supporting librarians, advising readers, and organizing and distributing materials. With the onset of the pandemic, she said, “Everybody pitched in” as the library transformed from an in-person community gathering space into a series of remote operations.

One-on-one sessions with librarians, book bundles hand-selected by librarians to cater to specific interests, and the library’s massive curbside checkout operation ensured that the library achieved its goals of uniting and educating the community.

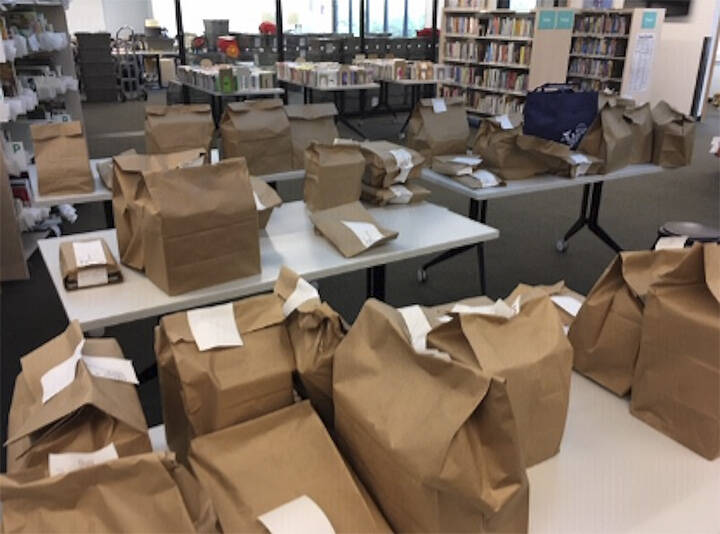

Ultimately, Swadish describes the pandemic as an opportunity for the library to “think in new, creative ways, not just for KRL but across the world.” For example, its curbside distribution system exploded from 800 materials at once to a high of over 4,000.

During the early months of the pandemic when the library offered curbside only service, holds piled up where patrons once sat. Behind that, the library’s quarantine room held stacks upon stacks of gray containers full of recently returned materials.

Despite challenges, like constantly-changing safety recommendations and the librarians’ pervasive longing for a return to patron interactions, the library community thrived, even discovering pandemic-era modifications that continue to benefit the library.

After slowly reopening in-person, the library has continued the curbside pickup option to ensure access for those who may still be uncomfortable coming inside. The book bundles have also continued, streamlining the book-finding process and introducing patrons to exciting, unfamiliar reads.

For Swadish, though, the strange new world was virtually as new to her as the library itself — the pandemic shut it down after she had worked there for only a few months. Her path to the library was long: undergraduate in anthropology at Cal State University, Fullerton, to a master’s in library sciences at San Jose State that allowed her to explore museums, archives and other libraries before finally settling on Bainbridge. After arriving on Bainbridge for her husband’s job in 2018, she fell in love with the history and “natural beauty” of the island.

Swadish credits much of her passion for library work to her past experiences. In her museum internship, she cataloged “physical artifacts, while a library catalogs information itself. Her passion for studying the past prepared her well for her current position, where she studies the present — a field she finds equally interesting but more exciting.

What drew her to make the switch was the opportunity to use her skills to contribute to the community. She looks forward to even the smallest moments with patrons, searching for that elusive book or material that lights up their faces. “People, patrons, kids, teens and adults belong in the library,” she said, which provides so much more than just books for the community. From educational materials of all kinds to the recently returned storytime events for young readers, the library offers a range of opportunities.

———

Out to nature

By Juliette-Dashe

The pandemic sucked, especially for kids. From mandated mask wearing to staying distanced to increased screen exposure, the children who have grown up in the midst of COVID-19 have missed out on developmentally major moments. The frustration for parents having to tell their child to stop playing with a friend or having to put their mask back on for the 20th time that day and cover-up is nowhere near the level of confusion and frustration the kids themselves are facing. But more recently, we’ve been able to see a glimpse of the light at the end of the tunnel.

Younger kids are able to get vaccinated, schools have been open since the beginning of the year, and the groove of childcare is once again moving along. It raises the question: what does it take to run a well-functioning program that supports, entertains and teaches a rowdy and diverse group of kids after the effects of COVID?

