Looking back at 2018’s weather-related news, it seems clear that this was the year climate change became unavoidable.

I don’t mean that the fires in California, coastal flooding in the Carolinas, and drought throughout the West were new evidence of climate change. Rather, they shifted the national mindset. They made climate change a political issue that cannot be avoided.

The Earth’s climate changes all the time. But what we’re seeing today is different: the increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather. Wet places are becoming wetter; dry places are growing dryer; where it was hot a generation ago, it’s hotter now; where it’s historically been cool, it’s growing warmer.

The global impact of human activity — specifically, the burning of hydrocarbons — is shuffling the deck. And we’re only beginning to grasp the impact on our political and economic systems.

Warmer overall temperatures, for instance, have lengthened the growing season across the U.S. — by about two weeks compared to a century ago. But the impact on fruit and grain production isn’t just about the growing season: plant diseases are more prevalent, and the insects that are vital to healthy agricultural systems are struggling. Insects that spread human diseases, like mosquitoes and ticks, are flourishing.

Precipitation is also changing. There will be more droughts and more heat waves, which will become especially severe in the South and West and in cities.

This is troubling news. Extreme heat, according to the Centers for Disease Control, “often results in the highest number of annual deaths among all weather-related hazards.” In other words, it kills more people than other weather-related disasters. The human cost and strain on public resources of prolonged heat waves will be extensive.

The rise in sea levels will be even more disruptive. Sea levels have been increasing since we began burning fossil fuels in the 1880s, but the rise is occurring at a faster rate now, something like six to eight inches over the past century — compared to almost nothing during the previous two millennia. This already poses a threat to densely populated coastal areas — in the U.S., about 40 percent of the population, or some 120 million people, lives directly on the shoreline.

And that’s without the very real potential of melting glacial and polar ice, with calamitous results. It’s not just that this would affect coastal cities, it would also scramble the geopolitical order as nations like the U.S., Canada, and Russia vie for control over the sea lanes and newly exposed natural resources.

I’m not mentioning all this to be alarmist. My point is that dealing with climate change constitutes a huge, looming challenge to government. And because Americans are fairly divided in their beliefs about climate change — a division reflected in sharp partisan disagreements — policy makers struggle to come up with politically viable approaches. This makes the adverse impacts of climate change potentially much worse, since doing nothing is clearly a recipe for greater disaster.

The problem is that politicians in Washington like to talk about climate change in general, yet we haven’t seen any concerted consensus-building effort to deal with it. Occasionally you’ll see bills being considered in Congress to study it more, but unless we get real, this will dramatically change our way of life.

And despite the growing impact of extreme weather, the opposition’s point — that policies to fight climate change will impose hardship on working people, especially in manufacturing states — still has some merit and political legs. In response to inaction in Congress and the administration, some states have taken important steps to address climate change, even though it’s best dealt with on the federal level.

Still, newer members of Congress appear to have more of an interest in addressing climate change than older, senior members. And the issue holds particular resonance for younger millennial voters, whose political influence will only grow over coming elections.

Only recently have thoughtful politicians I talk to begun to ask whether the political system can deal with the challenges posed by climate change before its impact becomes unstoppable. The one thing we agree on is that climate change and how to deal with it will place real stress on the system in the years ahead.

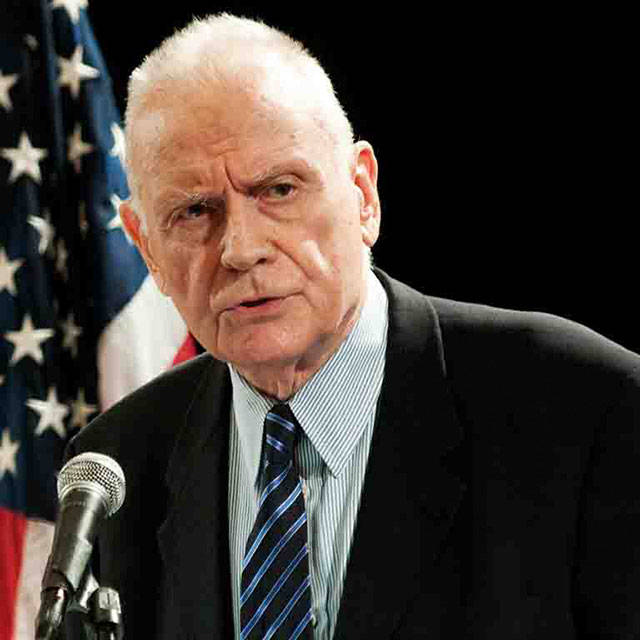

Lee Hamilton is a Senior Advisor for the Indiana University Center on Representative Government; a Distinguished Scholar of the IU Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies; and a Professor of Practice, IU School of Public and Environmental Affairs. He was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for 34 years.