As U.S. college students — and their families — know all too well, the cost of a higher education in the United States has skyrocketed in recent decades.

According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, between 2008 and 2017 the average cost of attending a four-year public college, adjusted for inflation, increased in every state in the nation. In Arizona, tuition soared by 90 percent. Over the past 40 years, the average cost of attending a four-year college increased by over 150 percent for both public and private institutions.

By the 2017-2018 school year, the average annual cost at public colleges stood at $25,290 for in-state students and $40,940 for out-of-state students, while the average annual cost for students at private colleges reached $50,900.

In the past, many public colleges had been tuition-free or charged minimal fees for attendance, thanks in part to the federal Land Grant College Act of 1862. But now that’s “just history.” The University of California, founded in 1868, was tuition-free until the 1980s. Today, that university estimates that an in-state student’s annual cost for tuition, room, board, books, and related items is $35,300; for an out-of-state student, it’s $64,300.

Not surprisingly, far fewer students now attend college. Between the fall of 2010 and the fall of 2018, college and university enrollment in the United States plummeted by 2 million students. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the United States ranks 13th in its percentage of 25- to 34-year-olds who have some kind of college or university credentials, lagging behind South Korea, Russia, Lithuania, and other nations.

Furthermore, among those American students who do manage to attend college, the soaring cost of higher education is channeling them away from their studies and into jobs that will help cover their expenses. As a Georgetown University report has revealed, more than 70 percent of American college students hold jobs while attending school. Indeed, 40 percent of U.S. undergraduates work at least 30 hours a week at these jobs, and 25 percent of employed students work full-time.

Such employment, of course, covers no more than a fraction of the enormous cost of a college education and, therefore, students are forced to take out loans and incur very substantial debt to banks and other lending institutions. In 2017, roughly 70 percent of students reportedly graduated college with significant debt. According to published reports, in 2018 over 44 million Americans collectively held nearly $1.5 trillion in student debt. The average student loan borrower had $37,172 in student loans — a $20,000 increase from 13 years before.

Why are students facing these barriers to a college education? Are the expenses for maintaining a modern college or university that much greater now than in the past?

Certainly not when it comes to faculty. After all, tenured faculty and faculty in positions that can lead to tenure have increasingly been replaced by miserably-paid adjunct and contingent instructors — migrant laborers who now constitute about three-quarters of the instructional faculty at U.S. colleges and universities. Adjunct faculty, paid a few thousand dollars per course, often fall below the official federal poverty line. As a result, about a quarter of them receive public assistance, including food stamps.

By contrast, higher education’s administrative costs are substantially greater than in the past, both because of the vast multiplication of administrators and their soaring incomes. According to the Chronicle of Higher Education, in 2016 (the last year for which figures are available), there were 73 private and public college administrators with annual compensation packages that ran from $1 million to nearly $5 million each.

Even so, the major factor behind the disastrous financial squeeze upon students and their families is the cutback in government funding for higher education. According to a study by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, between 2008 and 2017 states cut their annual funding for public colleges by nearly $9 billion (after adjusting for inflation). Of the 49 states studied, 44 spent less per student in the 2017 school year than in 2008. Given the fact that states — and to a lesser extent localities — covered most of the costs of teaching and instruction at these public colleges, the schools made up the difference with tuition increases, cuts to educational or other services, or both.

For example, SUNY, New York State’s large public university system, remained tuition-free until 1963, but thereafter, students and their parents were forced to shoulder an increasing percentage of the costs. This process accelerated from 2007-08 to 2018-19, when annual state funding plummeted from $1.36 billion to $700 million. As a result, student tuition now covers nearly 75 percent of the operating costs of the state’s four-year public colleges and university centers. This is not atypical.

This government disinvestment in public higher education reflects the usual pressure from the wealthy and their conservative allies to slash taxes for the rich and reduce public services. “We used to tax the rich and invest in public goods like affordable higher education,” one observer remarked. “Today, we cut taxes on the rich and then borrow from them.”

Of course, it’s quite possible to make college affordable once again. The United States is far wealthier now than in the past, with a bumper crop of excessively rich people who could be taxed for this purpose. Beginning with his 2016 presidential campaign, Bernie Sanders has called for the elimination of undergraduate tuition and fees at public colleges, plus student loan reforms, funded by a tax on Wall Street speculation. More recently, Elizabeth Warren has championed a plan to eliminate the cost of tuition and fees at public colleges, as well as to reduce student debt, by establishing a small annual federal wealth tax on households with fortunes of over $50 million.

Certainly, something should be done to restore Americans’ right to an affordable college education.

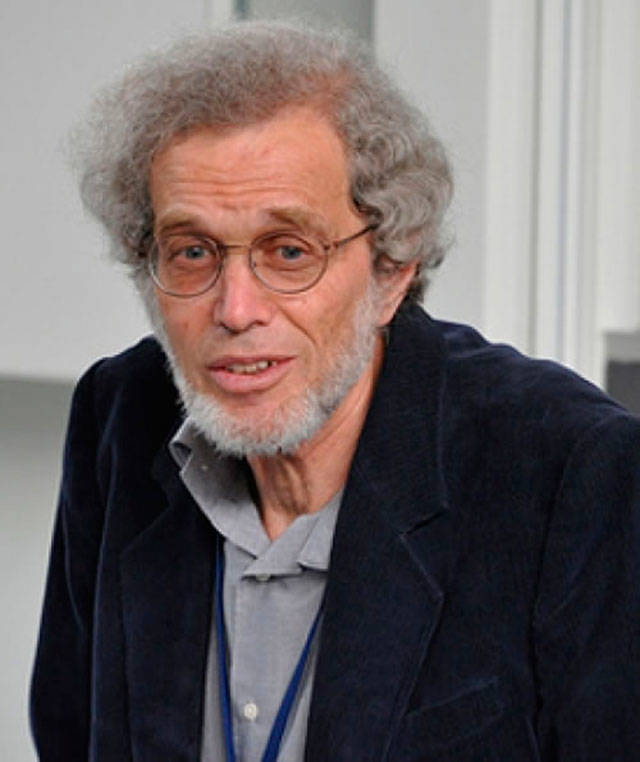

Dr. Lawrence Wittner, syndicated by PeaceVoice, is Professor of History emeritus at SUNY/Albany and the author of “Confronting the Bomb” (Stanford University Press).