Zoe Vrieling, the Nature Nuts program director, said that an important aspect they focus on in their after-school and summer programs is to “kind of be that guide” and that “hopefully we can be this safe spot” to deal with the stronger emotions these children are facing after being apart for so long. Nature Nuts is an outdoor education program that provides a supportive environment for a range of ages to play in the outdoors while cultivating a love of nature.

Vrieling graduated from the University of Washington with a bachelor’s degree in environmental studies and master’s in environmental education from Miami University, but it was really when she volunteered for the Woodland Park Zoo that she found herself drawn to the education aspect of nature.

Her approach with children is to “get kids excited about a part of the environment, and hope that leads to fostering love and care for the outdoors just because they want to be outside, and they want to appreciate certain plants or wildlife.” With the challenges of climate change and the after-effects of the quarantine, Vrieling’s work should be appreciated more than ever.

“In the weeks that I have had the opportunity to work with this program, the appreciation and insight I’ve gained is invaluable. From creating an entire world of doctors who heal stuffies, presidents that arrange new election processes for the next kid who gets to have a turn, cooks that diligently prepare delicious forest concoctions, it’s not hard to see the future these children have. The most beautiful thing about it all is that they are able to connect back with nature, together. Pinecones become stethoscopes, tree stumps into podiums, flowers and leaves into inedible yet fawned over delicacies, and Vrieling’s the one nurturing their excitement for exploration.

Regarding the growth she’s seen over the years with the kids, Vrieling said: “kids become more comfortable with being outside and being wet and being dirty… just being able to kind of go through the day and be out in the rain or be out and just enjoy where they’re at. “I’ve certainly had trouble being grateful for the rain over the years, but when I see the kids jumping around and enjoying the magical water from the sky, it reminds me that it is also the reason behind the beauty of Washington.”

As to what Vrieling has learned from the kids, she said: “They’re able to kind of jump in with a whole new group of kids and be friends with them in seconds,” an ability that is lost growing up in a world of prejudice and differentiation. Other qualities from her job came up as she considered the question, each idea building on the last.

A couple of her favorite parts include that she gets to “laugh every single day. And I have a lot of fun, and it’s getting me more adventurous and…another thing we lose as we grow up. I mean, we’re always inside. We’re always sitting. And so it’s so nice to be able to indulge in the mind of a kid for a little bit.”

——————-

Light me up

By Graham Goll

As early as his high school years, David Whitbeck had always known that he wanted to be a lineman.

Thinking back to the days he’d spent in his father’s grocery store in Kingston, his earliest contact with the trade were the conversations he’d made with electrical service workers during their morning coffee runs. “I got to talking with them, and I just really liked their personalities,” he reminisced. “They seemed like my kind of guys.”

After a bit of career exploration, in particular some six months spent seeing if architecture was the right move, he quickly realized that an office job that felt so pinned to a cubicle wasn’t for him. He got his first job with Puget Sound Energy. He started out as a meter reader, but shortly thereafter picked up an apprenticeship so that he could become a lineman. Since then he’s worked in Kitsap County and in California, where he lived for a few years until he decided to return to the Northwest after the onset of COVID-19.

He is assigned to work primarily on Bainbridge, but from time to time can be called to help elsewhere. Whitbeck stressed that the priority of an electrical service worker is keeping people safe, whether that means averting the immediate hazards posed by fallen lines or circumventing the variety of consequences brought about by power outages. “It’s always a scary situation for me. I’d hate to see people get hurt.”

He talked about one instance in which a person became trapped in a car after a power line had entangled their vehicle, and he was tasked with shutting off the electricity so that firefighter would be able to safely assist the driver. Lineworkers are often at much higher risk than the general public. In many cases, the weather conditions a worker may be faced with could be so dire that they are forced to make the decision to simply wait them out.

Another story Whitbeck told of took place last winter, when he was investigating a fallen wire on the side of a road. As he was speaking on the phone with a colleague, he watched as an 80-foot tree collapsed across the street, just five yards in front of where he had parked his truck. Whitbeck’s designation as an essential worker is only magnified by his unwavering dedication to making sure the public is safe and electricity is always accessible, even when he’s off duty.

