Each of the great politicians and legislators I’ve known over the course of my career in Congress was very different.

They were masters of the rules, or unassailably knowledgeable about a given issue, or supremely watchable orators, or consummate students of people. But they also shared key traits that I wish more elected officials possessed.

For starters, the great politicians I’ve met enjoyed the game, and they worked on the skills needed to play it well. They were adept both as politicians and as legislators — which is not as common as you might imagine. They were good speakers and adroit persuaders, whether on the floor of the Congress, addressing a convention of thousands, or sitting in a supporter’s living room with a dozen strangers.

The men and women I most admired embraced a life in politics because they believed they could make a difference. They had confidence in themselves, their ideas, and their ability to find their way out of tough spots. They were not dismayed by the give and take of politics — if anything, they relished it. They might have faced heavy criticism for a political stance or legislative maneuver, but they were never defeated by that.

And they could master legislative detail. This may be hard to see from afar, but serious legislating requires mind-numbing work — sitting alertly through hours of expert testimony; digesting the reports of committees and subcommittees; thinking through how even small word changes can affect the course of legislation or the impact of a law; going through the intense editing process known as legislative “markup.”

Effective legislators not only don’t mind this, they see it as an opportunity to put their imprint on the law.

As I think back on men like Tip O’Neill or John Anderson or Mike Mansfield, and on women like Edith Green and Lindy Boggs, I’m struck by their sense of obligation to the country and their palpable commitment to doing the right thing.

They worked long, almost inhuman hours, and sometimes they made mistakes, but they were never bowled over by them — they believed they were helping to push the country forward, and that was a powerful motivator to stay in the fight.

Many of the strongest political leaders I met over the years had a passion for leadership. This may seem obvious, but think about it: there are 435 members of the House and 100 senators, and simply by virtue of being there they’ve exercised leadership in one form or another. So the people who in turn rose to the top of those ranks had something extra: they wanted to be leaders of the leaders.

And not just in Congress. Their attitude toward the presidents they served with was interesting. They obviously had areas of agreement and disagreement on policy, but underlying those were two key themes: They had a deep respect for the office of the presidency, and they insisted that the president display equal respect for the Congress.

If a president in some way showed disregard or disdain for Congress as an institution, that was a serious mistake, because people like O’Neill and Mansfield took the idea of a co-equal branch of government seriously.

They applied the same sensibility to their colleagues. They were serious about strengthening the institution from the inside. They recognized that their work could only be completed if the institution was shored up and reformed in a way that gave it the strength to push its goals forward.

They sought to build its capabilities — for research and analysis, for oversight, and for all the capabilities a branch of government charged with making policy might need.

When he first arrived in what he called the “President’s house” — the first president to do so — John Adams wrote to his wife Abigail to let her know he had arrived and that “The Building is in a State to be habitable.” And then he appended this: “May none but honest and wise Men ever rule under this roof.”

Forgiving him his assumption about a president’s gender, isn’t that the hope we all have to possess as citizens? That our political leaders are ever honest and wise? I certainly do.

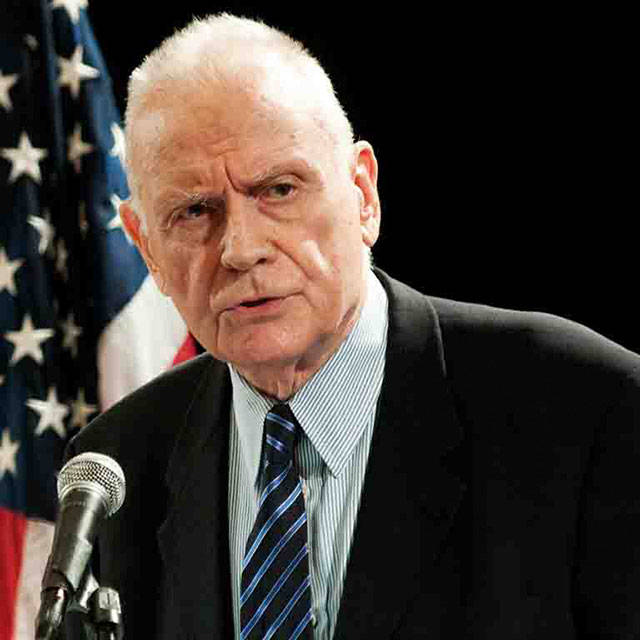

Lee Hamilton is a Senior Advisor for the Indiana University Center on Representative Government; a Distinguished Scholar of the IU Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies; and a Professor of Practice, IU School of Public and Environmental Affairs. He was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for 34 years.