While Walt and Milly Woodward were busy running the Bainbridge Island Review, their oldest daughter, Mary, took note of the day-to-day family interactions that eventually shaped her life’s work.

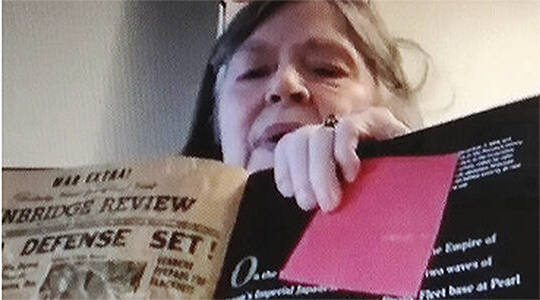

Woodward’s stories of growing up in a newspaper family are recounted through her book, “In Defense of Our Neighbors,” and recorded interviews in the BI Japanese American Community archives. Mary Woodward now lives in a senior living facility in Yakima and was unable to do an interview for health reasons.

From Woodward’s childhood perspective, a household with two newspaper editors was filled with lively dinner conversations about current events. While Walt spent much of his time at the Review, Milly cared for the children, ran the household and helped at the paper.

Woodward said she enjoyed the evening ritual of preparing dinner in the kitchen and spending time with her mother and father as they interacted.

She said her father tended to dominate the dinner conversations with topics ranging from nature to sports and current events. His daughter suspected that he was “rehearsing for the next day’s editorial.”

“I learned a lot at that family table,” Woodward says in her book.

As newspaper owners, her parents wore many hats, and Walt said they were “newspaper owners, publishers, editors, reporters, advertising salesmen, business managers, typesetters, stereotypes, printers, pressmen, mailers and janitors.”

When she visited the newspaper office, Mary Woodward feared one of the machines. “This big linotype machine always scared me growing up. It was big, and there was this big iron pot there melting lead, and it was hot and steamy.” A linotype machine created the one-time metal type used to print the paper when it was covered with ink.

Woodward spoke proudly of her parents as she remembered how they used their editorial voice to support community activities, including an abandoned well safety campaign Milly wrote about in her column. “She was very concerned that a child would get trapped in a well, so she mobilized the island people to cover their wells,” Woodward said.

It was important to her parents to cover school board and city council meetings, and “very important to them that the news articles be as objective as they could be, and that they spoke their mind in the editorials.”

They also encouraged people to write letters to the editor and “would find space for any letter that they got as long as it was signed and wasn’t libelous,” which would eventually lead to repercussions for the newspaper, Woodward said.

The Woodwards and the Review are famous for being one of the only papers in the nation to stand up for Japanese Americans during their internment in World War II. While many on BI supported that, others didn’t.

“A number of companies pulled their ads. So, there was an economic loss for them because they were really living week-to-week, and even one ad leaving was a hardship. There were a number of people who canceled their subscriptions.”

As a family, the Woodwoods attended St. Barnabas Episcopal Church, where Mary and her sisters were active in the youth choir. The highlight of each year was in August when they would get in their boat, the “Big Toot,” and go to the San Juan Islands to fish, shuck oysters and play card games.

Woodward said her parents were known for the quote, “the only newspaper in the world that cares about Bainbridge Island.” They always capitalized ‘the Island’ in the Review because it was the center of the earth…

When the BI School District named Woodward Middle School in honor of her parents, Walt said he didn’t understand why, “We just did what we thought was right.”

“My parents never thought of themselves as heroes,” their daughter said. “Walt and Milly believed in community and knew that a newspaper is what connects and ties that community together by giving a voice to the people who had no voice, by sharing the daily news of the garden club, the libraries, schools, the kids and bringing their island together.”