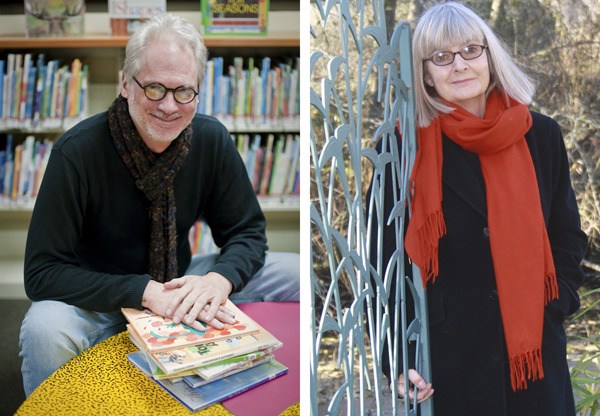

Children’s book author George Shannon noticed Cynthia Sears loitering in the hallway of The Island School where he works Mondays and Tuesdays as the school’s librarian.

“We can’t have adults wandering here unless they’re accompanied by a child,” he teased “the woman who knows everyone.”

To his surprise, she was there to see him.

“Hold out your hand,” she said, pulling out a small velvet bag.

The pin she placed in his hand landed face down, but on the back he could read the inscription: “Island Treasure.”

“For once I didn’t have anything to say,” said the gregarious Shannon followed by his trademark high-spirited laugh. “They must have run out of other people.”

Hardly. Bainbridge is chock-full of creative, talented people working in all mediums. He and fellow 2011 recipient Michele Van Slyke join the luminous company of Joel Sackett, Barbara Helen Berger, David Korten, David Guterson, Ann Lovejoy and Jerry Elfendahl.

The Island Treasure award was conceived in 1999 to honor excellence in the arts and or humanities and is presented annually to two individuals nominated and selected by a double-blind jury process. (See sidebar below.)

A little less contentious than 12 Angry Men.

Champagne?

When Sears paid a visit to artist Michele Van Slyke’s studio, Van Slyke assumed it was to discuss the metal sculpture railing she designed for Yonder, the creative haven on the north end Sears co-owns with husband and Island Treasure, Frank Buxton. But that didn’t explain the champagne bottle Sears brought and presented to the puzzled Van Slyke.

“There’s more,” Sears said, pulling out a crown, the signature headpiece bestowed upon female recipients of the honor.

“I didn’t expect it at all. We’ve been here 40 years,” Van Slyke said, referring to her husband Kent with whom she shares the south end studio/home. By coincidence, or the island’s two degrees of separation factor, Kent designed the Island Treasure trophy that his wife will receive Feb. 25 at the gala awards banquet.

“The first 15 years we were very involved,” she said. “We were young and energetic. We had kids in the schools.”

She was instrumental in establishing the Bainbridge Island Arts Council, which administers the award. She volunteered as artist in residence at the schools, helped BAC move to its present location.

But that was all “before the fire,” Van Slyke says of the 1985 event that serves as a sooty demarcation of their island life.

Much of that activity was “pre-fire,” back when the island was home to a mere 5,000 people.

“Back when you knew everybody by face,” she said. “You could arrive one second before the ferry took off.”

Now that the island’s growth spurt has multiplied that number – and higher taxes have squeezed out the 70s-era artists – she’s surprised people remember her contributions.

The small-town life appealed to Van Slyke who was born and raised in the tiny village of Renaison, France.

After the fire

Because she works out of her studio, which is adjacent to the home she and Kent rebuilt “after the fire,” changes on the island haven’t affected her day-to-day life that much.

“It’s a job,” she said of making a living at making art. “You get up and work. We do what we’re good at. If I was good at computers, I’d do that.”

She thinks art is an important contribution.

“It gets the mind going,” she said. “When you have malls where everything is the same from Anchorage to here to Florida, nothing stimulates the mind much. Whether art is good or bad, it gets you to stop, gets you to think.”

“After the fire,” the petite Van Slyke, who loves color, could “only think in black and white.”

“It wasn’t the death of a family member, but it was the death of a way of life,” she said.

Out of the ashes rose a new focus for her work – functional pieces for the home they were rebuilding. Out of that work came commissions for gates, fences, railings, ornamental screens and more.

Van Slyke doesn’t have a website, just “word of mouth” reputation from projects in France, China, Japan and the West Coast. Her work can be seen around town, at City Hall, the Bainbridge Library, even in the foyer at IslandWood where the Island Treasure awards ceremony will be held.

All in her mind

For Van Slyke, the work begins in the gray matter where she pieces ideas, redrawing them over and over in her mind. It’s not until she sees the work completely that she commits it to paper.

