Lost Valley is no longer lost. So it might need a new name.

Through a partnership of the city of Bainbridge Island, BI Metro Parks and the BI Parks Foundation, the Lost Valley will be found by many a hiker in the future. Parks will build the trails under an agreement with the city, with construction anticipated in mid-2022.

Recently, some hikers recalled nearly two decades ago trekking across the land.

“That was coming from the creek, up this way,” said Andy Maron, who served on the City Open Space Commission when “Lost Valley” first slipped into the local lexicon. “I remember jumping over that stream,” he added, indicating nearby Cooper Creek. “You didn’t have to wade it, but jump over it.”

There was no trail in those days, and Maron, fellow Open Space commissioner Connie Waddington and an ad hoc group of explorers crunched their way through thickets and clambered over fallen logs, en route to discovery. It was a grand little expedition, one of many as volunteers scouted out remote island properties for potential purchase as public open space and parks.

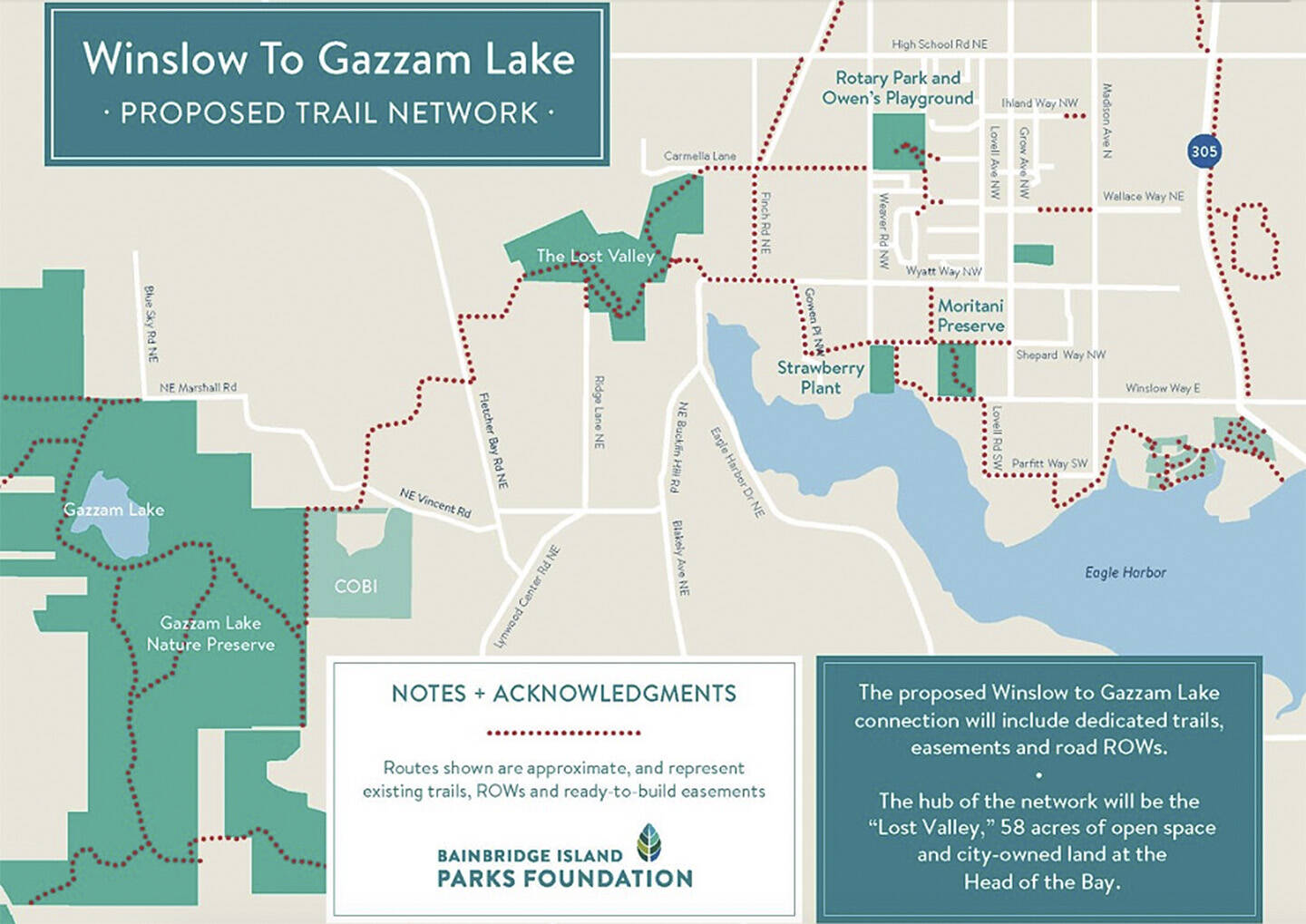

If you’re not familiar with the Lost Valley, well, consider the name. There are no formal or managed trails there, no sanctioned trailheads, no designation on any local map. Just a rough track beaten through the forest by neighbors and perhaps intrepid hikers seeking new and unfamiliar paths. It lies northwest of the Head of the Bay, closest to Wyatt Way.

As Bainbridge this month marked 30 years as an all-island city, another anniversary approaches: the 20th anniversary, next year, of the first land acquisitions under the city’s old Open Space program. Island voters in 2000 approved an $8 million Open Space bond, to protect as many large properties and create as many new parks as the money would stretch.

Over the next half-decade, the Open Space Commission identified parcels and worked with property owners to forge agreements. It was a resounding success. Acquired were: the former Wyckoff land at Bill Point, which became 50-acre Pritchard Park; created Hidden Cove, Rockaway Beach, Hawley Cove, Williams-Olson, Nutes Pond and Meigs Farm parks; added more than 100 acres and a secluded beach to Gazzam Lake Preserve; and expanded the public farmland district off Day Road.

In the middle of all that, in 2004, the city bought six acres of forestland near the Head of the Bay — roughly northwest of Ridge Lane and east of Fletcher Bay Road. It was a complicated arrangement finally involving three property owners. But when added to land the city already owned next door, the modest buy completed a contiguous, 36-acre property that would be the linchpin of a true cross-island trail.

It’s a quintessential Northwest woodland. The second-growth forest is largely unspoiled by invasives, with fields of native ferns and trees adorned with a filigree of hanging moss. The trees are so dense at points that not even the sun can find a way in.

The City Council approved the purchase in 2004, and then the Lost Valley faded back out of public consciousness. So it stayed for the next decade and a half, until plans for a cross-island trail finally began to take shape over the past few years.

Because the Lost Valley is essentially “landlocked” by private parcels on all sides, the Parks Foundation acquired a series of trail easements — legal rights of access — from neighbors at points along the planned trail route.

To the west, new connecting trails are planned to Fletcher Bay Road and around the Vincent Road transfer station. To the east, new access points and connecting trails will be planned near Finch Road and Wyatt Way.

“The Lost Valley is an integral trail link between Winslow and Gazzam Lake Park,” Mark Epstein, COBI project planning engineer, said of the trail of about 4 miles. “It will open up a contiguous route across the central island to numerous destinations.”