You may not be ready for next year’s elections, but in political time, they’re coming up fast. Even politicians who aren’t running for president are crafting their stump speeches. Which means that at some point you’re almost certain to hear someone announce, sternly, “I. Will. Not. Compromise.” And if you’re there in the crowd and agree with his or her position, you may even join the applause.

Which is understandable, but let me tell you why, far from applauding that line, I shy from politicians who use it. In a democracy, being able to compromise — and knowing how — is a core skill for governing. Shouting “No Compromise!” may fire up the crowd, but it’s a recipe for failure when it comes to getting things done in office.

In fact, it was a core skill even before we had our current system. Pretty much every sentence in our Constitution was the product of compromise, crafted by people who felt passionately about the issues they confronted yet found a way to agree on language that would enable the country to function.

It is true that any legislative body needs members who set out the vision — the pure ideological positions — as part of the public dialogue. But if they’re allowed to control or dominate the process, nothing gets done. When pushed, most politicians understand that cooperation and working together to build consensus have to prevail in the end.

So why doesn’t it happen more? Because compromise is not easy, especially on issues of consequence, and especially today, when the country is so deeply divided and polarized. Even the word itself causes disagreement. To someone like me, it’s a way forward. To others, including a lot of voters, it’s a betrayal of principle.

Once you do compromise, you’ve always got the problem of selling the result to others. Sometimes, in fact, you have the problem of selling it to yourself. When I was in office, I often found myself second-guessing my own decisions. Did I give up too much on principle? Was there another path to the same goal without compromising? Maybe I didn’t give enough? Is the compromise that emerged actually workable?

This last is an important question. Any politician seeking to forge common ground with others has to weigh whether people — voters and colleagues outside the meeting room — will be willing to accept or at least tolerate a compromise. I’ve certainly encountered politicians who have walked out of efforts to reach agreement because they felt they couldn’t sell it. Or, even more common, who support compromise as long as it’s the other side that does all the compromising.

The thing is, politicians never control the political environment in which they’re working. They have to seek the best solution given the cards they’ve been dealt. They can’t dictate who’s on the other side of the negotiating table, or the political climate in their community.

This makes the kind of people you’re dealing with supremely important. As a lawmaker or officeholder seeking to move forward and faced with colleagues who may hold very different views, you need counterparts who know they need to make the system work and are willing to be flexible. In a way, you’re hoping for politicians who take into consideration the broad concerns of the entire population, not just those who support them or voted for them.

In Central Park one day during WWII, Judge Learned Hand told an assembled crowd, “The spirit of liberty is the spirit which is not too sure that it is right; the spirit of liberty is the spirit which seeks to understand the mind of other men and women; the spirit of liberty is the spirit which weighs their interests alongside its own without bias.” That is also the spirit of our representative democracy, and we need politicians who embrace it.

So when Americans complain about Congress not getting anything done, I have limited sympathy. Congress struggles because it has members who don’t know how to compromise, are afraid to, or don’t want to. And those members are there because we sent them there. In other words, we share the blame.

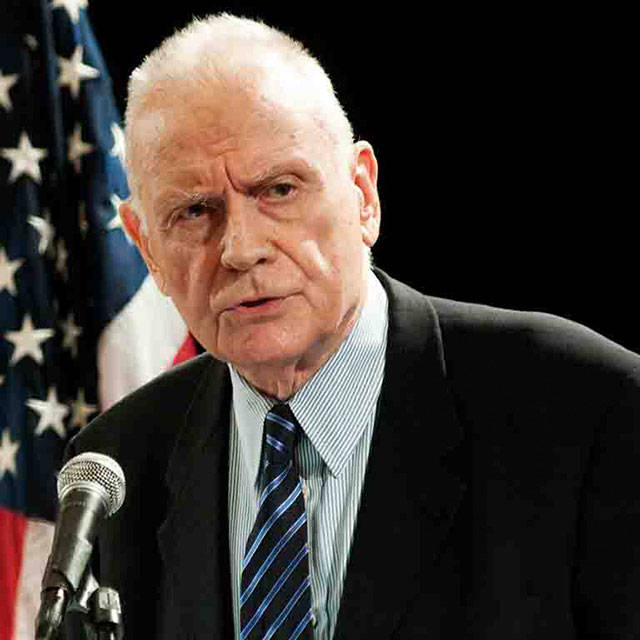

Lee Hamilton is a Senior Advisor for the Indiana University Center on Representative Government; a Distinguished Scholar at the IU Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies; and a Professor of Practice at the IU O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs. He was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for 34 years.