Back in 1883, Teddy Roosevelt wrote an essay on what it takes to be a true American citizen. He did not mince words. “The people who say that they have not time to attend to politics are simply saying that they are unfit to live in a free community,” he wrote. “Their place is under a despotism.”

He went on: “The first duty of an American citizen, then, is that he shall work in politics.”

I hope you’ll forgive his gender-specific language. He wrote at a time when women didn’t even have the vote. But his essay has been on my mind lately, because his sentiment — that living in a representative democracy demands work from all of us — is as timely now as it was then. A lot of people these days intuitively grasp that our system needs our involvement if we’re to safeguard it. So what should we do — especially if politics has to share space in our lives with family and jobs?

The first step is easy: Look around your community and ask yourself what needs fixing or what can be done better. I don’t care where you live: 10 minutes’ thought and you’ll come up with a healthy list of issues to tackle. This is how a lot of people get started: They see an issue they want to do something about. So they enter the fray, and often come to recognize they have more political power than they thought.

Of course, your chances of effecting change grow as you learn. You have to inform yourself about the issue: Listen carefully as you talk to your neighbors and friends, and pay attention to what politicians, commentators, and those involved with the issue say. Participate, if you will, in the dialogue of democracy. It’s perfectly fine to personalize the issue as you seek to persuade others, but to be effective you’ve got to know what others think, too.

The same, really, goes for voting. It should be informed not just by what your gut tells you, but by what you’ve learned. Our system depends on citizens making discriminating choices on politicians and issues. So you want to educate yourself, which includes talking with people whose opinions differ from yours. The world is complex, even at the neighborhood level, and to be effective we need to understand it.

When it comes time to act, you want to join with a like-minded group of believers. That’s how you amplify your strength. Numbers count. And both within that group and among the others you’ll encounter, you try to build consensus. There’s an old saying that if you want to go fast you go alone, if you want to go far you join together. That’s very true in politics.

Next, you have to communicate — with each other, with the media, and at the local, state, and national levels. You have to communicate with your representatives. You have to go to public meetings and speak up. Focus your message so it’s clear, concise, and specific. Be polite but persistent.

There’s another way of participating that’s a bit more arms’ length, but also important: contribute money to a party or politician of your choice. Doing it is as important as the amount, because money talks in politics, and it helps you expand your influence. For good or ill, it’s an important part of politics.

Finally, run for office yourself. If you are so inclined, get a circle of friends to support you. Start locally. Develop the issues you’re interested in, pick the office that will help you affect them, organize and build support, focus your message, raise money. If this isn’t to your taste, then support candidates of your choice.

All of these are ways of participating — and if you want more, search out The New York Times’ guide, “How to Participate in Politics.” The key thing, as President Obama said, is to show up. There are all kinds of ways to have an impact, but they start with one thing: Showing up. It’s the least we should do.

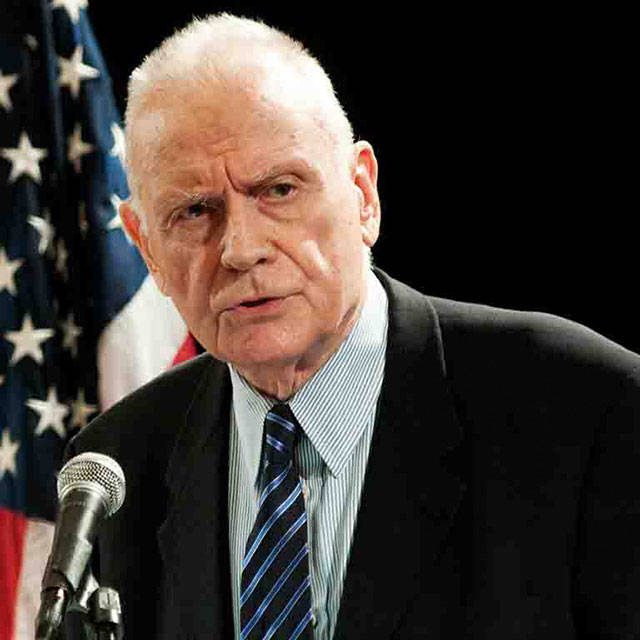

Lee Hamilton is a Senior Advisor for the Indiana University Center on Representative Government; a Distinguished Scholar, IU School of Global and International Studies; and a Professor of Practice, IU School of Public and Environmental Affairs. He was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for 34 years.