When Marge Williams Center tenants asked Joel Sackett if he had suggestions for art to fill the center’s conference room walls, the photographer replied, “I’m already making it.”

Sackett has been shooting islanders at home for a new exhibit, “Interior Bainbridge,” which he will show at Winslow Hardware for the November Arts Walk.

Meanwhile, Nancy Frey – as director of the Bainbridge Arts and Humanities Council, a Williams Center tenant – invited Sackett to use the building’s conference room as an extension of his studio.

“I liked the notion of Joel in that space,” Frey said, “because his work documenting people is close to the human services mission of so many of the Marge Williams Center tenants.”

As soon as he develops the photographs, Sackett hangs them – the conference room walls are becoming a timeline of the work, advancing around the room in a double row.

It’s an interesting notion, using the gallery space as an extension of the work space.

This is not a self-conscious installation piece; the photographs follow the unmediated development of Sackett’s art.

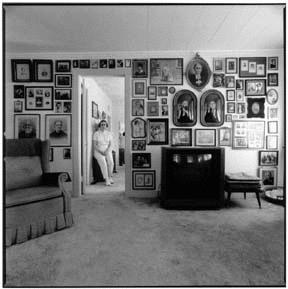

The photographs are resolutely interior. They most often contain a solitary person surrounded by his or her effects.

“I told Nancy I would put it up and spend time with them here, away from my space,” Sackett said. “I have been trying to define cultural diversity on Bainbridge in my work, and I can never quite get it. Is it lifestyle? Is it ethnocentric?

“I thought the clues could be hidden inside.”

The contrast of photos to the austere conference room is, although an arbitrary choice, a good one.

“Living in Japan gave me the awareness that people could really get into their spaces,” Sackett said. “‘Home-ism’ is the term, although I’m not sure who coined the word. These are not portraits – the people are equally weighted with the spaces.”

In some of the strongest work, it is the relationship between person and accouterments that makes the photograph.

In one, a windowless interior is hung with sepia-tint photographs in dark frames, frontal images of stern women and men bespeaking Phyllis Kupka’s interest in genealogy.

An open doorway, the only visual break in the wall pf photographs, serves to frame Kupka, standing unsmiling, hands folded at the waist, hair parted, straight and smooth.

Tim Heiner is another time traveler, but he has identified a single year and place – England in 1910.

Edwardian portraits of the royals line his walls.

Heiner is unapologetically nostalgic.

“I go off to work in Seattle,” he said, “but when I come home, I live in a parallel universe. I go back in time.”

Ross Olsen, who works at the island’s recycling center, told Sackett, “You’ve got to come over; I have a John Wayne thing happening.”

In Olsen’s space, there are photos of the Duke tall in the saddle, the Duke shooting from the hip, the Duke riding off into the sunset.

The western theme of Olsen’s interior space is underlined by touches like the cowboy hats stacked on a high shelf.

In Sackett’s photo, Olsen himself is seated on the floor.

He sheds his hated wheelchair when he is at home, he says, like someone else might slip out of an uncomfortable pair of shoes.

Viewers may enjoy seeing the complex nests some islanders construct and following an artist’s development of an idea as it unfolds.

Sackett may benefit by an increased ability to see the work fresh, removed from the accustomed venue.

Sackett’s good fortune is the result of the uncertainty of Marge Williams Center tenants about how to administer the art space.

For now, the vacuum has allowed the display of artworks whose charm may lie in their spontaneous appearance.