Some photos are forever fixed in the minds of a generation.

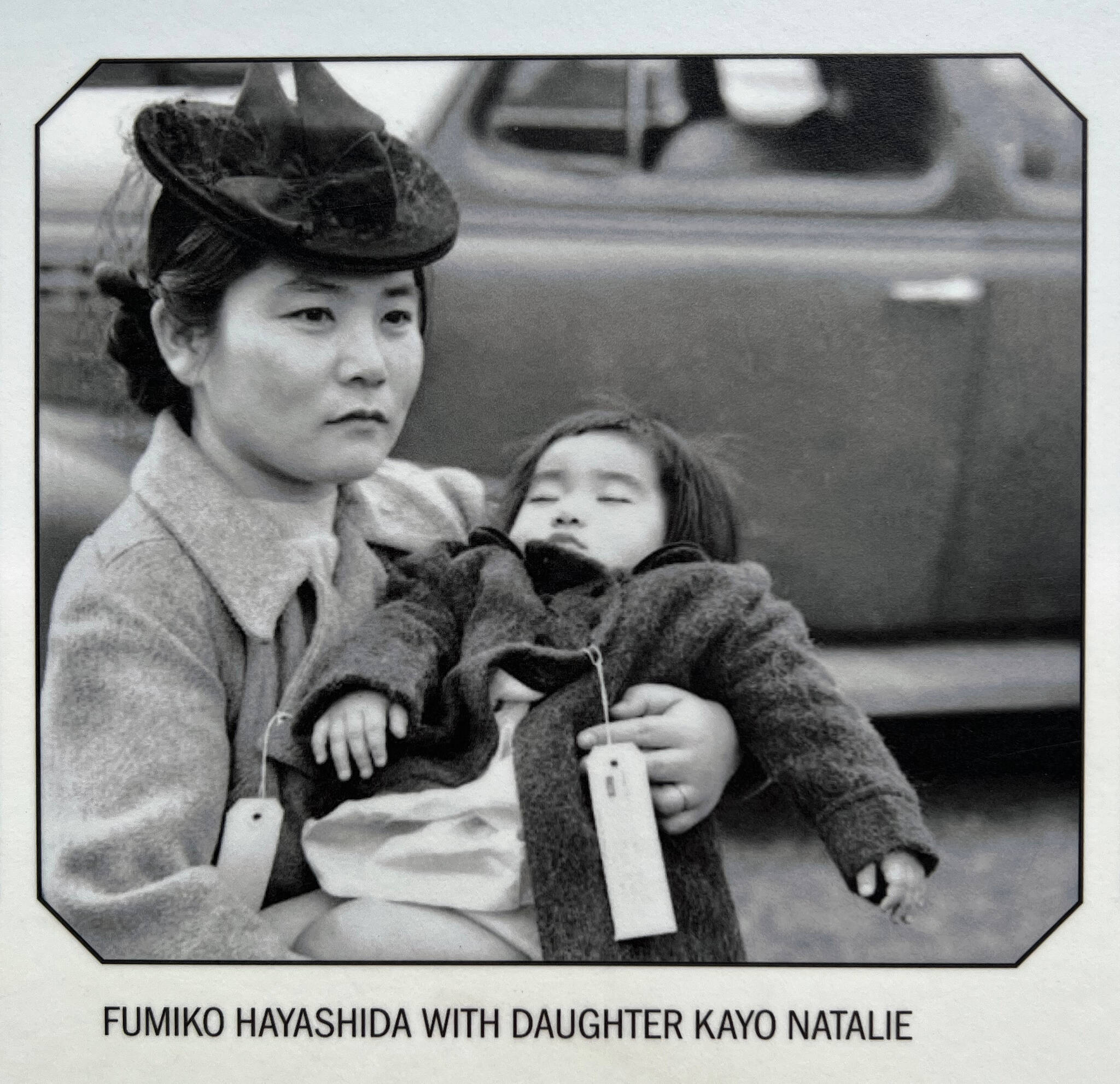

One photo of Japanese Americans assembling at the Eagledale ferry dock on March 30, 1942, featuring Fumiko Hayashida holding her 13-month-old daughter in her arms was created by a Seattle Post-Intelligencer photographer. That photo has long served as a reminder of the 276 islanders forced from their homes here eight decades ago.