He acknowledged that there have been a number of occasions when he had by chance discovered a fallen line outside of his shift and felt obligated to take action as the first one at the scene. A lineman’s job is far from easy, but what may be even more challenging is expressing how essential they are to our safety. “Our number one priority is always the safety of the community,” Whitbeck reiterated. “It’s one thing to understand what a lineworker does, but it takes a lot more to truly understand their importance.”

———————

Vet my pet

By Isabelle McLean

How people define family says a lot about themselves and their community.

On Bainbridge Island, many include their animal companions.

Diana George, executive director at PAWS of BI and North Kitsap, is no different. She is utilizing her Fundraising Management certificate from the University of Washington and a lifetime’s worth of experience with nonprofits to uphold PAWS’ presence.

George reflects that some of her first memories are of pets, and she admits that “animals have gotten her through some long and hard times.” This ideology is one shared at PAWS and is the main contributor to the creation of the passionate and loving animal welfare community that BI has today. The same community that PAWS introduced itself to in 1975.

Since PAWS has been a vital presence in the community for just short of 50 years. They faced the same COVID whiplash as the other businesses and organizations on the island. When lockdowns hit in March 2020, PAWS faced similar but unique challenges.

Most notably, PAWS took on the challenge of caring for animals while their owners battled COVID, as an extension of their Safe Harbor program. The program provides emergency boarding for families in crisis. Additionally, PAWS now has a special card you can carry to alert emergency contacts that an animal is in the house and needs to be cared for if its owner is ill or in an accident.

While lockdowns were hard on all of us, seniors experienced an incredibly challenging time, George said, adding, “Animals are their lifeline.” Through the PAWS Vet Assist program, Pets and Loving Seniors, community members can get care for their pets in times of need.

Helping people set up with online accounts from websites like Chewy.com can help housebound pet owners get the supplies their pets need delivered to their door. As long as they can feed, walk and maintain a litter box PAWS can handle the rest. It presents a “win-win” for cats not likely to be adopted due to their age and for seniors who want to enjoy the companionship of a pet, George said.

She said the hardest thing about adoptions during COVID was “the six-foot rule.” People sought companionship but many veterinary clinics closed or reduced hours. Not only did adoptions shift to “appointment only,” it became a challenge to provide spay and neuter services; something PAWS routinely does.

Nevertheless, PAWS doubled down on its efforts. They scrambled to meet the demand via online resources such as Pet Finder and updated databases and spreadsheets with adoptable pets. And while George has noted, “a big increase in the feral cat population from the pandemic,” as a concerning trend, the massive spike in adoptions outweighs that setback, she added.

In April and May, especially, adoptions skyrocketed. PAWS was overjoyed. The response to animals with minor medical conditions, animals they never thought would be taken home, was still “…yes, I’ll take them.” Additionally, PAWS works with their animals to make them ready for adoption. That includes medical and behavioral treatments.

When asked if PAWS was worried about people returning pets after the pandemic? George said, “No, not on Bainbridge Island. This is a very generous, loving community that is very animal-centric, and many homes are two pet households.” PAWS is looking for volunteers who love working with animals. “We are a very different program,” said George, adding, “unique in that we are not in and out. We are about establishing connections.”

————————-

Keep us safe

By Johan Coe

Working at the fire station is unpredictable. At a moment’s notice, Bainbridge Island firefighters may have to answer a call. Whether it’s a fire or a medical emergency, the team is on its way.

Allen Turnbull works primarily as a paramedic who can perform emergency medical care to patients and safely deliver them to a hospital for additional care. He is also a firefighter and will fill that role if needed. When Turnbull was in middle school he had an experience where a family member needed medical assistance. Within minutes, a volunteer had provided help. Turnbull said, “I believe this event may have influenced my decision to later participate with the fire department.”

And influence him it did, when he was in high school and college he worked as a volunteer firefighter. For a career, he chose chemical engineering. He ended up working in that field for eight years. But then he returned to Bainbridge and the possibility of being a firefighter. Being a firefighter would shorten his commute and give him more flexibility for other interests like fishing.

