There’s a community to which Bainbridge Island will forever be tied by history, a community with a message for every American. It’s as much a part of our island soul as Manitou Beach, Yeomalt, Restoration Point, Island Center, Blakely or Eagle Harbors, all of Port Madison, Strawberry Hill or Hermana Isla de Ometepe. I heard about Minidoka, Idaho sparingly as a student, more over the years. In 2007, I could not stay away.

Islanders took the train there 66 years ago via a year’s detour in the California desert. Seattle neighbors traveled a more idyllic-sounding route from “Camp Harmony” to the Idaho towns of “Bliss” and “Eden.” With names like that, who wouldn’t want to go? Though their route was scenic, they were required to keep the window shades down. It was World War II. They looked like the enemy from Japan.

Today, one interstate umbilical to this community winds 650 miles from cool coastal forests, southeasterly across the mighty Columbia and through sparse pine-covered hills bearing Oregon Trail wagon ruts past Boise to Twin Falls. It’s the heart of what locals call “Magic Valley” in the windy state of “Idablow.”

Except for a deep, narrow canyon carved by the Snake River, it’s a plain – flat and mountainless. You can see forever in all directions. Puget Sound navigators fidget, “Where am I?” If not for vast irrigation, tumbleweed might fly to nearby Utah or Nevada. Instead, it is a vast checkerboard of fertile green farms.

After Pearl Harbor, the FBI rounded up coastal leaders of Japanese ancestry. Gone were teachers, ministers, business owners, professional people and those who’d recently attended college in Japan. Gone. They weren’t spies. They were not guilty of crimes. No matter. They were neighbors at the wrong place at the wrong time. Some were simply birdwatchers or photographers with binoculars or cameras within view of shipping lanes. They were merely “suspicious” enough to be put behind bars.

Spouses and children were frequently left behind to fend for themselves. Some could not. On presidential orders, all coastal American Japanese were uprooted – forced to evacuate coastal areas. A few families from Bainbridge retreated east of the mountains who had homes there. Some were already there farming. But most of them (120,000) were hauled to instant-cities quickly being erected inland.

Initially, most Bainbridge Islanders were taken to Manzanar, a California relocation camp housing urban zoot-suiters, politically active Issei and Nisei from Los Angeles. They protested the unjust incarceration and riots ensued. Some died from stress and rifle fire from guards. Some cried, “It’s no place to raise kids! Ship us back north!” A few stayed. Others were sent by train to Minidoka, a Lakota Sioux word for water.

Idaho’s “seventh largest city” was considered a concentration camp by those living there. They had lost their freedom, yet a third worked outside the camp on farms. The newcomers’ plight seemed strange to Japanese farmers who’d lived in the valley before the war. When kids smoking caused a guard tower to catch fire, no one bothered to replace it.

They were not, as is frequently assumed, just thrown out in the desert to rot. Historians assert that they were placed there by a government needing workers to farm the vacant, recently irrigated Bureau of Reclamation farmland. There, despite being unjustly incarcerated based on race – not loyalty or citizenship – they grew vegetables to feed their nation at war. Many had lost their homes, businesses and life savings. Seventy-three of them also lost sons who died while serving overseas as members of the U.S. Army.

Today, the rich volcanic soil is lush. Irrigation sprinklers run round the clock. Vast acres produce beef and vegetables. Wind farms generate electricity. Aquaculturists raise trout – even alligators! – though their aquifer is being depleted by about a foot a year. Tourists play golf, visit fossil beds and Minidoka National Internment Memorial. Many wonder, “Did this really happen?”

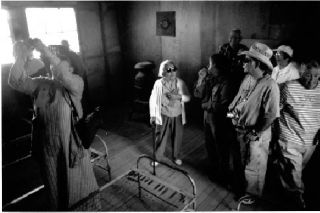

The proposed Bainbridge Island World War II Nikkei Interment and Exclusion Memorial is considered a “satellite” of Minidoka National Landmark and is expected soon to also become part of the National Park Service, as are Manzanar and Minidoka. Planning for each memorial has been extensive. For the past six years, Friends of Minidoka (including BIJAC president Dr. Frank Kitamoto, Idaho farmers, Minidoka internees, National Park Service staff, historians, architects and educators) have held a remarkable three-day, “Minidoka Pilgrimage” – welcome to all.

This year’s event, scheduled for June 20-22, will be preceded by a two-day symposium on “Civil Rights in Wartime” at the College of South Idaho in Twin Falls.

For details, see www.minidokapilgrimage.org.

Gerald Elfendahl is a local historian.