In response to the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government ordered the relocation of people of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast, including U.S. citizens, to be incarcerated in internment camps. Bainbridge Island was the site of the first relocation of Japanese Americans living in Washington.

For more than three and a half years, the Hayashida family lived in Camp Manzanar in California and Camp Minidoka in Idaho.

Today, “the baby” is 81-year-old Kayo Natalie Hayashida Ong, the youngest survivor in the iconic photograph that has become a lasting image of the Japanese internment.

Recently Ong returned to Bainbridge Island to visit family, complete some land transfer business, and attend the 80th anniversary of the Japanese Exclusion.

The day prior to the commemoration, Ong visited the memorial to mark the anniversary with her husband Albert Ong and to remember family members who are memorialized on the stone and cedar wall that runs like a waving ribbon toward the ferry dock.

“We’ve been here many times to see the names of people we know, love and miss. It’s quiet and it’s just a very nice place to come,” Ong said.

Ong was too young to remember her time in incarceration, but that famous photo still connects her to an important moment in the history of the Japanese American internment. She hopes that visitors to the memorial will think about how the United States government singled out one community — one ethnic minority — banished them from their homes, took their property, and put them away for three and a half years.

“That’s what strikes me. How could they do that? How did that happen? And yet, I find myself not being very vocal about some of the inequities that are happening in our community now,” Ong said reflectively. “I can understand how my parents thought that way and how others like them did. And I am so grateful for those that speak out for their interests.”

Ong continues to tell her family’s story of incarceration and their transition back to Bainbridge Island after being released from the camps.

“We were one of the fortunate families in that we had property and a place to come back to. A lot of people not only lost their livelihood but lost their homes because they couldn’t make the mortgage payments,” she said.

But, the house was in “bad shape.” So, her older uncle, Tsuneichi Hayashida, returned to the family farm and cleaned up the home before the rest of the family made the trip back to the island.

Reestablishing the strawberry farm was difficult after more than three years of absence, Ong said. “It takes two, maybe three years to get anything going.”

Those first few years, they didn’t make any money from the fruit, so her dad, Saburo Hayashida, went to work for Boeing. He endured long commuting days to and from the island. He would catch a bus on High School Road to the ferry terminal, take the ferry to Seattle and then ride a bus to his job at Boeing — and back again every day.

A few years later, when she was 10 years old, Ong’s parents bought a house in Seattle and settled in Beacon Hill with her two brothers, Neal and Leonard. But, Ong would return to Bainbridge and spend summers helping her aunt and uncle at the strawberry farm.

After graduating from Franklin High School in 1959, Ong went to the University of Washington where she earned a bachelor’s degree in business and met her husband Albert, who worked for Boeing. They married in 1967 and moved to Houston for Al’s job at NASA. Soon after, they moved to El Lago, Texas, a little town near the Johnson Space Center.

There, they grew their family and adopted a son, Gary, from Korea and a daughter, Paula, from Hong Kong and enjoyed living in the unique community with many astronaut neighbors.

“Looking back on it, it was historic,” said Ong. “I used to wave to Neil Armstrong as he drove down the street.”

Ong was very involved in the community. She helped with her children’s school activities, worked as a reporter for the community newspaper and she served as an El Lago City Council member for 12 years.

“Life’s been really good,” Ong said as she plans for the next chapter in her family’s history.

Recently, she finalized details for the sale of the family farm. ”We’ve sold the last of the Hayashida farm that was in my father’s family to the Parks District,” which plans on using it for mountain biking trails.

Happy about the decision to preserve the family property for future generations to enjoy, Ong feels like she’s lost her last tie to Bainbridge Island.

But, the farm will be preserved as a park.

“A benefactor bought the 10.6 acres of the Island Center property from my family and gifted it to the Bainbridge Island Parks District to expand the Strawberry Hill Park off High School Road.

“I was sorry to see the last of my immediate family’s strawberry farm off High School Road sold, but happy that as a park, I and future generations of my family will be able to visit and enjoy the property that was once owned, cleared and planted with strawberries by my Hayashida grandfather, father and uncles.”