In 2005, he took the Harborview Paramedic Training program. There were lectures and hands-on work, but he said the most important part was the ride time with Seattle Fire. 10 months later, he was a paramedic. Early on at Bainbridge, he would usually be the only paramedic on duty.

Turnbull and the other firefighters arrive between 7 to 7:30 a.m. and start their shift at 8. That way, the transition between teams is smooth. They will first make sure all the equipment is running smoothly. Daily, they perform drills to prepare them for any scenario. But if there is a call they immediately respond. It may be up to three hours before they return. Then they need to restock their rig and fill out paperwork about the call. The whole process takes up a large amount of every day. Turnbull said the department, which consists of the three stations, receives an average of 11 calls per day but can sometimes go up to 20. Or they might not get any calls at all.

The calls can stack up fast, but they can handle it with teamwork between stations and fellow firefighters. He said: ”Rarely is it one call at a time. It seems like a lot of times it’s one call and then shortly thereafter another. And it’s when we start getting those calls stacked up that it starts to really stretch our resources pretty thin.” Turnbull works for two days straight at the fire station, then four days off.

During those two days, the team will respond to calls, maintain the station and train. Every night, one of them will be chosen to cook for the others. Once dinner is made they gather around and eat dinner like a family. Turnbull recalled one call at a golf course, where he arrived to find a patient in cardiac arrest. There was a group of bystanders providing excellent CPR. He said the CPR “greatly improved” the chances of a positive outcome.

Just one week later, one of those same bystanders was in a similar situation, this time in Seattle. “They once again provided excellent CPR. Both calls ended positively.”

Turnbull said, “It’s never too late to take an initial class or a refresher – you can never predict when the need may come up.” He said the most rewarding part of the job is seeing someone he’d helped after they’ve recovered. The fire station has had many cardiac arrest survivors stop by to say hi to those who helped them. “It feels great to have been able to make a difference, and to have had the training to be able to do so.”

—————

Our history

By Camille Zaro

If you’ve lived on Bainbridge Island for a while you have probably heard of the name Bill Covert.

Whether it was because he was your child’s teacher, you talked to him at the historical museum, or have seen his work all-around BI. My older sister came home from fourth grade and would say how much she loved Covert’s class: From his jokes, storytimes and the song “The Final Count Down” playing before the classroom math competition. Two years later I would find myself in the same boat, enjoying every second of the educational yet wild nature of his class.

One of my best memories was a field trip in 2015 to Suyematsu Farm, where he’d been going since 2007. He gained interest in island history when meeting Jerry Elfendahl. He was running a class for teachers focusing on island history. “Teachers all over from different schools piled into vans and went to see sights all around the island that were rich in memories and moments of the past,” Covert reflected.

In 2007 Covert took his fourth-grade class on the first trip to Suyematsu Farm and soon that would change the course of the fourth-grade social studies curriculum. “Jon Garfunkel wanted to incorporate the farm into what he called a ‘lived curriculum’ and needed a teacher willing to take a risk to see if it would work,” Covert remembered. “Soon after my class went the other classes started jumping on.” Students would get to interact with the island’s history in the present while hearing stories from community members about its past.

One of the stories Covert remembers his students loving was one from Reid Hansen. “When Mr. Hansen was a boy, he was playing down by Crystal Springs south of the Ordnance range at Keyport when he and his friends looked in the water. There floating was a dummy torpedo. Stories like these show kids how crazy and different these times were and get them engaged in island history,” Covert said.

He expressed his strong belief in storytelling and how the knowledge and connection you can gain by listening to them can pass down through generations. An example is when Covert went with Kay Sakai Nakao, Frank Kitamoto, Lilly Kodama, and Mary Woodward to visit Manzanar (a Japanese internment camp during World War II. The stories, emotions and being able to experience it at an internment camp with survivors helping him gain a unique understanding of the painful experience these survivors overcame.

With that knowledge, he was able to teach more than 26 years at Bainbridge and a total of 34 years. Now he is a board member of the BI Historical Museum. An example of his work is the hanging posters in the walkway of the ferry full of interesting snapshots of island history. Covert credited his dad, a former high school band, teacher for showing him that a tight bond with your students means everything.