America’s oft-quoted Declaration of Independence, when discussing “unalienable rights,” focused on “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Although “happiness” is rarely referred to by today’s government officials, the general assumption in the United States and elsewhere is that governments are supposed to be fostering the happiness of their citizens.

Against this backdrop, it’s worth taking a look at the 2018 World Happiness Report, released in mid-March 2018 by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, a U.N. venture.

Drawing on Gallup Poll surveys of the citizens of 156 countries from 2015 to 2017, the report, written by a group of eminent scholars, focused on the influence of per capita gross domestic product, social support, healthy life expectancy, social freedom, generosity, and absence of corruption in securing public happiness. Its rankings were based on assessments by people in different nations of their well-being.

What the report found was that the nations whose people reported themselves happiest were: Finland, Norway, Denmark, Iceland and Switzerland. And right after these came the Netherlands, Canada, New Zealand, Sweden and Australia.

By contrast, the allegedly “great” powers that have proclaimed themselves models for the world — including the United States, Britain, France, Germany, Russia, and China — fared relatively poorly.

The United States ranked 18th (having dropped four spots from the previous year’s report), while Russia placed 59th and China 86th.

The 10 happiest nations share a number of characteristics. Preeminent among them is the fact that they have been governed for varying periods by Social Democratic and other parties of the moderate Left that have provided the populations of their countries with advanced social welfare institutions. These include national health care, free or inexpensive higher education, child and family support, old-age pensions, public housing, mass transit facilities, and job retraining programs―usually funded by substantial taxes, especially on the wealthy. Certainly the five Nordic countries that appear among the 10 happiest nations, with four of them occupying the top four spots, fit this model very well.

As Meik Wiking, CEO of Copenhagen’s Happiness Research Institute, remarked, they “are good at converting wealth into well-being.” They have also been good at defending the rights of workers, women, immigrants, racial and religious minorities, and other disadvantaged groups.

Of course, it’s also true that the 10 happiest nations are relatively prosperous ones. And the least happy nations tend to be those that are most impoverished.

Nonetheless, wealth alone cannot account for the highest rankings. Finland (No. 1) has less than half the wealth per adultthat the United States (No. 18) has, while Norway, Denmark, Sweden, New Zealand, Canada and the Netherlands also lag behind the United States in average wealth per adult. Discounting the dominant influence of wealth on national happiness, the writers of the report contend that belonging and respect in civil society also play vital roles, as do “high levels of mutual trust, shared purpose, generosity, and good governance.” A minimum level of economic well-being might be necessary to pull people out of misery, but once this level has been reached, further wealth doesn’t necessarily produce greater happiness.

The United States provides a good example of this point. As Professor Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia University observes in the 2017 report, America’s per capita gross domestic product continues rising, “but happiness is now actually falling.”

Indeed, between 2012 and 2018, the U.S. happiness ranking dropped from 11th to 18th.

Over the years, he notes, there has been a “destruction of social capital” in the United States, caused by the power of “mega-dollars in U.S. politics,” “soaring income and wealth inequality,” a “decline in social trust” related to immigration, a climate of fear triggered by the 9/11 attacks, and a “severe deterioration of America’s educational system.” Economic growth, Sachs argues, has not been (and will not be) successful in fostering greater American happiness. That will only be secured “by addressing America’s multi-faceted social problems — rising inequality, corruption, isolation and distrust.”

One factor not considered by the report is the role of violence in reducing happiness. The 10 happiest nations certainly have much lower murder rates than the United States and Russia.

Also, when it comes to gun homicide rates, these vary from 1/35th (Norway) to 1/8th (Canada) of the rate in the United States.

It is also worth noting that at least five of the world’s least happy countries are war zones: Ukraine (No. 138), Afghanistan (No. 145), Syria (No. 150), Yemen (No. 152) and South Sudan (No. 154).

Although the 10 happiest nations maintain armed forces, none can be classified as a major military power or has chosen to become one.

For example, given their economic strength and technological prowess, they could easily develop nuclear weapons. But none has opted to do so.

This contrasts with the nine nuclear powers, which retain some 15,000 nuclear weapons and are engaged in a new, vastly expensive nuclear arms race. Whatever else these nuclear nations have achieved through prioritizing the building of nuclear weapons, it has not — as the happiness rankings show us — led to widespread happiness among their citizens.

Overall, then, it appears that the pursuit of ever-greater wealth and military power by national governments doesn’t necessarily create happiness for their people.

By contrast, governments that seek to improve everyone’s lives — or, in the words of the preamble to the U.S. Constitution, “promote the general welfare” — do a much better job of it.

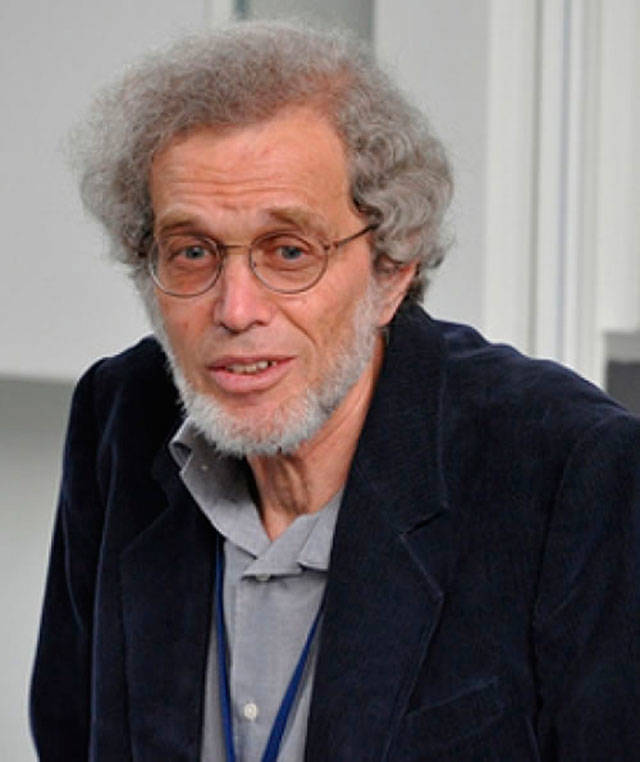

Dr. Lawrence Wittner, syndicated by PeaceVoice, is Professor of History emeritus at SUNY/Albany and the author of “Confronting the Bomb” (Stanford University Press).