“I was hoping that this call would be the one to set me up for the rest of my life,” said island photographer Pete Saloutos last month.

The offer was considerably less: a request to shoot a Spartan JV basketball game for this publication on a Saturday afternoon in the midst of the busy Christmas season, during a year that Saloutos terms “the worst of my 36 years as a professional photographer” because of fallout from Sept. 11.

Though there was virtually no glory in the assignment – most readers probably don’t even notice photo credits – and very little money, Saloutos didn’t hesitate to accept.

For a bit of perspective, think of Minnesota Vikings’ star wide receiver Randy Moss, who recently said he puts out a full effort “only when I feel like it.” Then turn your mental compass exactly 180 degrees in the opposite direction.

Saloutos – consistently featured in Nikon promotional materials as a “Legend Behind the Lens” – is a consummate pro. And a pro with a long history of helping out with community events by staging benefit showings of his work, in particular his sports photography.

“I try to save the whales every way I can,” he says. He’s supported local causes such as Gazzam Lake, the new pool, families of the medical helicopter that crashed several years ago and Sept. 11 victims.

Though Saloutos estimates that only about 25 to 30 percent of his income from his total yearly output of 25,000-50,000 images per year is directly sports-related, it may be the closest to his heart.

Growing up in Venice, Calif., Saloutos describes himself as “as absolutely a beach kid, through and through.”

Living not far from the fabled California oceanfront, Saloutos became an inveterate surfer.

“Basketball was my other sport,” he says. “I’d play every night after school.”

Now he channels that energy into almost daily 4:00 a.m. gym workouts. “And I walk a lot,” he adds.

He’s passed on his passion for sports to his kids: Alexis, 18, a sophomore at Seattle Central Community College, played volleyball and is currently an avid body-builder. Teddy, 15 and a BHS sophomore, plays soccer. Tina, 13, is a Woodward seventh-grader who also plays volleyball. Both the girls were swimmers at one point.

Though he began his professional career when he entered college in 1965 – “By 1966 I was up to my elbows in weddings and sorority pictures,” he recalls – it wasn’t until the early 90s that he was able to add sports to his by-then heavily corporate repertoire with the introduction of the Nikon N90S auto-focus camera.

In the decade since then, there are few sports that Saloutos hasn’t photographed.

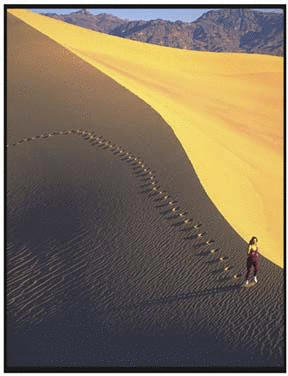

What is remarkable is his ability to avoid hackneyed images, to continually come up with dramatic new twists on activities that are already familiar to us through countless thousands of previous photographs. He is especially adept at incorporating existing light into his images, whether it’s stark, direct desert light or dappled sunlight filtering through trees behind a runner onto a dusty road.

Regardless of the sport, his approach is always the same.

“The particular event is irrelevant,” he explains. “I shoot a concept, using the activity as a metaphor for something else. Typically I won’t shoot something unless I can make it interesting. I’ll pick out the best talent, wardrobe, lighting and facilities. Otherwise it’s a waste of time.

“Then I’ll shoot over and over again to make it interesting. What I do isn’t simple. It’s complicated and well-thought-out. Sometimes I think about a project for months.”

His painstaking approach was evident in a recent project that he terms “the most amped-up I’ve ever been,” a shot of a kayaker going down a 35-foot waterfall near Bend, Oregon.

“It took about six months,” he says. “First I had to track down the location, then wait for the optimum flow of water, then find the right talent and gear, then wait for the ideal lighting.

“Yet with all the prepping, I had just a tenth of a second when the kayaker was in the right position.”

The resulting shot shows the bright red boat about a third of the way down the falls. One bank of the river and the water itself are lit by the sun. The opposite bank lies in darkness.

“I was really nervous,” Saloutos says. “It seemed forever until he popped back up out of the water.”

Because much of his work is stock photography, it’s likely to be a year or more before he begins to see a return on his considerable outlay of time and money for that shot. Advertising agencies are among the leading purchasers of his work.

“That waterfall shot isn’t for a kayak company,” he explains. “It might appeal to a semi-conductor maker that’s positioning itself on the cutting edge of technology.

“My running shots are for anyone who’s emphasizing performance and individual sacrifice. A shot of a rowing crew might sell to an insurance company that’s emphasizing teamwork.”

The importance of ad agencies to his livelihood became even more apparent in the wake of Sept. 11.

“In past recessions, they cut back,” he says. “This time, they just stopped. There was also a big washout in ad agencies. All the marginal ones were toast. I’m represented in 60 countries, and they were all slammed.

“But I’m hopeful that we’re through the worst. There should be an acceleration as the economy picks up.”

While he waits for things to improve, Pete Saloutos takes an attitude that Randy Moss might not understand, but that resonates with the rest of us: “I’m just going about my business, shooting stuff.”