The traffic will ruin downtown.

That’s been one of the biggest concerns generated by the proposed Winslow Hotel project, and one of the main factors in the Bainbridge Island Planning Commission’s recent recommendation that the plans for the hotel be rejected.

But a consultant study conducted for the project shows that island drivers will be delayed a few seconds — at most — once the hotel is built and brings more cars to Bainbridge streets and intersections.

The Winslow Hotel project is currently under additional review by Bainbridge’s Interim Planning Director Heather Wright, who is expected to make a recommendation on the project to the city’s hearing examiner, who will make the final decision on the hotel.

While opponents of the hotel have pointed to a myriad of problems they see as arising from the project — including noise, damage to Winslow’s “small-town charm,” and impacts to neighbors — potential traffic troubles have dominated the debate.

Opponents have said the hotel will generate “significant traffic congestion” and the planning commission, in its decision on the hotel plans, repeatedly referenced the 727 vehicle trips per day that will be generated by the development.

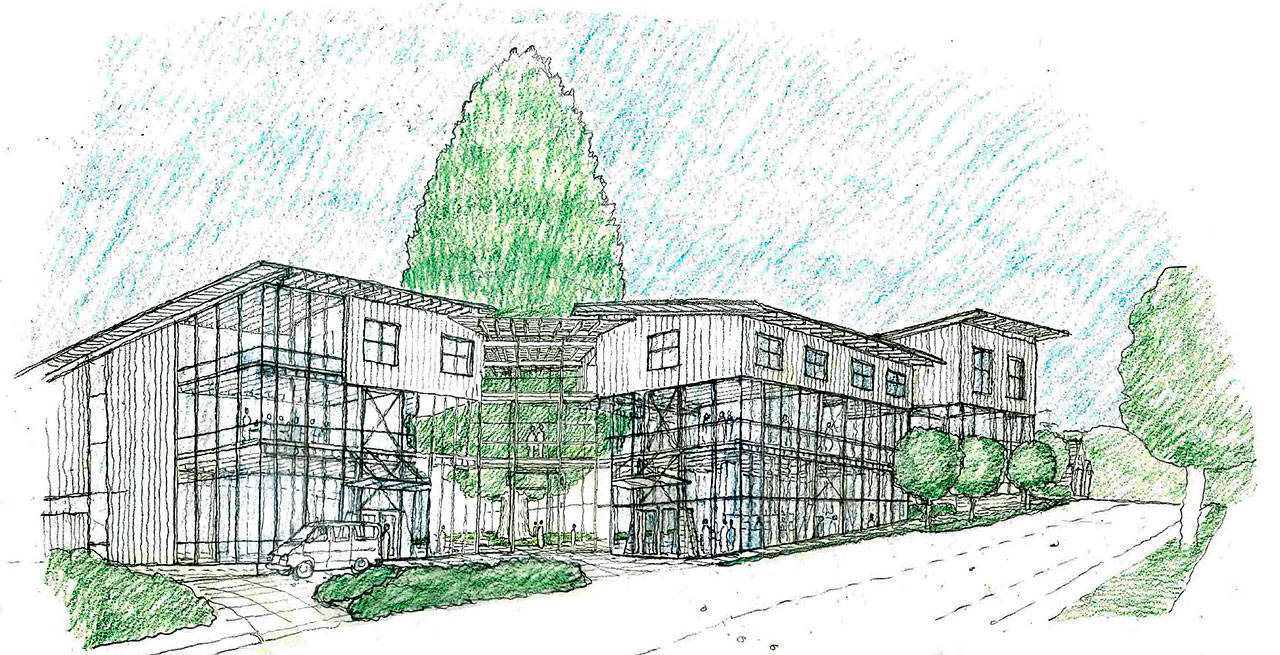

On the other side, however, proponents of the project have repeatedly noted that traffic coming and going from the hotel will be less than what the neighborhood has seen when the hotel site was home to the 122 Bar and a barbecue restaurant, as well as the still-existing office building. Architects with Cutler Anderson Architects, the designers of the hotel, have said the hotel, which includes a restaurant and spa, will add 75 trips during the “peak hour” of road travel — which is less than the 108 “peak hour” trips that were generated by past development of the site.

In the staff analysis of the hotel plans, city officials have said traffic impacts are not big enough to require the developers to provide any street improvements to nearby streets or intersections.

In June, development engineer Peter Corelis recommended approval of the site plan for the 87-room hotel, and said the proposal fit with city regulations on streets, sidewalks, drainage and stormwater, water quality, public water and sewer services.

Corelis also signed off on a “certificate of concurrency” for the hotel project, which determined that the city’s transportation system was good enough as-is to handle the proposed development.

How did they get there? How did the city’s planning and engineering staff, as well as the architects for the project, determine that traffic impacts from the new hotel would be limited?

Both cite an extensive traffic study that was prepared by Heath & Associates, a Puyallup-based transportation and civil engineering firm.

In a 95-page report, issued in April, the traffic consultants studied the current conditions of traffic on Bainbridge, as well as how traffic would change by the year 2021, after the project would be built.