“Clients will ask me what ideas do you have so far, and I tell them I’m thinking about it,” she said. They think I’m not working, but I am. I’m working on it all the time.”

The physicality of the work, drawing large-scale pieces on the floor of her studio, soldering metal, installing work – has taken its toll on her body. Her knuckles are swollen with arthritis and she thinks of slowing down. The idea of making oversized prints has been surfacing for her and she’d like to spend more time with her grandchildren.

“I know I can’t stop and just read books,” she said. “I’ll need to do something.”

Her newest project veers her into the territory of her fellow Island Treasure recipient. She’s written a children’s book, “Skootch the Island Cat.”

She’ll read that to her grandchildren, along with several she’s been reading to them that, she hadn’t realized until recently, were written by Shannon.

In some ways, it’s still a small island after all.

Big Kid

George Shannon has seen a lot of changes in the 40 years he’s been writing stories for children professionally – the rise of the Internet, video games, DVDs in SUVs.

“Kids still love to hear a story told live with the human voice,” Shannon said last week. And they’ve got a few of Shannon’s to choose from. He’s had 40 books published with four more in the works.

As a painfully shy kid growing up in “the metropolis of 1400 people in Caldwell, Kansas, Shannon spent most of his time rummaging through his imagination, concocting stories and pretending. But in seventh grade, he realized the power of print and the positive effect his written stories had on his teacher and classmates.

“I was a dork,” Shannon admits. Storytelling was finally a way to make a connection.

Living in conservative Kansas, the son of the school’s principal, Shannon kept his dream of writing children’s stories to himself. At 16, he sent his first manuscript, “The Blue Stone,” to a publishing house – which promptly rejected it.

He kept at the craft, while attending college majoring in library science and political science during the turbulent late 60s when “librarians were very radical.”

A conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, Shannon wore a “big brown honkey ‘fro” and wore the black armband of the war resistor.

“But I didn’t put it on until after I left the house,” he jokes. “I was political, not a fool”

His big break came when the librarian in a neighboring town ran off to Las Vegas. The void provided Shannon with a foot in the door where he “learned by fire” all the while writing in his free time.

Some writing was “terrible” articles aimed for The New Yorker and the Atlantic Monthly, but most were charming children’s stories. “Lizard Song” caught the eye of an editor at Greenwillow Books and it was published in 1978.

A real job

“I haven’t had a real job since 1978,” Shannon declared, although he’s worked stints at Eagle Harbor Book Company and now, The Island School. What he means is he’s never had to wear a tie.

“Kids are my peers,” he said with his irrepressible exuberance. And he’s shared his stories with plenty of them – all over the U.S., Kuwait, Japan, Indonesia, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Thailand and Alaska. His love of different cultures and perspectives predates his travels. He was immersed in ethnic folktales decades before getting a passport.

When not traveling or touring on behalf of his books, Shannon is on the boards of the library and Field’s End. These days his growing edge is toward theater arts, taking acting and improv classes here and in Seattle.

Though he’s comfortable in the spotlight reading to kids or playing a character, receiving the Island Treasure award makes Shannon a little uncomfortable.

“It’s a big ‘Look at me!’” he said. “I’m flattered and anxious partly from growing up in the Midwest. If you toot your own horn, you go to hell.”

Luckily for Shannon, plenty of others are more than willing to make some noise on his behalf.

Gala award event

The 13th annual Island Treasure Awards Reception and social hour begins at 5 p.m. Feb. 25 at IslandWood.

Tickets are available in January by calling the Arts and Humanities Council office at 842-7901.

Island Treasure Award

“Michele and George embody the spirit of the Island Treasure Award,” Bainbridge Island Art and Humanities Council Executive Director Barbara Sacerdote said. “Their talents and achievements in the visual and literary arts have made an indelible impact on the culture of Bainbridge Island, and the vibrancy of their work is matched only by a consistent generosity in sharing it, and themselves, with the community.”

The Island Treasure selection process is modeled after the MacArthur Genius Awards Program. Each year 10 community members representing a broad range of island arts and humanities organizations are each asked to anonymously nominate one or two outstanding candidates. Candidates’ names and the descriptions of accomplishments are then submitted to a five-member jury comprised of individuals drawn from every aspect of the Bainbridge Island community. The names of the two award recipients are then approved by the Arts & Humanities Council Board. Complete anonymity of nominators, jurists and recipients is maintained throughout the process.

Each Island Treasure receives an unrestricted $4,000 cash award and an Island Treasure Candle Holder Trophy designed by island artist Kent Van Slyke.

For more information, including a list of previous recipients, visit www.artshum.org.