Heath & Associates also studied what traffic would look like during “peak hour” travel times well into the future, in the year 2039. (“Peak hour” is the one hour of the day that has the highest overall volume of traffic.)

The study estimates that the Winslow Hotel will result in average daily traffic of 727 trips, which was the number cited by the planning commission in its recommendation to deny the project.

How much hourly traffic does that break down to?

According to the traffic study, the hotel will generate 41 total “peak hour” trips in the morning (mostly from people arriving), while there will be 52 “peak hour” trips during the p.m. (evenly split between arrivals and departures).

The peak hour numbers, and by extension, the average number of daily trips, that may result from the hotel are actually lower than what was forecast in the traffic study.

Heath & Associates said their estimates of new trips are a “conservative forecast,” because many trips by hotel users will be in the form of shuttle trips — the hotel developers have promised to set up a shuttle from the hotel to the Winslow ferry terminal — or that hotel guests won’t get in their cars but instead walk to nearby attractions and amenities.

The estimates are conservative, as well, because the study did not deduct existing travel trips that are due to the existing on-site retail development and restaurant on the hotel site.

When that existing traffic is removed, the consultants said, the number of new p.m. peak hour trips drops from 52 to 25.

The destination hotel is planned for a two-parcel, 1.85-acre property at the western end of the city’s main street, Winslow Way. The land is located in Bainbridge’s Central Core, which city planners say is “the most densely developed district” on the island.

The traffic study relied on traffic counts done on the island in October 2018.

Seven intersections were studied: Grove Avenue/Winslow Way; Winslow Way/Madison Avenue; Winslow Way/Highway 305; Madison Avenue/Wyatt Way; Madison Avenue/High School Road; Madison Avenue/Highway 305; and Highway 305/High School Road.

Currently, the heaviest traffic during the morning peak hour travel time is on southbound Highway 305 at Madison Avenue (867 vehicles counted), followed by northbound Highway 305 traffic at High School Road (566 vehicles counted).

At the busiest intersection near the Hotel Winslow site — at Winslow Way/Madison Avenue — the heaviest traffic in the morning is actually southbound drivers on Madison Avenue (225 vehicles counted), followed by eastward traffic on Winslow Way through the intersection (164 vehicles counted).

For existing traffic in the p.m. peak hour, the busiest intersection is northbound Highway 305 at Madison Avenue (605 vehicles counted) followed by eastbound traffic on High School Road at Highway 305 (580 vehicles counted).

The study also forecast how much additional traffic created by the hotel project will add to delays for travelers through six intersections.

Weekday peak hour a.m. traffic is expected to increase by .3 seconds for people driving through the roundabout at High School Road and Madison Avenue. (Without the hotel project, drivers will face an expected delay of 15.3 seconds at the roundabout in 2021.)

Morning peak hour traffic delays at the Madison Avenue/Winslow Way intersection is expected to be .5 seconds longer by 2021 (rising to 11.6 seconds), after the hotel is built, while no increase in time is expected for drivers going through the Grove Avenue/Winslow Way intersection, which is forecast to slow drivers down by 8.3 seconds. (The p.m. peak hour delay is expected to increase by .4 seconds at Madison Avenue/Winslow Way, from 12.3 to 12.7 seconds, and remain unchanged at Grove Avenue/Winslow Way.)

An additional delay of .2 seconds is forecast at the Madison Avenue/Wyatt Way intersection for the a.m. peak hour, while traffic delays at the Highway 305/Madison Avenue intersection are also expected to grow by .2 seconds. (The p.m. peak hour delay is expected to increase 1.2 seconds at Madison Avenue/Wyatt Way to 24.6 seconds, and grow by .3 seconds at Highway 305/Madison Avenue) to 17.7 seconds.

Overall, the hotel project is expected to add little to overall traffic at the intersections studied over the next 20 years.

The biggest increase is expected at the Madison Avenue/Winslow Way intersection, where total traffic volume is expected to grow by 4.4 percent during the p.m. peak hour in 2039. The overall traffic volume at Highway 305/Winslow Way is forecast to grow by 1.9 percent due to new trips to the hotel by the year 2039.

While the Heath & Associates analysis was accepted by the city as an adequate prediction of possible traffic impacts from the Winslow Hotel proposal, the study has raised questions from those who are opposing the hotel project.

Planning commissioners, in their decision on the hotel plans, said the traffic analysis was not adequate because it didn’t consider traffic surges from ferry loading and unloading, and noted it didn’t determine if traffic impacts would be “materially detrimental” on other properties in the area.

A memo submitted to city planners by Ross Tilghman, a transportation planning consultant, found fault with the analysis of potential traffic impacts because it did not take into account events at the hotel, which Tilghman said could attract up to 200 people.

Tilghman also noted the traffic counts were conducted in the winter, which has lower volumes of traffic than summertime. Data from Washington State Ferries, he said, shows ferry volumes are 27 percent higher on average during the summer.

He also said the study had not considered “surges from ferry traffic,” which he called a “crucial oversight” due to possible impacts from hotel event traffic on Winslow Way.